Last week we looked at Operation Magnet, the scramble in the weeks after Pearl Harbor to move American forces into the European battle zone. Just one week after that, it was time to make a move in the Pacific, and the Brooklyn Army Terminal would again be key.

Unlike Europe, America already had significant forces in the Pacific theater, and they were engaged in battle with the Japanese – but it was going very poorly. The Japanese began their invasion of the Philippines just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and within a month, American forces were penned in on the Bataan Peninsula and the island fortress of Corregidor, and the American Asiatic Fleet, along with Dutch and Commonwealth allies, was being battered across the Southwest Pacific. By May, 87,000 American and Filipino troops would be forced to surrender, and half the Asiatic Fleet was sunk.

But the Allies had a plan, sort of. As early as 1939, the Americans and British had discussed occupying islands that could block the Japanese from moving against Australia and New Zealand, including Tonga, Fiji, and the French colony of New Caledonia. After the fall of France, the island’s government declared their loyalty to the Vichy puppet regime, but this was quickly replaced by a Free French administration. After lengthy negotiations, they agreed to allow American forces to occupy the island and build bases. Now they just had to get them there.

At the same time, the Army was undergoing a major reorganization that complicated matters. Previously, divisions were “square,” meaning each consisted of four regiments; instead, they would become “triangle” divisions, of only three, leaving a lot of “surplus” regiments without a division assignment. Though there was no full division yet ready to go into combat, there were plenty of pieces – and these were swept up to form Task Force 6814, assigned to take New Caledonia. Not yet a formal division, two of its main components were the 182nd Regiment, detached from the famed 23rd “Yankee” Infantry Division, and the 132nd, once part of the 33rd Infantry Division (its third regiment, the 164th, was the corner removed from the 34th “Red Bull” Division before they shipped off to Belfast, but they would not depart for the Pacific until March).

The plan to pull together these regiments, along with many other smaller units, was only finalized on January 14. Soldiers had to be brought to New York from over a dozen different states, including Massachusetts, North Carolina, Alabama, and Texas. While the San Francisco Port of Embarkation may have been a more logical choice for a Pacific operation, the proximity of units, equipment, and ships, as well as the capacity of the port, made New York the only option. Some units were moved to the staging area at Indiantown Gap, PA awaiting transport, but there wasn’t enough space for all of them; the 810th Engineer Battalion, an all-black unit (along with the 811th, these would be the first black troops deployed in the war), was forced to bivouac aboard the transport USS America while it was being worked on at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

This operation would be much larger than Magnet, which moved only 4,000 troops in its first component. But there wasn’t time to move this unit pieces; the French were growing impatient with American inaction, unaware that the top-secret operation was even underway, and they feared the Japanese were preparing to invade. So nearly 17,000 troops, along with their equipment, had to be loaded as quickly as possible, and it did not all go smoothly. Cargo was loaded haphazardly and often separately from the units that needed it. One artillery battalion feared that they had left without any actual artillery, only to discover upon arrival that it had been loaded onto a different ship. Partly as a result of this disorganization, and partly out of fear that the Japanese could capture New Caledonia before the got there, it was decided to make a pit stop in Melbourne, Australia to reorganize rather than head straight to the target.

