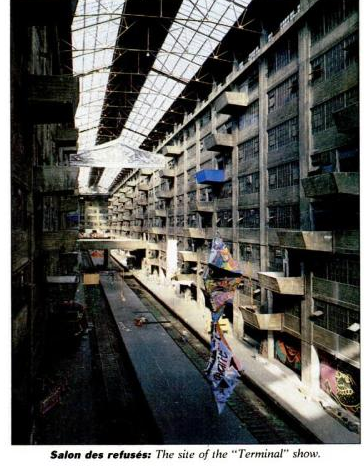

It was supposed to rival the Armory Show, billed as “potentially the most controversial and innovative exhibition” since that groundbreaking moment in 1913. Thirty years ago this month, “Terminal New York” opened, and 400 artists filled the abandoned space of the Brooklyn Army Terminal with a vast and riotous display of art that could hardly be contained even by the terminal’s cavernous spaces.

The show was originally conceived by Carol Waag, an artist and graphic designer for the New York City Public Development Corporation (which has since evolved into the New York City Economic Development Corporation, who now manages the site). Built in 1918–19 as an army supply base, the military decommissioned it in 1966, and it had sat idle since 1975, when the few remaining federal government tenants left. The City of New York bought the property in 1981, but two years later, it still lay empty and unused. Once Waag floated the idea of the show, the PDC quickly agreed, considering it a perfect way to showcase a space they hoped to renovate and redevelop as new industrial space.

Wagg enlisted two other artists, Barbara Gary and Rhonda Zwillinger, and writer and art critic Ted Castle, to help with the organizing. Six hundred artists answered the call for proposals, a number that was then narrowed down to about 200, and some 200 more were specially invited to participate. According to Castle, quoted in the New York Times, the purpose of the show was to accumulate “‘a considerable sample of freshly produced art of almost all kinds,’ which would give viewers ‘a revelation not only about art now but also about the state of the world out of which this art arises.'”

“Terminal New York” centered around the eight-story atrium inside Building B of the complex, a space previously used to move army supplies from trains that ran through the building into the massive warehouses. Art hung from the balconies, on the walls, and spread throughout the ground floor of the space. Taking inspiration from its past uses, war (and Cold War-era paranoia) themes were present in much of the artwork, as in Dave Channon’s giant skeleton figure hung in the atrium.

Some loved the show—New York magazine’s Kay Larson noted, “This is what the art world looks like before it is weeded, seeded, and preened by ambitious New York curators”—while others were less impressed. “The overwhelming number of objects that vie for attention is enough to glaze the eyes—and blister the feet—of the most avid art adventurer,” art critic Grace Glueck wrote in the Times.

In fact, she felt one of the biggest downfalls of the show was that the space itself, particularly the skylit atrium, was far more interesting to look at than the art inside it. Many artists tried to work with the space, including multiple pieces hanging from the ceiling, and one that incorporated the railroad tracks running through the building, Tim Watkins’ “The Train Doesn’t Run Here Anymore,” with planted grass growing between the tracks (something that, with the atrium glass removed, happens naturally these days). Other pieces played with the shadows of the space and interplay between the bright, open atrium and the dark warehouse spaces, like Daniel G. Hill’s “Zoopraxiscope.”

But for Larson, there was a sense of urgency in the exhibition and of the artists involved to be seen. She thought that feeling was exemplified by a particular piece of art painted in red on one of the walls by artist Laura Foreman:

I have

nothing

to paint and

I’m

painting it.

Today, artists continue to be an important part of the Brooklyn Army Terminal’s reinvention. The complex houses roughly 50,000 square feet of space leased by ChaShaMa, a non-profit organization that offers subsidized studios for artists, which has been in the Terminal since 2005. ChaShaMa recently held their annual BAT open studios, once again opening up the space to the public as an exhibition hall to showcase the work of their 90+ artists in residence (these spaces will not open again until next year, but you can visit ChaShaMa’s Harlem space on October 12 & 13, or visit the BAT atrium during Open House New York on October 12). Art from ChaShaMa is regularly displayed at the Terminal—on now until until December 20, the lobby of Building B houses “Three Years at BAT,” a show of paper collages and posters by Jonathan Fischer, a current BAT ChaShaMa artist.

“Terminal New York” didn’t turn out to be the 1980’s version of the Armory Show. But it did help to unlock some of the incredible creative potential of this abandoned military space. A few remnants of the show can still be found: a scrap of graffiti – “Art Guerra [War]” – from an unknown artist remains on a column on the southeastern side of the atrium, largely unnoticed alongside the similarly fading Army-era signage it was likely meant to critique.

Editor’s Note: Subsequent to publishing this article, several visitors pointed out to us that this small mural is not a reference to the subject matter of the show, but the signature of an artist. Art Guerra was a painter, muralist, and perhaps most famously, a well-known supplier of quality paints to artists. He had a piece in the Terminal New York show inside the atrium, though we have yet to track down an image of the work. Three years after the show, he opened his shop, Guerra Paint & Pigment, on 13th Street in the East Village. Guerra passed away in 2021 at the age of 81, but his business partners Jody Bretnall and Seren Morey continue his eponymous business. The 13th Street store closed in 2022, but they still operate out of their facility in Maspeth, Queens.