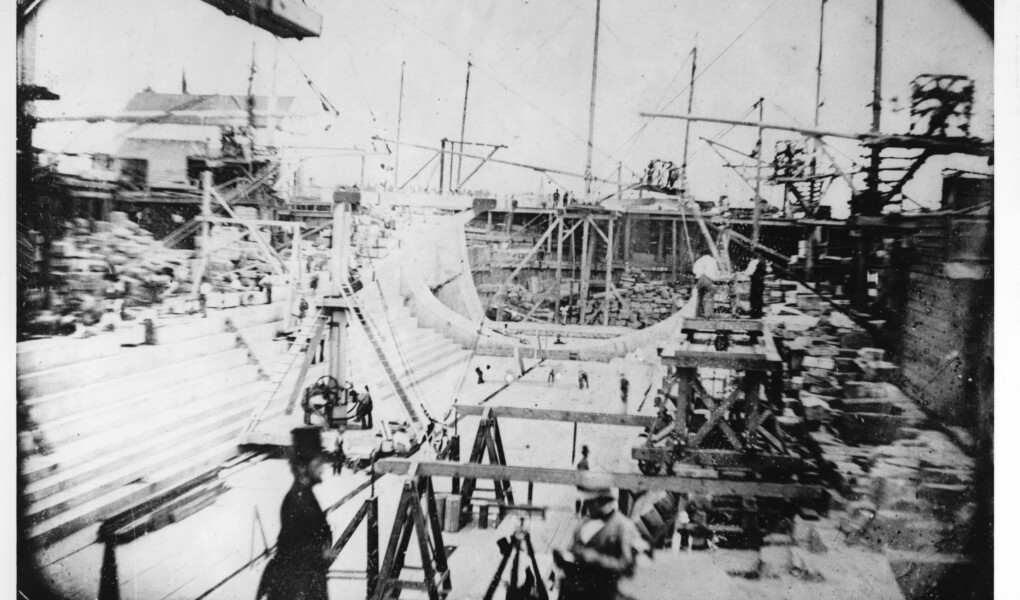

One of our favorite photographs of the Brooklyn Navy Yard is affectionately referred to as the “Lincoln photo.” We will be examining this photo more closely, and the scene depicted in it, on Saturday’s Seasonal Photography Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

As far as we know, the man pictured in the foreground with the giant stovepipe hat and chin beard is not Abraham Lincoln. Though it sure does look like him – at least, the construction-paper-hat-and-beard Lincoln of our elementary school book reports.When this picture was taken in 1846, Lincoln was just a candidate for the House of Representatives from Illinois. Who that man is, we don’t know [Ed. note: See update below], but what is going on in the background of this picture would play a large role in the coming Civil War and the presidency of Mr. Lincoln.

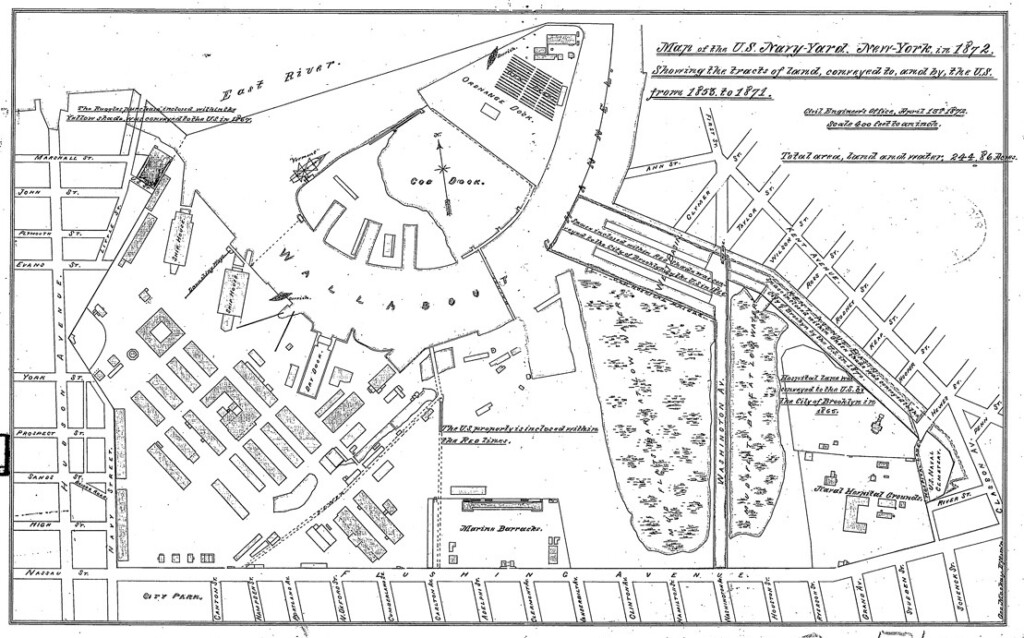

This scene is of the construction of the first dry dock at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Begun in 1841, this would be just the second third naval dry dock in the United States; it was a major technological innovation that would make the construction and servicing of ships much cheaper, faster, and safer, though building the dry dock itself was none of these things. It was a monumental project, taking more than 10 years to complete. Congress had originally apportioned $50,000 for its construction, but the final bill topped $2 million. When it was done, Charles B. Stuart wrote in his 1870 history of American dry docks, “It may truly be said, that no similar work of equal extent, and presenting so many difficulties, has been constructed in America, and but few, if any, in the world.” (For more on the history of the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s dry docks and how they function, read our earlier post.)

