Update, February 20, 2024: Sadly, we lost Salty earlier this year, but she will forever live on in our hearts.

Last month, we at Turnstile Tours had the pleasure of adding a new member to our team – Salty. She is an Australian Cattle Dog mix (we think), and we adopted her from our nearby shelter, Sean Casey Animal Rescue in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn.

Little is known about her past life (she is about two years old), and she did not respond to the name given to her in the shelter, so we decided to giver her a new name to go with her new home. As is our want, we decided to find a name that would both fit her personality but also have some local historical significance.

The first place I looked for a namesake dog: the archive of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Shipworker newspaper at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92. The armed forces have a long and proud tradition of dogs in service (check out Rebecca Frankel’s blog and book War Dogs, and listen to a great This American Life story about the Army’s “Dogs for Defense” program in World War II), so we thought we would find a suitable Navy role model for our new dog.

At first we considered naming her after the mascot of the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built USS Iowa, Victory, or Vicky for short, but our dog didn’t seem to have the personality of a Vicky, who was a small, rather rambunctious animal. At least that’s what her personnel record suggests, as it included several reprimands and even a two-grade demotion (from Mascot First Class, M1C, to Third Class, M3C) for being AWOL and fighting.

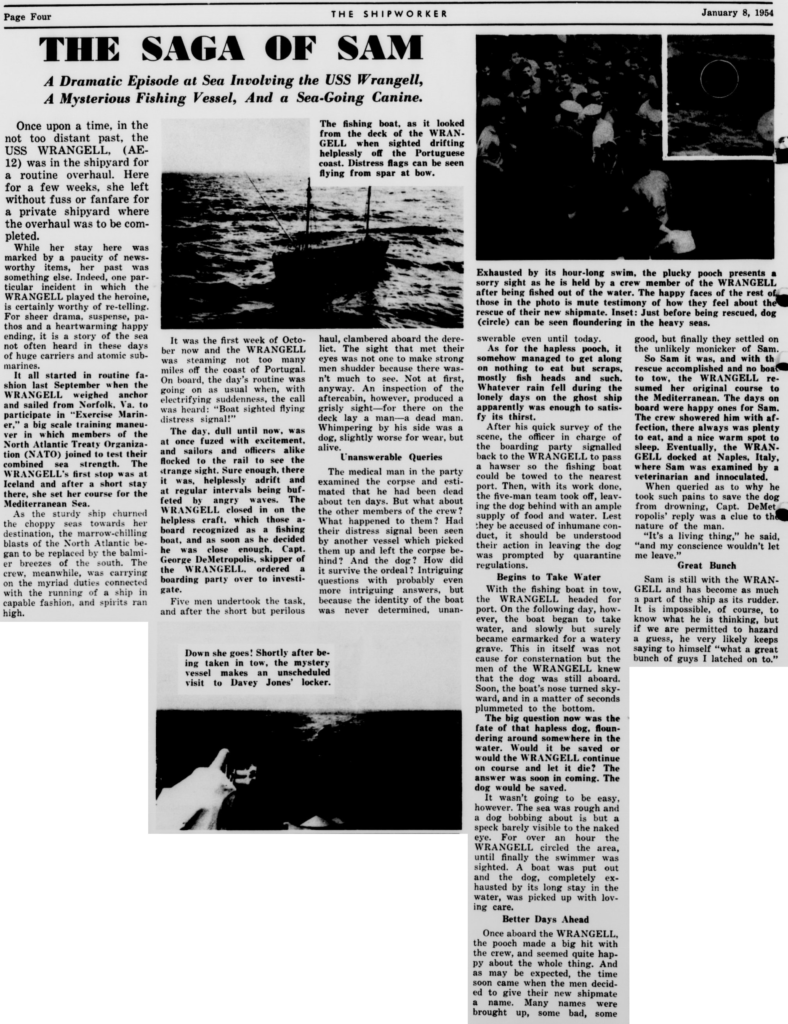

Then I came across an article about an incident that took place in October 1953 involving the USS Wrangell, an ammunition transport (AE-12). “The Saga of Sam,” published in January 1954 in the Shipworker described an eerie scene off the coast of Portugal. The Wrangell, en route from Norfolk, VA to the Mediterranean for an exercise, encountered a stricken fishing vessel adrift in rough seas in the North Atlantic. With a distress signal flying from the strange ship, Wrangell sent a boarding party to investigate. Once on board, they found only a single crew member, dead about 10 days, they estimated, and a starving, shivering dog, still alive.

