This past weekend, I was perusing the US Naval Institute website (probably one of my favorite websites), when I came across an article, “Unique Ships of the U.S. Navy.” Featured in the article were seafaring oddities like the world’s smallest nuclear sub, a concrete-hulled refrigerated barge used to supply sailors with ice cream in World War II, and the Navy’s “smallest aircraft carrier,” the USS Baylander, which is now a resident of Brooklyn Bridge Park.

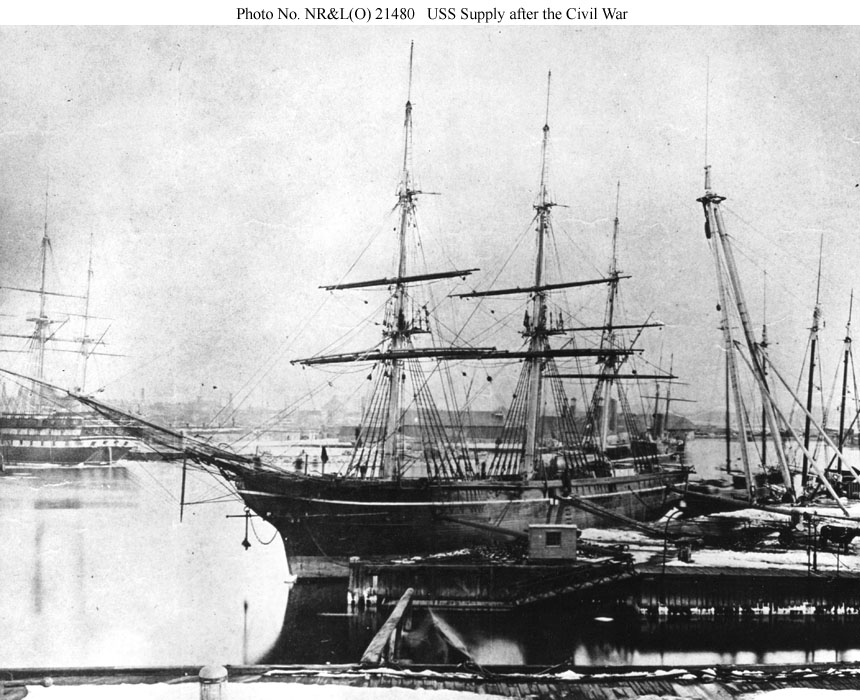

Another one of the vessels on this list caught my eye: the USS Supply, which in 1855–57 embarked on one of the most unusual journeys in American military history. Its mission was to travel to the Middle East to procure for the US Army an experimental caravan of camels to be used for military operations in the arid Southwest. The project itself was remarkable – and has been written about extensively – but it drew my attention because of its close connections to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The idea of bringing camels to North America had been floating around for a couple decades before it was taken up seriously by its most prominent advocate, Jefferson Davis. As a US senator from Mississippi and then as Secretary of War in the administration of President Franklin Pierce (and before becoming president of the Confederacy), he was a strong proponent of a southern-routed transcontinental railroad – and the expansion of slavery into these new territories – and he stumped hard for the Gadsden Purchase of what is today southern Arizona from Mexico in 1854. He raised the idea of importing camels for use in the Southwest in 1853, and by 1855, he had convinced Congress to apportion funds for their acquisition. The 1855 Army appropriations bill includes, “the sum of thirty thousand dollars be, and the same is hereby appropriated, to be expended under the direction of the War Department, in the purchase and importation of camels and dromedaries, to be employed for military purposes.”

But Jefferson Davis is not the hero of our story. That honor belongs instead to David Dixon Porter, one of the most accomplished and decorated sailors in the history of the US Navy. Porter was from an esteemed Navy family, son of Commodore David Porter, a hero of the War of 1812, and adoptive brother of David Glasgow Farragut (for their heroics in the Civil War, Farragut and the younger Porter would go on to become the first and second, respectively, admirals in the history of the Navy). But he did not get the commission based on his bloodlines; he had earned his first command in the Mexican War by mounting a daring raid at the Battle of Tabasco, and he had served in the Mediterranean Squadron, meaning he was familiar with the region. It also so happened that his brother-in-law, Gwinn Harris Heap, was an accomplished illustrator and naturalist who had lived in Tunis, making him a perfect companion for the journey.