During the Civil War, the dry dock would be used to repair, outfit, and modify dozens of ships – more than 100 merchant ships were armed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and enlisted into the Navy during the war, though how many slipped into the dry dock is unknown. The most famous occupant of the dock was the USS Monitor, built up the East River at Greenpoint’s Continental Iron Works. The all-iron ship was then sailed to the Navy Yard to be outfitted with its revolutionary turret and armor plating [Ed. note: Though the Monitor was commissioned into the Navy at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and did have work done there, it never entered Dry Dock No.1, and was not fitted with its armor plate or turret there. The ship did suffer from a major steering malfunction, but designer John Ericsson refused to allow it to be dry docked, opting instead for a temporary fix.] Coincidentally, the Monitor‘s Confederate counterpart, the CSS Virginia-nee-USS Merrimack, was outfitted at America’s first naval dry dock, Dry Dock No. 1 at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia. Just days after the Monitor was completed, it would face off with the Virginia in the Battle of Hampton Roads on March 8-9, 1862. Though the battle was a draw, the Monitor neutralized the threat of the Confederates’ new super-weapon, maintaining the Union blockade of the South and keeping the Confederacy starved and isolated.

As for the picture itself, it is actually not a photo at all, but a daguerreotype. Invented in the 1820’s, daguerreotypes were an early form of photography that used a silvered copper plate to capture images. The original plate for the image is not at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but is property of the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, DC. The print that is in the Brooklyn Navy Yard archive is a photo taken of the original daguerreotype much later. In 1914, it was presented to the recently retired commandant of the Yard, Rear Admiral Eugene Henry Cozzens Leutze, who held command from March 1910 until June 1912. Interestingly, Admiral Leutze, who had previously been commandant of the Washington Navy Yard and commanded a ship in Admiral Dewey’s fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Spanish-American War, was born in Prussia. Despite his distinguished naval career, he probably got out of the Navy just at the right time, as the anti-German sentiment that would sweep the country during World War I would not have been a pleasant time for him. He would later return to Brooklyn, however, as he died in the Naval Hospital in 1931.

We like to pretend that Abraham Lincoln was captured here, surveying this monumental construction project. But even as president, Lincoln never visited the Brooklyn Navy Yard (though the first lady Mary Todd Lincoln did in May 1861 during a tour of New York). But the yard was on his mind – Lincoln complained to his Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, that workers and supervisors at the yard were less than committed to the Union cause, a common sentiment in deeply divided New York. Secretary Welles refused to make changes, noting in October 1862, “I was opposed to the policy of removals of competent officers unless for active, offensive partisanship; that any man was entitled to enjoy and exercise his opinion without molestation.” The Lincoln family would get over it, however, as his granddaughter Jessie Lincoln, daughter of Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, would sponsor the cruiser USS Atlanta, launched from the yard in 1884 (like the Monitor before it, this ship was also groundbreaking as one of the first steel ships of the US Navy).

If you want to get up close with these historical images and the sites in them, join us for our series of Seasonal Photography Tours of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. We will give you the opportunity to capture some of the iconic places of the yard, including Dry Dock 1, the Naval Hospital, and the yard’s piers. After the tour, National Geographic photographer and Navy Yard tenant Robert Clark will select his three favorite photos from the tour submitted to Instagram, and the selected photographers will win two free tickets on a future tour of the yard. As we will be offering this tour four times – once for each season – in 2013, a different professional photographer that works in the yard will make three selections after each tour, and the 12 finalists will be entered for the chance to win either the people’s choice award (picked by the public) or the photographer’s choice award (selected by our four professional photographers). The winner of each of those prizes will get a free private tour of the yard for themselves and their friends!

So, get your tickets and bring your camera, camera phone, or camera obscura out to the Brooklyn Navy Yard!

Turnstile Tours offers the Seasonal Photography Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard four times throughout the year – please check the tour page for exact dates. The tours will be offered Saturdays on January 26, April 20, July 20, and October 19, 2013, at 11am. Advance ticket purchases are recommended. We also offer our Overview Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard every Saturday and Sunday at 2pm during the winter months, and other special themed tours of the yard. All tours begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at Building 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the yard’s history, the Ted & Honey rooftop cafe, and a host of great special events and programs.

Special thanks to the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s archivist Meredith Wisner and Turnstile Tours guide Rich Garr.

Update: The person in this image could very well be William Jarvis McAlpine, who was chief engineer of the project from 1846 until 1849. He oversaw most of the major construction of the dry dock, including the pump house, main superstructure, and cofferdam, as well as the pile driving and much of the excavation. McAlpine would go on to become one of America’s leading civil engineers, building the water works for Albany and Chicago, and serving as Chief Engineer and Surveyor of New York state. In Brooklyn, he served on the Brooklyn Bridge Design Review Committee, and devised a (never implemented) plan for the city’s water supply. He also served as president of the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1868-69 – the image at left is taken from that organization’s history, written in 1897, though presumably the portrait was done during his term. The nose seems to fit, and the beard is plausible. But perhaps we’ll never know.