Two hundred and thirteen years ago today, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was founded, the last of the six original shipyards established by the US Navy. Today we celebrate the yard’s history of shipbuilding and innovation, and its continued importance to the economy of Brooklyn as an industrial park, but it almost never existed. Its founding in 1801 was rife with controversy, and around it swirled one of the central political battles of the early American republic. Today the Navy is one of the cornerstones of American power – possessing 10 of the world’s 11 nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and more than one-third of all the naval tonnage in the world, the US Navy is 3.5 times the size of its nearest competitors, China and Russia. But at the end of the 18th century, the American navy was small and, at times, a non-existent force. While it achieved some notable victories in the Revolutionary War over a far superior British adversary, by 1785, economic constraints forced the nascent republic to sell off the last of its warships.

The naval question was a contentious political issue. In 1787 in Federalist Papers No. 24, Alexander Hamilton, writing under a pseudonym, implored the young nation to restore its vanished navy: “If we mean to be a commercial people or even to be secure on our Atlantic side, we must endeavour as soon as possible to have a navy. To this purpose there must be dock-yards and arsenals; and, for the defence of these, fortifications and probably garrisons.”[1]

During George Washington’s administration, American politics settled into two rival factions – the Federalists, led by John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, and the Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson. Their disagreements rested on fundamentally different beliefs about foreign affairs, economic policy, and the role and scope of federal power. The Federalists believed in maintaining a standing military, especially a strong navy, while the Republicans were opposed to establishing a permanent force, with the exception of maintaining coastal defenses. With American shipping increasingly falling prey to foreign navies and pirates, in 1794 Congress apportioned funds[2] for the building of six frigates (one of which is still a commissioned vessel of the US Navy, the USS Constitution) that would become the cornerstone of the early Navy. These vessels would arrive just in time, as in 1798, the Quasi War with France erupted, sparked by the growing ties between the Federalist administration of John Adams and Great Britain, as well as by Adams’ refusal to pay America’s debts to France incurred during the Revolutionary War. The Federalists believed that the debt was owed to the French crown, which had been toppled in 1789, meaning they owed nothing to France’s revolutionary government. To exact repayment, French naval ships began attacking the American merchant fleet around the world.

Adams was in favor of a strong military, and as part of this effort to beef up the Navy, the office of Secretary of the Navy was created in 1798.[3] The man Adams appointed to build this force was Benjamin Stoddert. Born in Maryland, Stoddert was a veteran of the Continental Army and ran a merchant shipping business in Georgetown. He found the Navy’s affairs in disarray when he arrived at his post in June 1798, but he was a shrewd businessman who set about organizing operations and cutting waste and fraud. At the time, all naval ships were built by private contractors, who often over-billed the government for their work. Stoddert and his staff drove hard bargains with shipbuilders and attempted, with limited success, to standardize naval procurement and building practices.[4] Stoddert believed that one of the most wasteful practices of the Navy was purchasing timber for ships without any proper place to store it. Timber had to be moved from one private shipyard to another, and often the spaces were too confined for the construction of such large ships, resulting in major delays and cost overruns caused simply by having to constantly stack and sort the timber. While Congress had appropriated money for the building of docks and wharves, as well as for the wood itself, these improvements were made to private property, accruing little or no long-term value to the public.[5]

On April 25, 1800, Stoddert wrote a letter to President Adams with a potential solution to the problem. While Congress’ 1799 naval acts[7] had only appropriated funds for the construction of two ship docks and the purchase of timber, they did not expressly prohibit using those funds for something else – namely, the purchase of land to establish permanent federal navy yards. He wrote:

In this view of the subject, and believing that it is the truest economy to provide at once permanent yards, which shall be the public property, and which will always be worth to the public the money expended thereon, instead of pursuing the system at first adopted, which, with the experience before us, can only be justified on the ground that the ships, now ordered, are the last to be built by the United States, the Secretary of the Navy has had but little difficulty in making up his opinion that the proper course to be pursued is, to make the building yards at Norfolk, Washington, New York, and Portsmouth, public property, and to commence them on a scale as if they were meant to be permanent. And also, the building yards at Philadelphia and at Boston, notwithstanding the high prices which must be given for the ground.[6]

Even before he drafted this letter, Stoddert had been working on this plan – in March, he purchased a stretch of land in Washington, DC, one that had already been set aside for federal use, to create the Washington Navy Yard.[8] And back in January 1800, he had directed his chief naval constructor Joshua Humphries to begin surveying the coast of New England for suitable sites for navy yards.[9] The next plot purchased, on June 12, 1800, was along the Piscataqua River between New Hampshire and Maine, which would become the site of the Portsmouth Navy Yard – a bargain at just $5,500. Three days later, Stoddert’s agents completed the purchase of the Gosport Navy Yard in Norfolk, Virgina, which the federal government had already been leasing for shipbuilding, for $12,000. Next, they set their sights on Boston, where by August they had bought up ten adjacent plots of land in the Charlestown area for a total of more than $37,000.[10]

During this time, Adams found himself in the midst of a vicious re-election battle, one he would ultimately lose to Jefferson, in large measure due to his unpopular foreign entanglements, his support of a standing military, and his attempts to squelch political opposition with the outrageous Alien and Sedition Acts. Yet even after the election was lost, Stoddert kept up with the task at hand. His lame duck administration signed the papers for the Philadelphia Navy Yard on January 20, 1801, and they completed a purchase for 23 acres of property on the banks of the East River on Long Island for $40,000 on February 23 – today the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.[11] The seller of the land was a man named John Jackson, a real estate developer and shipbuilder. On the site there already was a shipyard which Jackson operated – he had been a contractor for the Navy, building the USS Adams, a 28-gun frigate, in 1799. While he sold off a parcel to the Navy, he kept most of his holdings in Brooklyn, developing it into a residential and industrial district known as Vinegar Hill.

