Last month, we were so excited to learn that the Brooklyn Navy Yard has been added to the National Register of Historic Places. But this raises an important question: what on earth does this mean, exactly?

Historic preservation often involves a complicated maze of local, state, and federal legal requirements, so we thought we would explain what the National Register is, what the benefits are, and what impact this will have on the Brooklyn Navy Yard. To get a better understanding of the National Register and its implications for the Yard, we spoke to Shani Leibowitz, Senior Vice President of Development and Planning at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, who was a tremendous help.

So, here’s our explainer:

Why is the Brooklyn Navy Yard an historic place?

First, a bit of background. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was established in 1801 as a federally-owned and operated naval shipbuilding and ship repair facility. Over its history, more than 100 naval vessels were built there, and tens of thousands were repaired, outfitted, and commissioned at the Yard – at its peak production during World War II, it employed more than 70,000 workers, and more than 5,000 ships visited the facility in just four years.

In 1966, the US Navy decommissioned the Yard, and most of the property was sold to the City of New York in 1969 for $22.5 million. Since then, the Yard has been operated as an industrial park, and since 1981, the property has been under the management of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, a non-profit organization. Several parcels of the historic Navy Yard property remained in federal hands after 1969, including the Admirals Row site on Flushing Ave (acquired by the city in 2012), the Naval Hospital Campus (acquired by the city in 2000), and the Commandant’s House (sold by the federal government to a private buyer in 1979).

Today, the Yard is home to roughly 330 tenants that occupy about 40 buildings – both repurposed structures from the Navy days, as well as new construction – and 7,000 people come to work at the Yard every day. There are currently no naval or other military activities of any kind on the site, though there is still an active commercial ship repair yard.

What is the National Register of Historic Places?

The National Register of Historic Places is administered by the National Park Service, under the federal Department of the Interior. Established in 1966 under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), the purpose of the Register is to “coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America’s historic and archeological resources.” Additionally, the act also created State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPO), which are responsible for coordinating listing efforts in each state.

There are more than 90,000 individually-listed sites on the Register, and more than one million structures, as many of the listings are of historic districts that encompass several properties, of which the Brooklyn Navy Yard is now an example (individual structures within a district are known as “contributing resources.”) Each year, roughly 30,000 structures and properties are added to the National Register. As of 2012, there were 897 listed sites in New York City, and 160 in Brooklyn alone, including the Cyclone roller coaster, Green-Wood Cemetery, and, for some reason, all of Ocean Parkway from Church Ave to Coney Island.

How does a site get listed on the National Register?

In order to be listed, a site must first be nominated. The nomination can be proposed or prepared by public or private entities or individuals, but it is reviewed by the relevant SHPO, which then submits the official nomination to the National Park Service. The nomination process is rarely easy or short, as it requires meeting specific criteria about the historical, architectural, and/or archeological significance of the site, and submitting exhaustive evidence to support those claims.

For the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the New York SHPO submitted its nomination back in 2012, noting that the Yard is “historically and architecturally significant as a collection of nineteenth and twentieth century industrial, residential and institutional resources associated with the establishment and development of one of the nation’s oldest naval installations,” Leibowitz said.

So, is the Brooklyn Navy Yard now a “landmark”?

No, this listing does not make the Brooklyn Navy Yard a New York City Landmark Historic District, which is a city-level designation that carries with it an entirely different set of requirements as laid out by the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission. Nor does it make it a National Historic Landmark, a program that is part of the National Register, but with more stringent requirements for inclusion (there are only about 2,500 in the whole country).

The Brooklyn Navy Yard is, however, already home to three New York City Landmark structures – Dry Dock #1, the Brooklyn Naval Hospital, and the Surgeon’s House – which have garnered special protections of their exterior appearance. The Commandant’s House, also known as Quarters A, located in the Vinegar Hill neighborhood adjacent to the Yard, is simultaneously a New York City Landmark (since 1965), a National Historic Landmark, and on the National Register (both since 1974), but it is no longer part of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Completed in 1807 as the first purpose-built structure at the Navy Yard, the property was sold by the Navy to a private buyer in 1979.

What are the benefits to being listed on the National Register?

