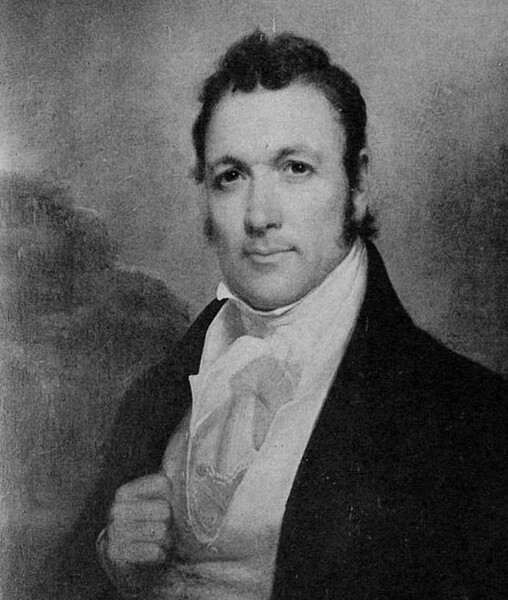

Henry Eckford (1775-1832)

The long, arduous, and risky journey to America has a way of bringing to our shores the most ambitious, talented, and daring people; Henry Eckford was certainly one of those. Born and raised in the Scottish town of Kilwinning, located not far from the famous shipbuilding center along the Firth of Clyde, Eckford set off from his homeland for Canada to learn the shipbuilding trade at just 16. Like John Barry, he apprenticed with his uncle, and became a skilled shipwright in the yards along the St. Lawrence River.

After completing his apprenticeship, and always with an eye out for his next opportunity, in 1796 he decided to test his luck in New York City. At just 21, he was hired by one of the East River’s most accomplished shipbuilders, Danish immigrant Christian Bergh, but he also designed and built ships in his own name. In 1803, he formed a partnership with Edward Beebe, and the two built ships for John Astor’s fur trading business and for the US Navy, until their partnership broke up in 1809. Eckford became renowned for his ability to design and build quality, fast, effective ships in a very short period of time. The US Navy recognized this talent, and when war broke out in 1812, Captain Isaac Chauncey – then commandant of the nascent Brooklyn Navy Yard – asked Eckford to establish a massive shipyard in Sackets Harbor, New York, on the shores of Lake Ontario, tasked with building an armada to counter the British. Eckford’s past experience working in the frontier conditions of Canada and nearby Oswego made him a perfect choice for the job, and he eventually had a workforce of more than 1,000 shipbuilders.

During the War of 1812, the Great Lakes became the center of a massive naval arms race; so much manpower and materiel was required that it sapped all the best talent from New York’s shipyards. Despite the austere conditions, Eckford delivered his first ship in just nine weeks, and he kept up his rapid pace throughout the war. He even began building what would have been the world’s largest ship, the 130-gun USS New Orleans, but the war ended before its completion. But the plan worked; though there were no decisive naval engagements on Lake Ontario (unlike on Lake Erie), Eckford’s flotilla had prevented the British from gaining control of the lake and mounting an invasion of New York. Eckford and Chauncey had won the “Battle of the Carpenters,” as it was known.

