We have experience hosting a range of audiences, from college classes to birthday parties to company outings, and we customize our tours to meet your group’s interests and needs.

Book a private tour today

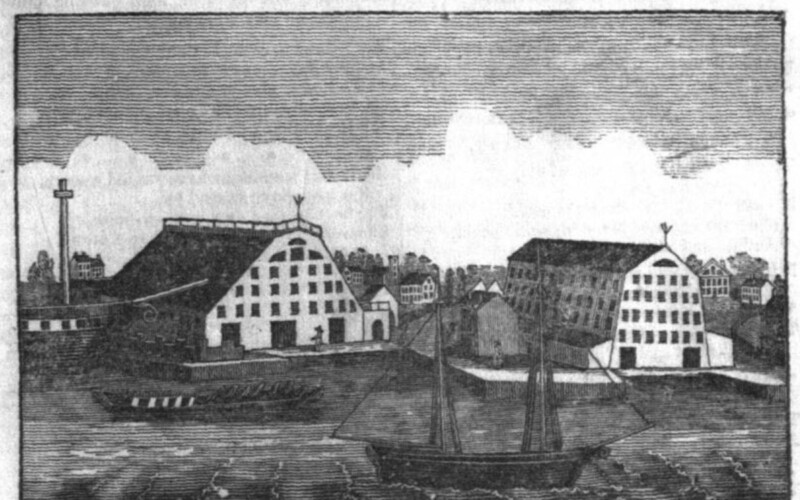

To celebrate the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s 221st birthday, which takes place during Black History Month, we’re looking at the past and present of Black trailblazers and innovators at the Yard. …

Read more

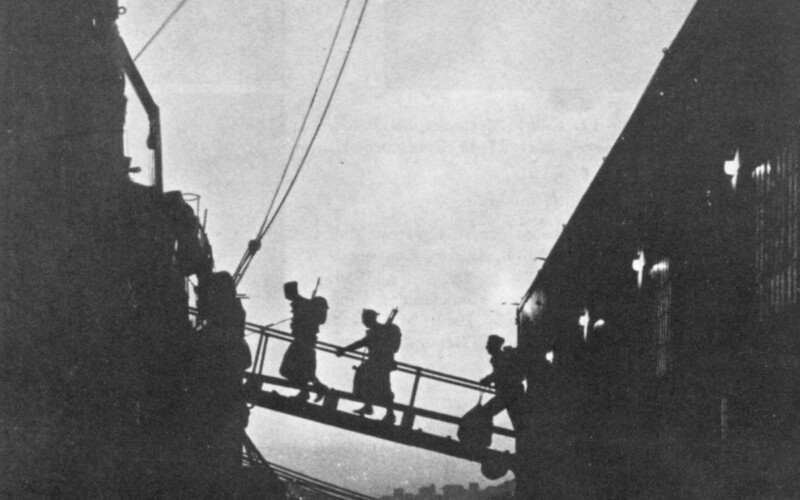

Celebrate Valentine’s Day as we share some of our favorite love stories from history from the places that we work. We will share long-distance love letters from World War II, …

Read more

The celebrate Black History Month and the 220th birthday at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, we are looking at the obstacles and opportunities that Black people encountered at the Brooklyn Navy …

Read more

After nearly 12 years of leading tours at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, one of the most difficult questions we get – and almost always from young people – is this: …

Read more

Last week we looked at Operation Magnet, the scramble in the weeks after Pearl Harbor to move American forces into the European battle zone. Just one week after that, it …

Read more

World War II came to a close in 1945, and looking back 75 years, it is hard to believe that Americans on the cusp of war in 1940 were as …

Read more

This summer marks the 70th anniversary of the tragic events of Port Chicago, California, the worst home front disaster of World War II. 320 people were killed, most of them US Navy sailors, …

Read more