The major benefit for listing on the National Register is that buildings can be eligible for state and federal Historic Preservation Tax Credits. These credits can be used to support and finance renovation of historic buildings, provided those renovations meet specific standards. If met, the federal credits are worth 20% of qualified renovation costs, meaning a renovation with $1 million in qualified costs would receive a $200,000 credit on federal taxes. Similarly, New York State provides a 20% credit on state taxes, with a limit of $5 million in credit (meaning up to $25 million in qualified costs are eligible). As a result of the listing, renovation projects within the Brooklyn Navy Yard can be eligible for these credits.

The standards for these tax credits can be quite exacting and difficult to meet. Called the Secretary’s Standards for Rehabilitation, they include such requirements like, “A property shall be used for its historic purpose or be placed in a new use that requires minimal change to the defining characteristics of the building and its site and environment,” and “surface cleaning of structures, if appropriate, shall be undertaken using the gentlest means possible.” Often the demands include using original materials or building techniques that are impractical, cost prohibitive, or simply not available anymore.

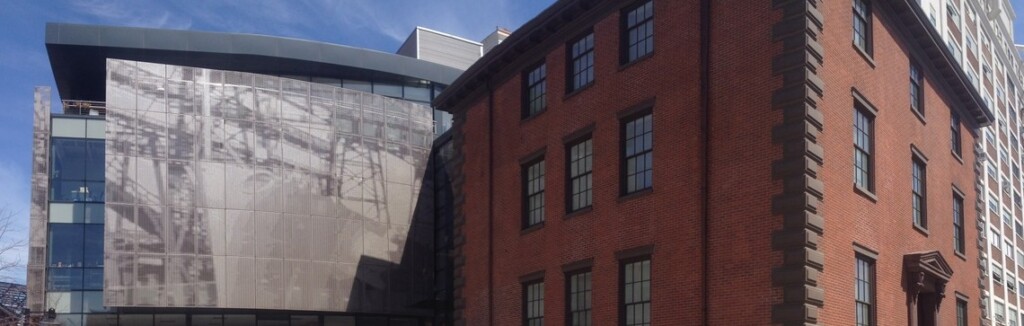

Leibowitz noted, “BNYDC has continually preserved many of the resources in the Yard to reuse them for their original manufacturing purpose,” which would help to meet this first criteria. However, she added, some beautiful renovations done before the Yard was nominated for the Register, such as the Marine Commandant’s Residence (now home to the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, the Yard’s visitor and exhibition center) and the Paymaster Building (which houses Kings County Distillery), would not meet the Secretary’s standards, for various reasons, and would not be eligible for these tax credits.

The largest project currently underway for which the BNYDC is seeking Historic Preservation Tax Credits is Building 128, a 220,000-square-foot former engine fabrication shop. While the exterior will be restored to its original appearance, the interior will be transformed into the Green Manufacturing Center, which will house modern design and manufacturing facilities. Two existing Yard tenants, Crye Precision and New Lab, have already announced plans to move into the larger space once it is completed.

Ultimately, the mission of the Brooklyn Navy Yard is to provide jobs for New Yorkers by upgrading and improving the site. This listing will provide more opportunities to finance those improvements while still maintaining its high-quality industrial spaces and historic character.

Does this listing place any restrictions on the development of the Brooklyn Navy Yard?

Not really. The National Register is more of incentive program than a set of restrictions, and listed private properties can still be altered or even demolished. The Register does, however, place restrictions on the activities of the federal government and the use of federal dollars on historic sites, which does affect the Yard.

Section 106 of the NHPA requires that whenever the federal government engages in any activity that may affect a property listed on the National Register, that project must undergo a so-called “Section 106 review” of its impacts. Therefore, whenever the Brooklyn Navy Yard seeks state or federal funding, those projects must undergo Section 106 review by SHPO, as well as a review under the parallel state law (called Section 14.09). However, this review requirement actually kicked in the moment the Yard was nominated by SHPO back in 2012, as “eligible” and “listed” sites face the same requirements, so there are really no new requirements or restrictions that the listing places on the Yard.

“The listing does not restrict the design or reuse of buildings for which [state and federal] tax credits are not being sought,” Leibowitz said.

Turnstile Tours offers the Past, Present & Future Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Saturday and Sunday afternoons, and other special themed tours of the Yard by bus and bicycle select weekends. All tours are offered in partnership with and begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at Building 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the Yard’s history, the Ted & Honey rooftop café, and a host of great special events and programs.

This post was authored by Andrew Gustafson.