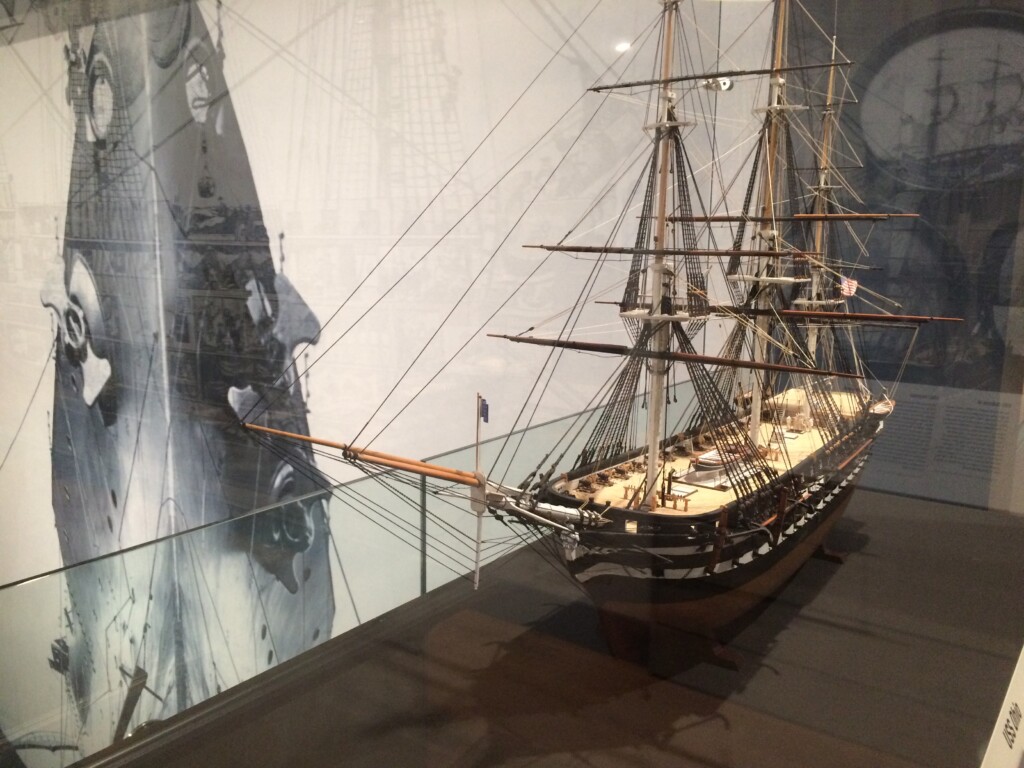

When the war ended in 1815, Eckford returned to New York, where he faced a post-war depression, and his business faltered. In 1817 he took the position of chief naval constructor at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where he designed the 74-gun USS Ohio. Launched in May 1820, the Ohio was meant to be one of the US Navy’s premiere ships-of-the-line, but budget cuts and political infighting led Eckford’s masterwork to sit, unused, for nearly two decades. Finally reconstructed in 1838, the ship went on to have a stellar career in the Mexican-American War, then spent most of the rest of her time afloat as a receiving ship – a floating barracks for enlisted seamen.

Eckford did not stick around to see his Ohio suffer these indignities; he tendered his resignation to the Navy just a week after the ship hit the water and returned to the private sector. He continued his business success, and even launched a political career in the infamous Tammany Hall organization, but public scandals and private tragedies, including the deaths of three adult children within a single year, took their toll on him. Looking for new opportunities, in 1831 he set off for the Ottoman Empire, hoping to sell his ships and services to their navy. He got the job, but barely a year after arriving in Constantinople, and already in the process of building two major ships for the Ottomans, Eckford died of an unknown illness.

Perhaps it was his attention to detail and his intolerance for waste that made him so successful. This account from his time at the Navy Yard appeared in an article about the history of New York shipbuilding from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in July 1882:

He seems to have had the instincts of a reformer, for one day, passing the blacksmiths’ shop, and seeing that the commodore’s horses were being shod there at the national expense, he ordered the grooms to remove the animals at once. “The business of this shop,” he said, “is to repair government vessels, not to shoe commodores’ horses.”

Though his time in the Brooklyn Navy Yard was short, Eckford left an indelible imprint on the US Navy and the entire American shipbuilding industry, and we have him to thank for the Yard’s very first ship. Revered by his fellow shipwrights, Eckford is commemorated in the name of one of the most successful baseball clubs of the 19th century, the Brooklyn Eckfords, which included many shipyard workers on its roster. You can also see some of Eckford’s handiwork in the lobby of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, where relics from the USS Ohio are on display, recovered from the ship’s wreck in Greenport, Long Island.