Three years ago, in celebration of Presidents Day, we wrote about the handful of times that sitting US presidents had paid visits to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. At that time, we only mentioned two such visits – by William Howard Taft, once as president-elect on November 13, 1908, and as soon-to-be-ousted-president on October 30, 1912, and by Woodrow Wilson, on May 11, 1914. But we have since done considerably more historical digging, and we would like to share a few more notable presidential visits.

Franklin Pierce

In July 1853, President Franklin Pierce embarked on a jaunt up the East Coast, stopping in Baltimore, Wilmington, Delaware, Philadelphia, and finally New York. On July 14, the president attended the grand opening of the Crystal Palace, the home of the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, located on the site of today’s Bryant Park (this remarkable structure burned down only five years later). The following day, the president was taken on a harbor cruise organized by the city’s Chamber of Commerce and attended by many leading businesspeople and dignitaries, including Brooklyn Mayor Edward Lambert. The trip was officially led by “The Committee on Encroachments on New York Harbor,” which was presumably created just for this trip, as we can find no other mention of it anywhere, nor do they specify what those “encroachments” are that they’re so worried about.

President Pierce did not technically set foot in the Navy Yard; rather, the steamer Josephine came through the Wallabout Bay and was greeted by “a national salute of 21 guns fired from the Receiving Ship North Carolina, at the termination of which the band on board the vessel struck up the inspiring strains of ‘Hail Columbia,'” as the New York Times reported. Though Pierce is not one of our most celebrated presidents, he did attempt to clean up corruption and graft – which was rampant at federal institutions like the Navy Yard – and the crowd that viewed his passing ship were, the Times noted, “cheering lustily.”

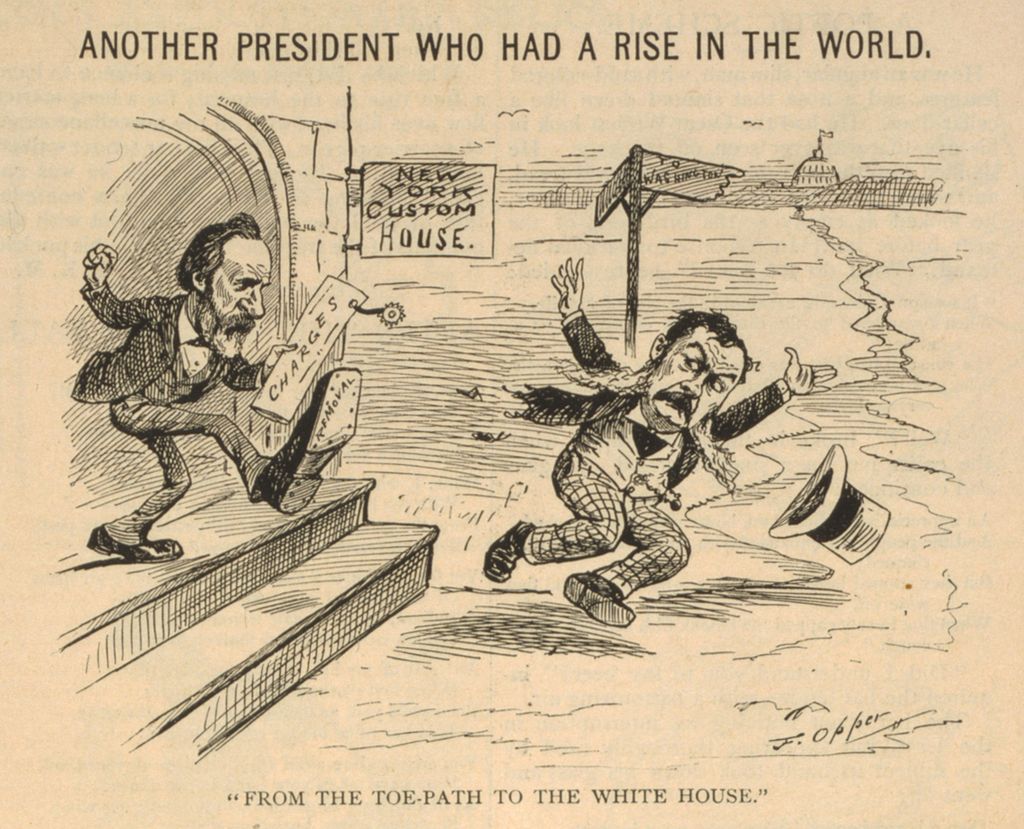

Chester A. Arthur

As far as we can reckon, nearly 30 years passed between presidential visits to the Yard (though First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln did visit in 1861 and 1862). That drought was ended by yet another unheralded chief executive, Chester A. Arthur, on August 11, 1882, though he too did not come ashore. Instead, his steamer Dispatch was greeted in the East River by the Yard’s training ship Minnesota, who fired the customary 21-gun salute. His party landed across the river at 23rd Street, where they were greeted by a Marine dispatched from the Navy Yard’s garrison.

