At 3:57 p.m. on May 2, 1982, the British submarine HMS Conqueror fired a spread of three torpedoes at the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano, located approximately 230 nautical miles southwest of the Falkland Islands. Two of the weapons found their marks, fore and aft of the ship’s protective belt armor on the port side. In less than 30 minutes, the order was given to abandon ship, and Belgrano sank, taking 323 souls with her.

In those frantic minutes, as sailors tried desperately to navigate the smoke and fires, 30-year-old Lieutenant Martín Sgut took command of a lifeboat and lowered it into the water. As he and 11 shipmates, one of them dying in his arms, drifted away from the sinking hulk, Lt. Sgut snapped a series of pictures that would become the center of a legal and political maelstrom, and the iconic images of the Falklands War.

South America’s Battleship Race

The ship in that photo did not begin its life in Argentina, but Philadelphia. Built in 1938 as the Brooklyn-class light cruiser USS Phoenix (CL-46), it saw extensive service in the Pacific in World War II. After the war, the United States possessed a gargantuan military arsenal, and the 1949 Mutual Defense Assistance Act was passed to transfer these arms to friendly countries around the world. The bulk of this equipment went to members of the newly-created NATO alliance, but also to nations that were key to the American containment strategy, especially in Asia and Latin America.

Six World War II-era light cruisers were selected for transfer to Brazil, Chile, and Argentina in 1951. Brazil received Philadelphia and St. Louis, Chile Boise and the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built Brooklyn, while Argentina got Nashville and Phoenix. Over the next 25 years, the US would transfer 10 destroyers, 11 Tank Landing Ships, four submarines, and many other smaller support ships to the Argentine Navy, with similar numbers distributed to Chile and Brazil.