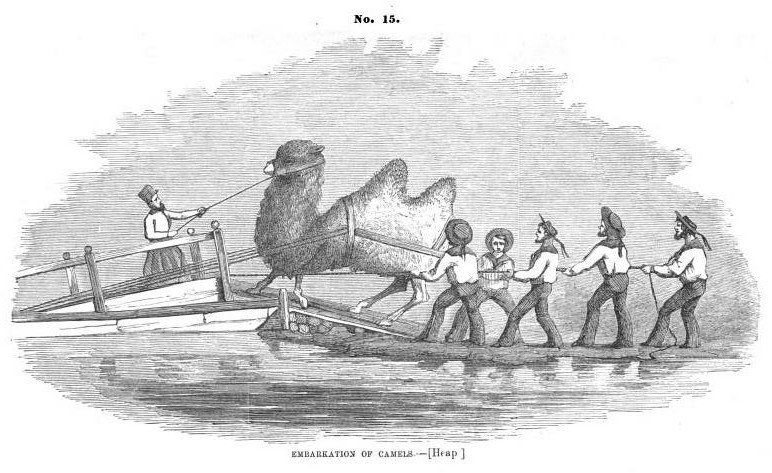

Their assignment was to procure a stock of camels and deliver them to Indianola, Texas, for deployment and experimentation by the Army. Porter arrived at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in May 1855 to make preparations and outfit and modify Supply for her unusual mission, which is described in detail in the 1857 expedition report from the War Department. A 60-foot-by-12-foot barn was built on top of the deck, and large hatches were cut to allow the lower decks to accommodate camels. He also had a special boat constructed to ferry the animals from shore to the ship, and a “camel car” – essentially a large wooden and iron crate – that could be used to hoist the animals from the ferry into the ship’s hold. This ingenious design was meant to avoid the very unpleasant task of tying these large and ornery animals into slings for hoisting, as was the custom with horses.

While it is extraordinary to contemplate the work that the shipwrights and carpenters at the Brooklyn Navy Yard did to get the ship ready for this mission, one of the things that struck me about this story is that in recent years, I have seen similar work being done at the Yard. For several months in the winter of 2012–13, the Falconia, a commercial cattle carrier, was berthed at the Yard while work was done on its engines by GMD Ship Repair. I do not believe that there were any camels aboard (or any animals at all), though in the photo below you can see hay clearly stacked on the forward deck.

The expedition departed on June 3, 1855, arriving first in La Spezia, Italy, where Porter met his Army counterpart, Maj. Henry C. Wayne. They traveled extensively around the Mediterranean searching for the most suitable camels. In Tunis, they bought a few just to test out their loading equipment, but Lt. Porter remarked, “So well satisfied am I with my experience with the Tunisian camel, that I would not hesitate to procure stock from that regency, being well satisfied that they will suit the climate of Texas.” In Crimea, they observed Allied forces using camels in the siege of Sevastopol, a fact that was driving up their price around the region. And in Egypt, camels nearly were the cause of an international incident when the Governor of Alexandria attempted to pass off sub-standard specimens as “gifts” to the US government, causing Porter to liken them to “rusty muskets or a rotten ship,” adding, “we will not accept any gift unless made in the proper manner,” as cited in this article from the December 1957 issue of US Naval Institute Proceedings magazine. Six quality dromedaries were quickly delivered by the Viceroy of Egypt.

In all they procured 33 camels – 30 of them dromedary (single-humped), and 3 bactrian and hybrid (double-humped) – for transport back to the US. Porter laid down strict and exacting rules for the care of the camels aboard the ship. They included, “The camels are to be fed and watered every day at three o’clock; the females having young ones to be fed and watered at seven o’clock in the morning besides”; “Each camel is to be curried and brushed half an hour every day and their legs and feet well rubbed”; “When the camels lie down at sea, particular care must be observed in putting hay under their knees and haunches”; and most importantly, “The least thing the matter with an animal must be reported to me at once by the person in charge, and no change whatever in the management of them to be made without my orders.”