Chester A. Arthur undoubtedly made many visits the Navy Yard before assuming the presidency. He was a big-wig in New York Republican politics, and he had spent seven years as the Collector of the Port of New York, responsible for the tariffs and customs imposed on goods passing through the country’s busiest port. The notoriously-corrupt Arthur enriched himself enormously at this post, until President Hayes had finally had enough of him, forcing him out in 1878. That did not end his political career, however, as he was tapped as the vice president to James A. Garfield, who was assassinated just six months into his term. Arthur did change his tune – or deftly sniffed the political winds – and supported the Pendleton civil service reform act, in large part because his popular predecessor had been killed by a disgruntled patronage-seeker. That did not, however, endear him to party bosses, who passed over him to nominate the even more corrupt James G. Blaine in the 1884 election.

Arthur also played a notable, if unimpressive, role in US naval history, authorizing the construction of the Navy’s first steel-hulled ships in 1883. Originally conceived by Garfield’s visionary Secretary of the Navy William H. Hunt as a fleet of 68 modern vessels, the compromise bill only authorized the four poorly-constructed, short-lived “ABCD” ships (Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin), and the reconstruction of some never-completed, obsolete Civil War-era monitors. Despite the disappointment of naval reformers, these projects did bring considerable work to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

William McKinley

While Arthur slowly began to modernize the US Navy, this process accelerated greatly under President McKinley and his successor-by-way-of-assassination, Theodore Roosevelt. A veteran of the Civil War, that experience had made McKinley acutely aware of the costs of war, and he was reluctant to lead America into another one. However, there was a growing imperialist constituency within his party, led by Roosevelt, who believed that America needed to play a larger role on the world stage, and the keys to achieving this were building a world-class navy and acquiring overseas colonies. The destruction of the Brooklyn-built USS Maine on February 15, 1898, in Cuba was the pretext they were looking for to go to war with Spain, and McKinley acceded to the wishes of the Roosevelt faction.

It was in this context, with America a newly-minted global power, that McKinley visited the Brooklyn Navy Yard on May 1, 1899. In fact, during the visit, he transmitted a telegram to Admiral of the Navy George Dewey to congratulate him on the one-year anniversary of his victory in the Battle of Manila Bay. Unlike previous visitors, McKinley did not just do a drive-by – his visit lasted more than an hour and included visits to the Naval Lyceum, the “Provisions and Clothing Storehouse,” and the Cob Dock, as well as tours of the ships Glacier, Yosemite, and New Orleans. While touring the storehouse, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “he sampled the coffee beans, examined the clothing and was interested in the machines which cut out a number sailor suits at once from a cloth.” (Incidentally, all of these things are done at the Navy Yard today – Brooklyn Roasting Company is moving its coffee roasting operations to the Yard, and Crye Precision is a manufacturer of military apparel and protective gear). The paper concluded, “No speeches were made and no undue ceremony was in evidence, but the visit was satisfactory and interesting to the President, who never failed to courteously acknowledge a salute from a man or a smile from a woman.”

Theodore Roosevelt

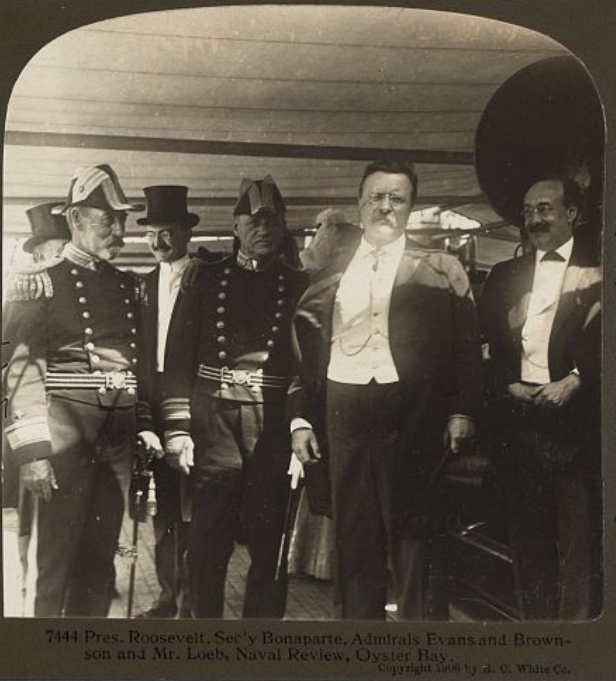

Few presidents have done more to shape the course of the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s history than Teddy Roosevelt (except that other Roosevelt, whom we will discuss later). There are also few politicians who have held more jobs in a shorter period of time. During his one year as Assistant Secretary of the Navy – after spending less than two years as New York City Police Superintendent and before spending one year as an officer in the Army – he conducted an investigation of corruption and unfair employment practices in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He declared the charges completely unfounded, a surprise to many who saw him as an anti-corruption reformer, but his tenure as president would bring sweeping changes to the Yard.