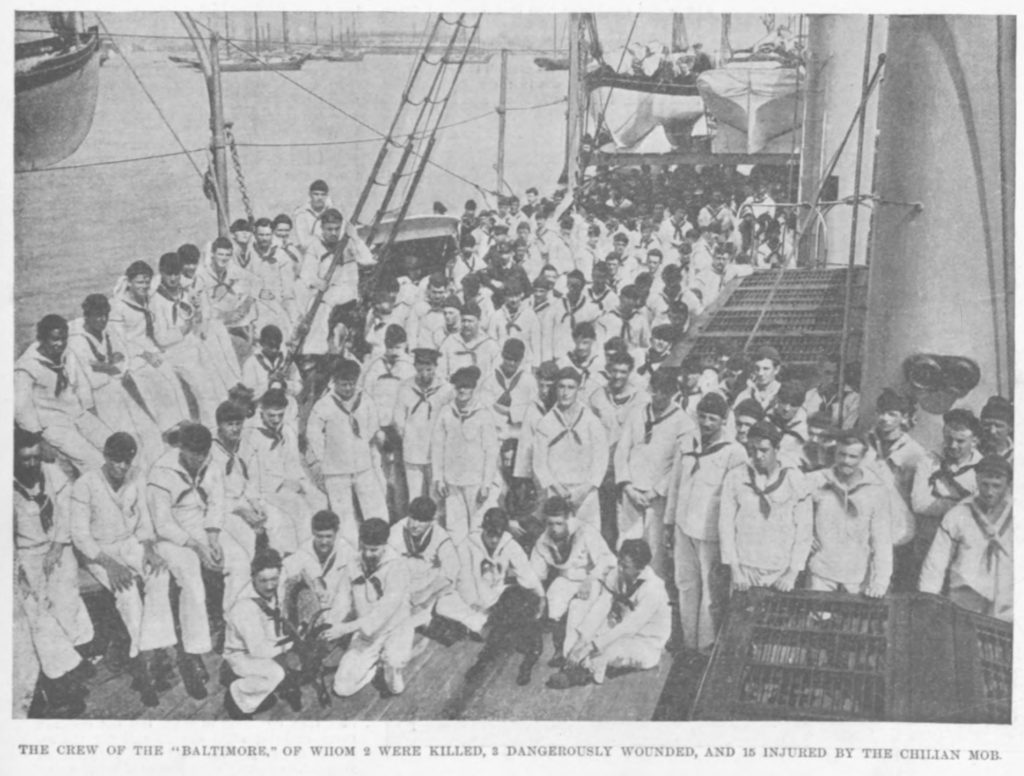

This was not the first time that the US had become involved in the naval affairs of these three countries, all of which had a long maritime rivalry dating back to their founding as independent states. In the 1870’s, they began purchasing ironclad warships from European builders and expanding their fleets greatly, as the region was embroiled in a series of wars between various combinations of the three big powers and their smaller neighbors, and these purchases accelerated in the following decades. By comparison, America’s Navy was relatively weak; in 1891, an incident in which two American sailors were killed in a Valparaiso bar nearly escalated into a war with Chile. The conflict was settled diplomatically in part because the US Navy feared they would lose.

In 1905, Brazil authorized funding for a trio of the newest British-built, dreadnought-style battleships, bringing the arms race to a new level. Chile and Argentina responded by each ordering a pair of their own, with the Argentine ships coming from the United States. Built at Massachusetts’ Fore River Shipyard, Moreno and Rivadavia would both visit the Brooklyn Navy Yard for dry docking and painting before embarking on their sea trials; they entered Argentine Navy service in the winter of 1914-1915. Unfortunately for the two Chilean ships, because they were built in Great Britain, the British government seized them for the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the First World War I – one wasn’t delivered until 1920, while the other wasn’t delivered at all, instead becoming HMS Eagle.

These ships all turned out to be white elephants – by some estimates, these battleship purchases consumed one-quarter of the each government’s entire annual budget. Combined with their astronomical costs, a series of economic calamities, political crises, and mutinies rendered the ships essentially inoperable and useless. Brazil tried to keep their ships up to date, modernizing Minas Geraes and São Paulo at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1920-21, but by the outbreak of the Second World War, none of these ships were fully operational.

From the South Pacific to the South Atlantic

USS Phoenix was present the attack on Pearl Harbor, surviving unscathed, and spent most of the war operating in the Southwest Pacific, around New Guinea and the Philippines. After a stint in mothballs at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the ship was converted for foreign sale — Argentina paid an estimated $2 million, or 10% of the original construction cost, as stipulated in the MDAA. The transfer was completed on October 17, 1951, a date that was not coincidental, as it was also the new name of the ship, ARA 17 de Octobre, commemorating the beginning of the country’s Peronist movement in 1945. That name would be short lived, as after Juan Perón’s ouster by a military coup in 1955, it would be renamed for Argentine sailor and independence leader Manuel Belgrano.

ARA General Belgrano’s service career would be rather uneventful for the next 27 years, until the outbreak of the Falklands War on April 2, 1982. Claiming the British territory for itself, Argentina launched an invasion of the Falklands, as well as uninhabited South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Argentina’s military junta assumed, incorrectly, that Britain would not attempt a military solution to the conflict, yet the British armed forces hastily assembled a naval task force to deliver ships, aircraft, and ground troops 8,000 miles to the South Atlantic to retake the islands.

With the massive convoy steaming south, on April 23 Britain imposed a 200-mile maritime exclusion zone around the Falklands, declaring that any ships within that zone could be attacked. By the end of the month, the main body of the convoy had arrived off the islands, and the conflict began to heat up considerably. Argentina could threaten the British fleet with both its naval forces, which included the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo, as well as jet fighter-bombers, including Super Étendards armed with deadly Exocet anti-ship missiles.

The Argentine fleet was broken into three task forces to surround the islands, two covering the approach from the north, and one, led by Belgrano, positioned to the south, with the intention of encircling the British as they arrived. When British intelligence received word of the southern task force’s movements, it was decided to attack it to prevent this pincer maneuver. On May 2, Conqueror launched its attack.

