In a strange coincidence, New York City’s two tabloids, the Post and the Daily News, have unleashed a one–two punch against street vendors this week. In depicting vendors as unsanitary scofflaws and freeloaders, these articles use a few atypical examples to mislead the public and turn opinion against vendors.

The Post got things started on Monday with an item about vendors who “rake in the bucks” but “don’t pay a cent for rent.” The article highlights several long-standing vendors who have lucrative, high-traffic locations in Manhattan, but supposedly pay only $200 for their right to vend wherever they please.

The Daily News takes another tack, pointing out the millions of dollars in unpaid fines that vendors have accumulated over the past few years. Based on thousands of reports from the Department of Health, the article implies that all street vendors “run the gamut of gross — bugs in the grub, working with grimy hands or storing food at improper temperatures.” They use as their poster child an Egyptian-born vendor in Brooklyn who recently moved locations to “escape city inspectors” after receiving a violation.

These articles are, unfortunately, pretty par for the course from these dailies. The hard work and quality food of vendors, or the broken and unfair system that targets the most vulnerable businesspeople in the city, is rarely part of the story. All we hear about is how vendors are pulling a fast one on ordinary New Yorkers, working rent-free and ignoring their tickets while they endanger our lives.

So let’s set the record straight.

Let’s turn to the Post story first. Street vendors may not pay traditional rent for their sidewalk locations, but the costs of running a cart are significant. All vendors must rent space in a city-licensed commissary garage, where carts and trucks must be stored and cleaned every day. Rent can range from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, depending on the size of the cart or truck and the location of the garage. On top of that, most vendors need to do prep work for the food they serve, which can only be done in a licensed commercial kitchen, so add several hundred more bucks to the monthly tally. Not only that, but the amount of available sidewalk space is shrinking, as more streets become off-limits, or space is gobbled up by CitiBike stations.

The $200 permit figure is also very misleading. Because there is a cap on the number of mobile food vending permits, and they can be renewed in perpetuity, and holders can pass them down to their children, very few permits become available for the $200 price tag. The waiting list from the Department of Health is estimated to be anywhere from 10 to 20 years long, and getting longer. So, how do new food vendors set up shop? They rent permits from existing holders – the going rate today can range from $10,000 to $20,000 for that two-year stretch, and as more and more well-capitalized food truck businesses enter the market, prices are getting pushed up.

Let’s not forget that most of the vendors profiled by the Post have been working their corners for years, so let’s not begrudge them their success in their line of work. If you want to get up every morning at 4am, prep and cook food in a commercial kitchen, push a 500-pound cart halfway across Manhattan, work outside in the heat, and cold, and rain, and snow, selling food for decades, be my guest. I’m sure you’ll be a millionaire in no time.

Tickets are another significant cost that vendors bear, but they don’t receive them because they all play fast and loose with the law. Let’s break down the numbers that the Daily News gives us: 7,124 tickets issued by the Department of Health in the past year to mobile food vendors. There are 5,100 licensed street food vendors in New York City, and probably a similar number of unlicensed ones. Taking the range of these numbers, that means the average street vendor receives somewhere between 0.7 and 1.4 tickets per year – hardly a huge number of violations for an industry where people work every day on the streets under the scrutiny of nearly a dozen city regulatory agencies.

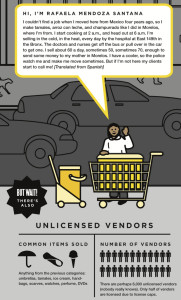

But let’s look at the top three violations that the Daily News cites. 1,092 tickets were issued for storing food in a cooler not attached to a cart, something that hardly sets off alarm bells for public health advocates. The second-ranked violation – operating without a permit – is a more serious violation, but the article fails to examine the larger forces at work here. The cap on the number of permits is largely unchanged for 30 years, despite increases in population and demand (not to mention declining employment opportunities elsewhere). Most of the permitless vendors are immigrants trying to navigate the complex and confusing city bureaucracy and engage in a business many of them brought from their country of origin. Rather than saddle them with millions in fines, the city should expand the number of permits and look for ways to offer more opportunities for these small businesspeople.

And coming in third, 557 tickets were issued for operating without the city-mandated mobile food vending license. While permits attach to each cart or truck, the license must be held by every person working on the cart – to get one, you must take a two-day course in food handling and safety. Judging from years of experience working with vendors, it’s likely that many (if not most) of those tickets were issued not for being without the license, but for not properly displaying it – that is, having it in your pocket instead of around your neck when serving food. Interestingly, there were fewer of these tickets issued than for vending without a permit, meaning many of the vendors who could not secure a permit for their mobile food business still took the care to receive proper certification in food handling.

Finally, let’s address the issue of unpaid fines. If upwards of 65% of fines go unpaid (and in previous periods, that figure approached 95%, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office), perhaps the problem goes beyond vendors’ unwillingness to pay. Tickets usually come in bunches (as tickets tend to in our “performance metrics”-based city bureaucracies), saddling vendors with thousands of dollars in fines that they cannot ever hope to pay off. So rather than pay them, most make the rational decision to keep working until someone takes their business away. This is no way to run an effective, equitable regulatory regime. And rather than fix this, the mayor has decided to double-down by creating a shakedown crew of lawyers to pursue these vendors to the ends of the earth. The City Council recently addressed this issue in their overhaul of the fine structure of street vendors by mandating that any agency issuing a ticket to a vendor record the number of the permit on the cart as well as the person’s name, making it easier to track repeat offenders and hold them responsible. But this is just a first step.

Unfortunately, there are some street vendors who run unsanitary businesses. But these articles take advantage of the public’s unfamiliarity with street vending and rely on nativist sentiments in order to single out an entire industry as scofflaws and threats to public health. Most vendors are trying their best to build their businesses, support their families, and navigate a system that is stacked against them, and in doing so, they deliver to the public delicious, affordable food.

Want to learn more about street vending in New York City, taste the food of some of the best vendors, and support advocacy efforts and legal aid services for vendors? Join us at the 2013 New York City Vendy Awards, held Saturday, September 7, in Brooklyn’s Industry City. See this year’s nominees and get tickets here.

Turnstile Tours offers weekly tours of food carts and trucks year-round, every Wednesday at 12pm in Manhattan’s Financial District, and every Friday at 2pm in Midtown. These tours include tastings from six different vendors, and visitors learn about the history of vending in New York City, the rules and regulations affecting vendors, and they even have the opportunity to meet the vendors themselves and ask about what it takes to run one of these small businesses. At least 5% of all of our ticket sales goes to support the Street Vendor Project. To join us, visit our tickets and information page.

This post was authored by Andrew Gustafson.