Last week, Cindy and I spent our brief honeymoon in Newport, Rhode Island. Even though we were told to relax, how could we resist not doing a little bit of work while in the hometown of perhaps the most celebrated family in American naval history, the Perrys! We started our trip at the Naval War College Museum, which has many artifacts and exhibits about the famous Perry brothers, Oliver Hazard and Matthew Calbraith.

[Modula id=’1′]

This family not only is renowned for their naval exploits, but they have many connections to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Oliver lacks a Brooklyn connection (that I’m aware of, at least), but Matthew is closely associated with the Yard. From 1833 to 1837, we oversaw construction of the first steam-powered warship of the US Navy, the USS Fulton, at the Yard, during which time he also helped found the Navy’s first institution of higher learning, the Naval Lyceum, created the Navy’s first (short-lived) apprentice system, and served as the Yard’s second-in-command. By 1841, he himself had become the Brooklyn Navy Yard commandant. Of course, Matthew’s most well-known exploit was his journey to Japan in 1852-1854, which concluded with the Treaty of Kangawa, opening up Japan to foreign trade for the first time in over two centuries (with the exception of a few small concessions for Dutch and Chinese traders) and effectively ending the Sakoku period of isolation.

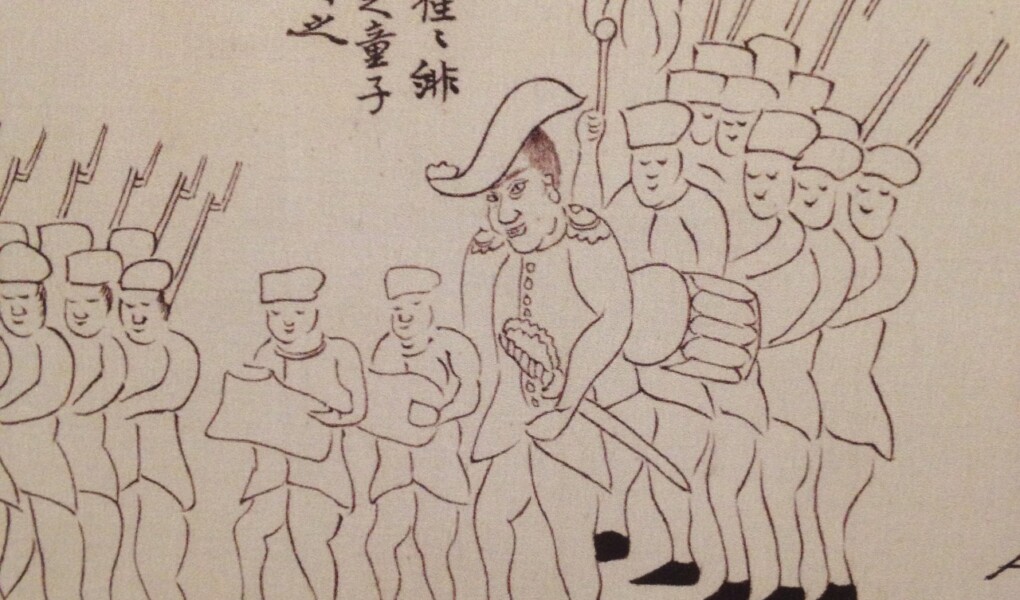

Above you can see artifacts from the expedition on display at the museum, including Perry’s sextant. Also on display are copies of the so-called “Black Ship Scrolls,” documents made by Japanese artists at the time of Perry’s visit to spread the news around the country. Many copies and versions of the scrolls were made, but only a handful have survived – the one belonging to the Preservation Society of Newport County and displayed in facsimile here is currently on loan to Brown University, which offers a complete, high-resolution digital version on their website, along with a full translation of the text.

Below these images are those of various Perry family graves. First, two images of Matthew’s sarcophagus in Newport’s Island Cemetery; next is an image of a fascinating little plot that can be found in Manhattan’s St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery. Matthew died suddenly in 1858 in New York City, and his body was placed temporarily in the vault of friend, John Slidell; in 1866, he was moved to his final resting place in Newport, though the New York grave marker remains. Below is the obelisk marking the grave of Oliver Hazard Perry, Matthew’s much older brother and the hero of the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. After several personal and professional dust-ups, he was dispatched to Venezuela to survey the Orinoco River, where he contracted yellow fever and died in 1819.

Of course, the whole Perry naval legacy really began with their father, Christopher Raymond Perry, who’s grave is next to Matthew’s. He served as a privateer in the American Revolution and became a decorated officer in the Navy of the early American republic. The elder Perry also has a Brooklyn connection – during the Revolution, he was captured and imprisoned about the HMS Jersey (from which he later escaped), the most notorious of the British prison ships moored in Wallabout Bay, the future site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.