A Sailor and His Camera

As Lieutenant Sgut made his way to the ship’s main deck, he saw a sailor laying motionless with severe burns, Corporal Orlando Escobar, so he picked him up and carried him to the lifeboat. Sgut remembered he had managed to rescue his camera, which still worked despite a good drenching, so he took a few pictures over the next half hour as the ship slowly disappeared into the ocean. Now he and roughly 700 other survivors were adrift in the icy South Atlantic, the other ships in their task force fleeing the scene under threat of another submarine attack. It would be another 24 hours of waiting in subzero temperatures and 18-foot seas before rescue would arrive. By then, Corporal Escobar was dead.

Upon arriving back at the naval base in Ushaia, Tierra del Fuego, Sgut turned his film over to Argentina’s Naval Intelligence Service, believing it was highly sensitive material. To his – and the world’s – shock, his pictures would appear on the front page of the Sunday New York Times on May 9, and from there they were transmitted around the world, arriving back in Argentinian papers by May 13.

The sinking of Belgrano had already been a shattering blow. Argentina withdrew its navy to their homeports, including the powerful northern task forces, and would instead rely on air attacks from bases on the mainland – all at least 400 nautical miles from the battle zone – to repel the British landings. Britain would suffer its own losses, including two destroyers and two frigates, though none incurred the same loss of life as Belgrano. But the appearance of those images in public would deliver another blow to Argentina’s public confidence in the war, and in the regime that was prosecuting it.

Like all wars, this was a war of propaganda. Argentina was ruled by an oppressive and murderous military junta, and press censorship was widespread. The regime was torn between the desire to suppress news that the war was going badly, and the desire to position themselves as the victims of a heinous war crime. When asked by the Times to corroborate the photos’ authenticity, the Argentine government tried to stop or delay their publication, and local press was touting the impending victory. When censorship was no longer possible, the regime pivoted to victimhoom, calling for international condemnation of the sinking. Meanwhile, Britain claimed its right to intercept threats outside the exclusion zone, and evidence, including intercepted communications and later admissions by the ship’s Captain Héctor Bonzo, would prove that the homeward course was a feint, and Belgrano had every intention to take aggressive action.

[Note: The sinking of Belgrano remains controversial in both Argentina and the UK, in part due to the questionable justification and the enormous loss of life, but Argentina’s own navy accepts the determination of international tribunals that the sinking was a permissible act of war.]

So how did the photos wind up in the foreign press? Silvio Zuccheri, a photographer with ILA, an affiliate of French news agency Gamma, was sent to the coastal city of Bahìa Blanco to photograph survivors of the sinking. There he met intelligence officer Lieutenant Commander José Garimaldi, who claimed to have a “bomb” for him: four photos of the actual sinking, available for the price of $1,000 per photo. Unable to afford it himself, Zuccheri pooled funds from other publications and got the photos – but just for one hour. Garimaldi let him take the prints, but no negatives, to duplicate, which he did by photographing them in his hotel room. From there the photos went to New York via Gamma, and Sgut’s name was never mentioned.

Fast forward two years: the war is long over, Britain has retaken the Falklands, the military junta has been toppled, and Martín Sgut has filed a lawsuit in New York. The suit claims that news outlets, including the Times, Newsweek, the Associated Press, and Gamma, published stolen works without attribution and profited from them, and Sgut is asking for $2.75 million in damages. Ultimately, he prevails, but for a much smaller sum of $20,000, which he donates to a fund for the families of his lost shipmates, and he is acknowledged as the rightful creator of the photos.

After leaving the Navy, Sgut went on to have a successful career as a maritime engineer, working on port projects in 34 different countries. He died of cancer in 2010 at age 58. José Garimaldi was prosecuted for illegally selling the photos. He died in 1994. Silvio Zuccheri is still working as a photographer, and you can follow him on Instagram.