Following the Spanish-American War and the assassination of McKinley, Roosevelt made naval modernization a top priority. As part of his reforms, work was consolidated into the largest federal Navy Yards, rather than being doled out to smaller private firms. During his tenure, Brooklyn’s massive Dry Dock No. 4 was begun, as was the USS Connecticut, flagship of the Great White Fleet, which would circumnavigate the globe in a show of American power, and many other ships were planned and upgraded.

Despite his active role in naval affairs, it doesn’t appear as if Roosevelt made any high-profile visits to the Yard during his presidency. He preferred instead to have the Navy come to him at his summer home in Oyster Bay, as in 1903, when two ships collided close to his yacht, or in 1905, when he took a ride aboard the early submarine USS Plunger. Speaking of the president’s yacht, the records we do have of Roosevelt visiting the Yard were when the Mayflower dropped him off or picked him up en route to someplace else, as in this September 16, 1903 report from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Read our previous post for information about presidents Wilson and Taft.

Warren G. Harding

We found a passing mention to the Brooklyn Navy Yard during a visit to New York by President Harding on September 12, 1921. He also just stopped by the Yard to board the Mayflower, which served as the presidential yacht from 1905 until 1929. The privately-owned yacht was purchased by the Navy during the Spanish-American War, and refit and commissioned at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Like his distant relative before him, FDR was also a naval-minded president who had served as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. In this post, he had many occasions to visit the Brooklyn Navy Yard, including in 1915 for the launching of the ship that would play an outsized role in his presidency: the USS Arizona. Throughout his presidency, Roosevelt placed great importance on America’s naval strength, and as part of his pre-war expansion of the Navy, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was nearly doubled in size, adding many new facilities, including its two massive 1,092-foot dry docks.

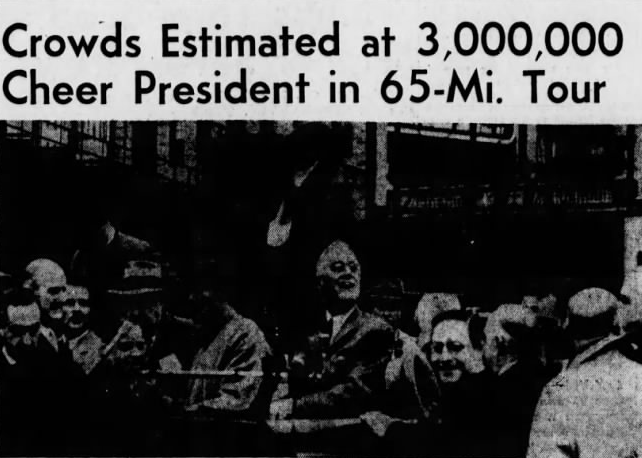

And like his predecessors, it’s likely that Roosevelt made many unheralded visits to the Yard, though aboard the presidential yacht Potomac. But in both 1940 and 1944, the capstone of his presidential campaigns were grand tours of Brooklyn, including visits to the Yard. On November 1, 1940, his motorcade passed by the Yard before he delivered a rousing speech at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. At the next campaign, on October 21, 1944, he made a 4-hour, 65-mile journey through the streets of four boroughs before an estimated crowd of 3 million onlookers, all in the pouring rain. This time, he did not just pass by the Yard, but spent roughly 20 minutes attending a brief ceremony behind BLDG 92. The Shipworker newspaper noted that he “made his tour of the Yard, by crowds of cheering workers, to the Hammerhead area, and back to Sixth Street, where parting honors were rendered.” The president then went on to a massive rally held at Ebbets Field.

Harry S. Truman

The last president to visit the Navy Yard, Truman’s ascent to the presidency likely changed the course of history for two of the Yard’s most famous ships. During World War II, the Yard had constructed two new battleships, Iowa and Missouri. When the war ended, and preparations were being made for a surrender ceremony by the Japanese, it was assumed that the Iowa, being the most decorated of the new class of battleships, and being the ship that had once hosted President Roosevelt, would host the ceremony. However, since the new president was a son of Missouri, the honor went to “Mighty Mo” instead. Truman had also attended the launch of Missouri on January 29, 1944, though at that time he was merely a US senator; his daughter Mary Margaret christened the ship.

Truman visited the Yard again on October 27, 1945, which was one of the largest naval reviews in American history. 48 ships crowded New York Harbor, among them the Missouri. The main event of the day was the commissioning of the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, attended by the president and the former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. So, that’s nine presidents who have visited the Brooklyn Navy Yard so far. As the Yard undergoes its greatest expansion since World War II, it’s conceivable that a current or future president could stop by as well.