The purchase was completed just nine days before Jefferson assumed the presidency, and he would arrive in office surprised to discover that he was now the steward of six navy yards. As any student of American history will recall, Adams was quite busy during his final days as president, making his famous “midnight appointments” and sparking the groundbreaking Marbury v. Madison decision. Before the era of presidential “transition teams,” you can imagine Jefferson had quite a lot to handle in his early days. The first to bring the navy yard issue to the new president’s attention was Albert Gallatin, a Pennsylvania congressman who had been one of the most vociferous opponents of military spending. He wrote to Jefferson on March 14, 1801, ten days into the new administration:

The subject of the purchase of the navy yards seems to require attention. Is that at N. York completed? and if the appropriation does not cover the purchases, is there no remedy against the agents? … Under colour of that appropriation, it appears that at least 186,800 dollars have been applied to navy yards & the balance to frames for two additional 74s [74-gun ships of the line]. Mr. Stoddart in his report misquotes the word of the law & calls it an appropn. for preparing proper places for securing the timber.[12]

Stephen Sayre, a naval inspector on Stoddert’s staff – he was actually fired over his opposition to the purchase of the Brooklyn site – and a close ally of Jefferson, wrote to the new president on March 21:

I have been lately in New York, & think it my duty to inform you—that there has been a purchase of 10 acres [sic] of land, on Long Island, made by the agent, acting for the navy, at the enormous price of 40000. dollars. This agreement was the subject of conversation, & astonishment, in all companies, & of all parties—universally declaring, that, any private person might have bought it, for one fourth of the amount. If not too late, you will, of course not only investigate, but set aside this shameful transaction.[13]

Jefferson’s reaction to this letter was to write to Maryland Congressman Samuel Smith, whom he had tried to appoint as his Secretary of the Navy, but Smith declined; on April 17, he wrote, “I inclose you a letter from mr Sayre, stating a purchase in Long island of very ill aspect. if we have any power over it, suspend it.”[14] Smith’s reply was outrage at the seemingly illegal actions of the former naval secretary, but he was somewhat at a loss for what to do about it. He wrote on June 13:

Not being able to find that there was any Law authorising the purchase of Ground for Navy yards—I enquired and am informed that the purchase was understood to be authorised by the following Laws [1799 Naval Acts] … Being uncertain on this subject and being constantly pressed by other objects, I have declined giving any direction for improvements in any of the Navy yards, except that in Washington, where necessity has compelled me to order the building a Brick Warehouse for the reception and Safe keeping of the stores brought here and transporting from Baltimore. The work heretofore ordered on that yard as well as that of Portsmouth, it is presumed has continued to progress— It appears from the best information that I have been able to procure that the Navy yards in Philadelphia & Newyork are improperly placed—That at Phila. would have been better, had the ground been selected in the Northern Liberties, where such Docks could have been filled from the Globe Mill—That at Newyork being fixed on Long Island, not more than 8 Miles from the Sea is open to an attack from an Enemy, who might by landing 200 Marines in one night burn the ships & buildings—Kipp’s Bay is thought to be preferable—[15]

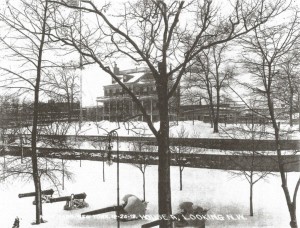

Ultimately, the Jefferson administration followed Smith’s advice, at least in relation to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, by dragging their feet. No purpose-built structures were begun until 1805, when ground was broken on the still-standing Commandant’s House. Not until the War of 1812 did the yard see concentrated activity, but even then it was primarily converting merchant vessels into navy ships; the first ship built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard was not laid down until 1817, the 74-gun USS Ohio, launched in 1820.

Stoddert did not win many friends with his hard-driving ways and his questionable interpretations of Congress’ wishes. But ultimately he left the Navy better than he found it – when he assumed his post, the US Navy had just 12 ships and 59 officers; when he left, it boasted nearly 50 ships, commanded by 700 officers.[16] Not only that, but by establishing the navy yards, it ensured the long-term future of the force, as these six yards would be critical centers of naval innovation through the Second World War. Today, three of the six yards remain active naval facilities – both Portsmouth and Norfolk are used for naval ship repair, and Washington houses support facilities – while the other three have been converted into industrial parks. At the Brooklyn Navy Yard, they still repair commercial ships, continuing the legacy stretching back to the Jackson Brothers shipyard, but the site is also home to more than 300 businesses employing 7,000 people – who knows what would be there today if Stoddert’s scheme hadn’t panned out?

[snippet slug=‘bny-footer’]

Footnotes:

[4] Toll, Ian W. Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2006. 105-7.

[6] Powell, Wilbur, ed. Control of Federal Expenditures: A Documentary History, 1775-1892. Washington: The Brookings Institution, 1939. 192-4.

[11] Brooklyn Eagle Almanac, 1922. 311.

[16] Toll, 106.