The Shipworker described the animal, “it somehow managed to get along on nothing to eat but scraps, mostly fish heads and such. Whatever rain fell during the lonely days on the ghost ship apparently was enough to satisfy its thirst.” Unable to bring the dog or the fisherman’s body aboard due to quarantine regulations, the boarding party left food and water for the dog, and the Wrangell took the boat under tow.

While investigating more about this incident and the dog, I contacted the AE/AOE Sailors Association, an alumni group for men who served aboard these transports, including the Wrangell. The site’s administrator, Jerry King, was able to put me in touch with a few members who remembered that October day.

Robert Miller, who served aboard the Wrangell as a navigator, described the scene: “We attached a line to the mast and took the vessel in tow with reduced speed of 8 knots or less. During the next days the weather and seas turned rough and the vessel broke apart and sank.” Once the ship sank, Wrangell’s skipper George DeMetropolis ordered a change of course and began searching the area for any sign of the dog. After more than hour of searching, he was finally spotted. “The dog was seen floundering about, so we lowered a boat, and Ensign Frosell rescued the dog and brought him aboard,” Miller added. Win Perry, a hospital corpsman on the Wrangell, recalled that “[we] lowered a Stokes litter over the side and the dog climbed into it until they could retrieve the dog into the whale boat.”

After much deliberation by the crew, the dog was dubbed “Sam” and adopted as the ship’s official mascot. The story became a minor sensation, appearing in papers across the country. Many articles referred to him as “Salty Sam,” a moniker earned perhaps because he was now in the US Navy (a “salty dog”). Miller noted, “Don’t honestly remember if we called him Salty or Sam, but I think Salty most likely was his initial name because he was in the sea for about an hour or more before we rescued him, and of course he was very ‘salty’ when brought aboard!”

When asked why he decided to change course and look for the dog, Capt. DeMetropolis told the Shipworker, “It’s a living thing, and my conscience wouldn’t let me leave.” The paper concluded, “Sam is still with the WRANGELL and has become as much a part of the ship as its rudder. It is impossible, of course, to know what he is thinking, but if we are permitted to hazard a guess, he very likely keeps saying to himself, ‘what a great bunch of guys I latched on to.'”

Sam did not just get a mention in the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s paper, but made several visits to the Yard himself. Capt. DeMetropolis was transferred to the Yard in July 1954, but Sam stayed aboard the Wrangell, in the care of at least one successive captain. Sam retired from sea service some time in 1955, and was “being kept by a former officer of the vessel,” the Shipworker noted. But he was in attendance at a ceremony held at the Yard in January 1956, when Capt. DeMetropolis presented his successor aboard the Wrangell, Capt. R.L. Fulton, with a Battle Efficiency Plaque for the ship. The paper noted that Sam also received a commendation at the ceremony that read, “To Sam … who had a great deal to do with the morale of the crew in helping win the Navy pennant.”

As an interesting side note, the Wrangell was involved in a rescue at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in March 1955. While the ship was in the Yard for repairs, a sailor fell into the East River while cleaning the side. As the sailor was unable to swim to shore or retrieve a life ring due to the shock of the icy water, Navy Yard rigger Joseph George dove into the river and supported the struggling sailor until the pair were fished out by a launch. For his courageous actions, George was awarded the Meritorious Civilian Service Award, the Navy’s second-highest civilian honor. It’s unknown if Sam played any role in the rescue.

Sam was not the last animal aboard the Wrangell, however. The former crew members I contacted also recalled the next skipper, Capt. Cooper Buck Bright, being a bit of an animal lover and a “character.” Jerry King remembered, “[Capt. Bright] let the men bring a donkey aboard in Greece, and then when time was up had the announce, ‘Get your asses off the gangplank and on this ship!’ so they could depart the Med.”

We don’t know Sam’s ultimate fate, but it sounds like he lived out the rest of his days with a sailor who loved and cared for him. Though we were really touched by the story of this loyal and beloved dog, “Sam” still didn’t seem to fit our new dog, but his nickname, “Salty,” certainly did. And then when we saw the picture of her in the Shipworker, unclear as it was, the resemblance was rather uncanny, and the name has stuck. She doesn’t take to the water like her namesake (and we have yet to take her out on a boat, let alone a Navy ship), but she’s every bit as loyal and loving. I’m sure she will have “a great deal to do with the morale” here at Turnstile Tours and help us to be happy and successful in the future.