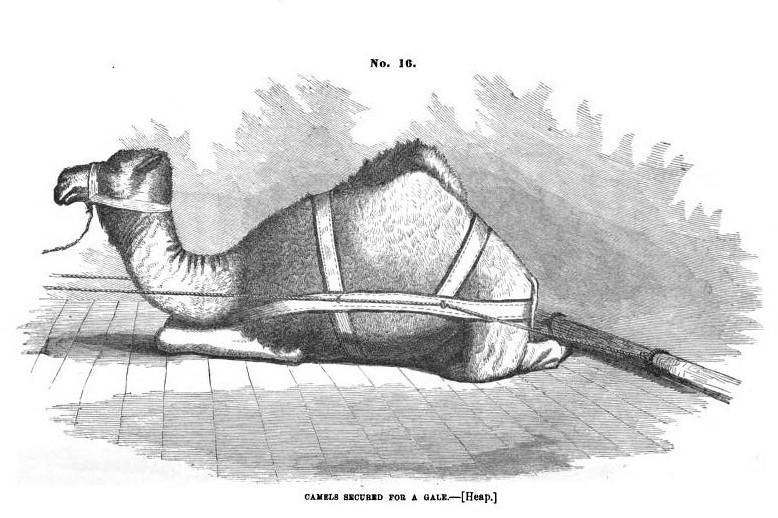

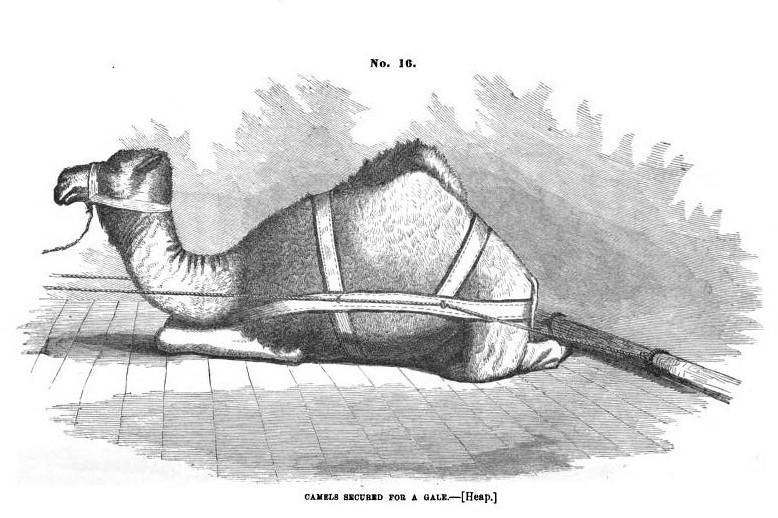

The camels fared remarkably well on their sea journey. The earliest purchases spent more than nine months confined aboard the ship, and even in the midst of a gale, “they bore the rolling admirably,” Porter reported. During bad weather, they did have to be secured, and he devised a system of tying them down on their knees below decks, illustrated below.

When they arrived in Texas on May 14, 1856, they had 34 camels – four had died en route, though another five were born at sea. While Wayne debarked with them to begin training soldiers on them, Porter received orders to return to the Mediterranean “to procure an additional number of camels for the military service of the United States.” Rather than comparison shop again, he and Heap proceeded directly to Smyrna, Turkey, where the bulk of the first group had been bought, and purchased 44 camels, 41 of which survived the return journey. This time, they also secured the services of eight professional camel handlers who returned to the US with them.

Over the course of their assignment, Porter and Wayne likely became the preeminent experts on camels in the United States. The 1857 report goes into exquisite detail about the biology, training, and care of the animals, including a daily “Camel Journal” of the feeding and condition of every animal. This was buttressed by the latest scientific research from Europe, Wayne’s reports of successful field tests, and even includes an appendix about the zembourek, or Persian camel-mounted artillery.

Despite these glowing reports, the camel corps were short-lived. As the New York Times explains, soldiers did not take to camels, nor did their horses and mules, and the eruption of the Civil War made camel cavalry a very low military priority. Many of the animals were sold off or slaughtered, with a few remaining descendants hanging on at ranches, circuses, and in the wild into the early 20th century.

Turnstile Tours offers several tours that highlight New York’s waterfront, past and present. We offer our Past, Present & Future Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard every weekend, and other special themed tours of the Yard. All tours are offered in partnership with and begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at Building 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the Yard’s history, and a host of great special events and programs.