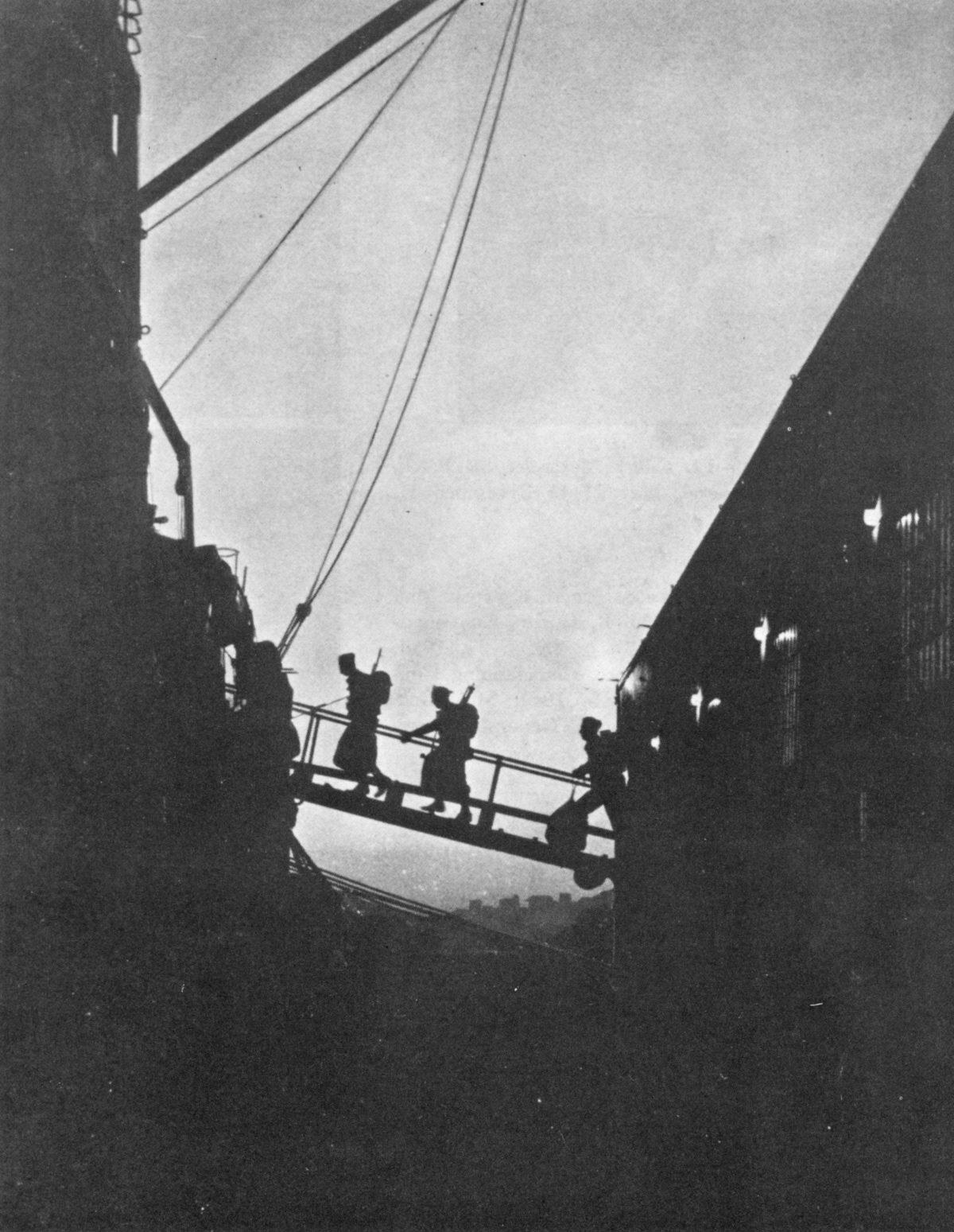

Seven transports – nearly all the available troopships on the east coast – had to be hastily assembled, the largest being the converted passenger liner USS Argentina, which was joined by Cristobal, JW McAndrew, John Ericsson, Santa Elena, Santa Rosa, and Thomas H. Barry. While most were loaded at the Brooklyn Army Terminal, some took on troops at Pier 90 on Manhattan’s West Side. Loading started on January 19 and would take four days to complete. Some troops boarded their transports this early and were stuck in port for up to three days, while others did not embark until late in the day on January 22. Finally, convoy BT.200 got underway well after midnight on January 23.

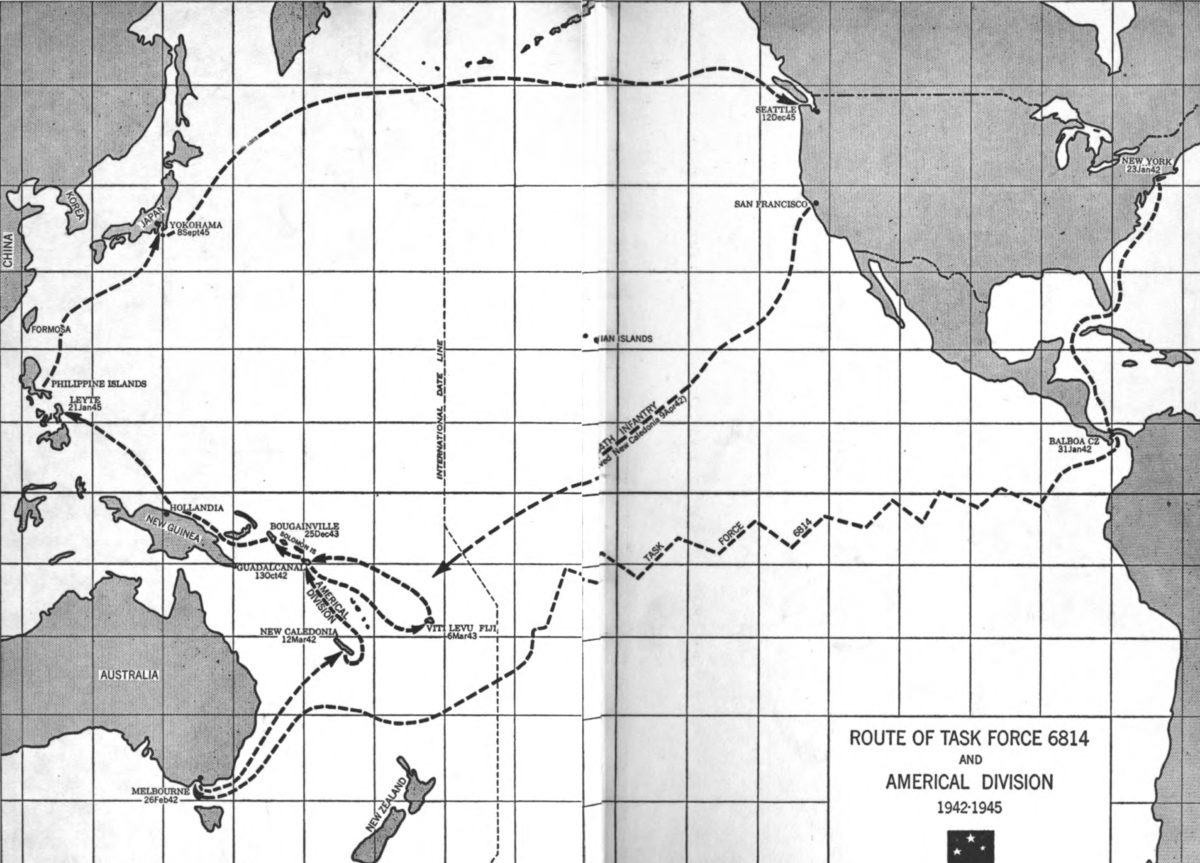

The journey was long, but largely uneventful. Though German submarines were prowling the Atlantic coast, only one unconfirmed U-boat contact was made, and the convoy arrived safely in Panama on January 31 for a brief stopover. Several newsletters were published aboard the ships during the journey, including the Twin-Ocean Gazette on Argentina, and being aboard a former cruise liner did provide certain perks, such as a still-functioning swimming pool on the top deck, where they celebrated the crossing of the Equator with ceremony for King Neptune. But the five-week journey was tedious, and the facilities were sorely lacking. By the end of the voyage, soldiers were limited to just one canteen of fresh water per day, with no water for showers, and dysentery had broken out. Melbourne was a welcome sight when they arrived on February 26, after 35 days at sea.

But the journey was not over yet. After a week of rest and reloading in Australia, the convoy was underway again for the six-day journey to Noumea, New Caledonia, where they arrived on March 12, 48 days after leaving New York. Now they could get to work building bases and airfields. But the division still did not have a name, jumbled assemblage of units. After its third infantry regiment, the 164th, arrived in April, the division was finally at its full complement, and it was christened “Americal” (AMERIcans in New CALedonia), formally activated as the 23rd Infantry Division on May 27 and adopting the Southern Cross constellation as its insignia.

While New Caledonia was not a battlefield, it would not be long before Americal was sent to the front lines. In August, the Navy and Marines invaded Guadalcanal, a key island in the Solomon chain, and the 23rd Division would reinforce them in October, remaining mired in the bloody struggle until March.

In these weeks following Pearl Harbor, the US Army was small and disorganized, the Navy outgunned and undermanned, and both lacked the ships and sailors to effectively move forces into the fight far from American shores. The New York Port of Embarkation was not the well-oiled operation that it would soon become. Yet somehow, Task Force 6814 made it across two oceans and was pieced together into a coherent fighting force, one that became highlight decorated fighting across the Southwest Pacific until the close of the war.