On the evening of Friday, November 7, the tanker ship Rainbow Quest collided with the Brooklyn Bridge. The collision was minor, as the ship’s light tower just scraped the underside of the roadway. While the accident caused a minor sensation – and quite a few traffic delays, though no discernible damage – close encounters between ships and the Brooklyn Bridge are nothing new, and its relatively low clearance has been the subject of vicious political battles for nearly 150 years.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration considers the center of the Brooklyn Bridge’s span to be 127 feet above the East River’s mean high tide. According to the ship’s statistics filed on eFleetWatch, Rainbow Quest ranges from 112 feet to 144 feet above the water, depending on her load – well within the range to strike the bridge. We still don’t know what exactly caused the miscalculation, but they weren’t the first, and they won’t be the last to make that mistake. According to the Coast Guard Maritime Information Exchange, this was the third “allision” (a fancy maritime word for when a vessel hits a stationary object) with the Brooklyn Bridge since 2002.

Almost from the moment a bridge connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn was proposed, people feared that any such project would be an impediment to navigation, stifling commerce in the nation’s busiest port, and threatening national security by limiting access to one of our most prized military and industrial assets, the Brooklyn Navy Yard. After the design was completed and construction began in 1869, for a bridge with a center span height of 135 feet (NOAA uses a more conservative estimate of the bridge height, or “air draft,” than is commonly cited for the bridge), many lawsuits were filed against the bridge’s designers, builders, and financiers.

Many ships of the day had masts well over 135 feet, but the bridge’s builders felt that, given the already enormous engineering challenges of building the world’s longest suspension bridge, this height would offer safe passage to most vessels, while ship’s that were too tall could remove their topmasts, or find berths elsewhere in the harbor. Yet a lawsuit filed in 1876, led by warehouse magnate Abraham Miller and co-signed by no less than 32 other shipping, trading, and dock companies, claimed that the bridge violated the wishes of Congress that the “bridge shall be so constructed and built as not to obstruct, impair, or injuriously modify the navigation of the river,” and they demanded its immediate removal. The City of New York also tried to withhold money from the bridge project, leaving the then-independent City of Brooklyn holding the bag, claiming that the bridge was too expensive and was too large an impediment to commerce. But the bridge eventually prevailed; by 1879, these suits were thrown out, and New York City had to pony up the cash to finish the bridge.

But the bridge’s critics weren’t entirely wrong. The first recorded collision of a ship with the Brooklyn Bridge was actually long before the bridge was even completed. On May 11, 1878, the US Navy training ship USS Minnesota struck one of the suspension cables strung between the bridge towers. Apparently the sailors knew that the ship would not clear the wires, so they had already lowered their topmast in preparation for their scheduled passage from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the west side of Manhattan. Unfortunately, according to a report in the New York Daily Tribune, “but having to change her course to pass another vessel under the bridge, the tip of her main top-gallant mast caught in one of the storm wires and broke off.” No injuries were reported, and Minnesota required only minor repairs.

On September 29, 1882, by which point the bridge was nearing completion, the merchant ship Undaunted struck the center of the roadway, knocking out her topmast and a small section of the bridge. Luckily no one was hurt, and the New York Times described the damage to the bridge as “trivial,” adding, “One of the officers who was upon the structure at the time of the collision says that the shock was no greater than that which occurs when a plank is thrown down.”

From the perspective of the Navy Yard, the Brooklyn Bridge was designed in the era of steam-powered sailing frigates, but by the time it was completed, steel-hulled cruisers and battleships were entering the navy, and the exponential rise in the size and firepower of ships in the following decades would make the bridge’s once-adequate headroom a tight fit. In 1915, the former Secretary of the Navy George Meyer complained that “the Brooklyn Navy Yard … is located where a modern navy should not under any circumstances be located,” in large measure, he argued, because “the height of fire controls in our navy is governed by the height of the Brooklyn Bridge.” (He was referring to the then-new fire control masts, also called lattice or cage masts, which allowed spotters to direct the ship’s guns by sight, before the era of radar and naval aviation).

New York City’s bridges would play a central role in the country’s preparations for World War II. In 1939, the War Department quashed Robert Moses’ grand plan to build a suspension bridge from Lower Manhattan to Brooklyn. They claimed that two bridges (Brooklyn and Manhattan) blocking access from the Navy Yard to the sea were bad enough; adding a third, much larger bridge would only increase the danger of the Yard being cut off in wartime if one were to be destroyed (and if you thought ships could then just come from the north via Long Island Sound, in that direction there are six bridges with comparable clearance as the Brooklyn Bridge). Eventually the bridge project was replaced with the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel.

By the outbreak of World War II, the Brooklyn Bridge had become a major impediment, and many of the Navy’s largest ships – especially aircraft carriers – could not squeeze into the East River. In 1941, the Navy began constructing the Brooklyn Navy Yard Annex in Bayonne, NJ, which would include an enormous 1,092-foot dry dock, the same size as the two other new dry docks being constructed at the main shipyard. This would give the Navy a facility to repair ships without having to worry about the low bridges, but the annex could also be used to remove radio masts and stacks from ships, allowing them to fit under the bridge and have their primary work done at the much larger and better equipped yard; when the work was completed, the process would be reversed, as ships would return to Bayonne to have their masts replaced.

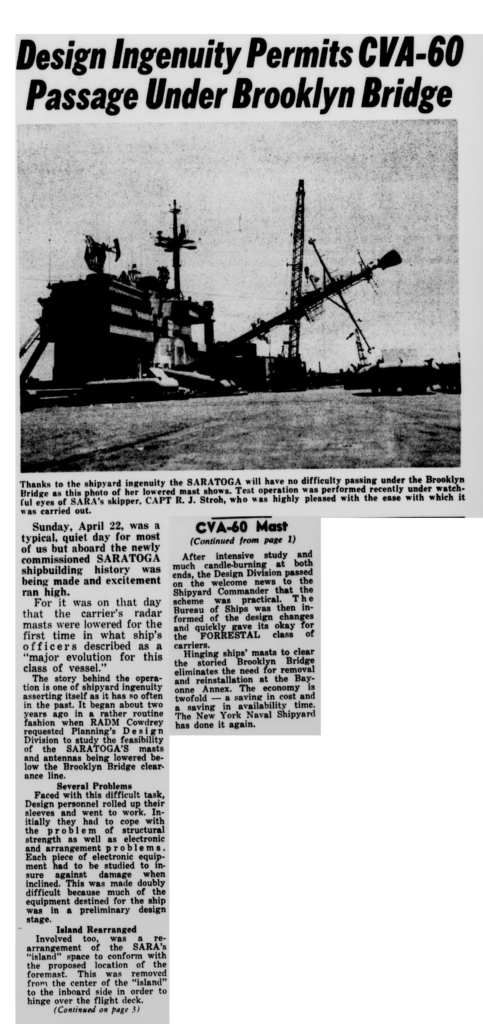

In the post-war period, with the development of the new class of “supercarriers,” the Navy would have to find a way to fit these enormous vessels under the bridge. The solution to this problem was found by engineers at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, who were working on designs for the Forrestal-class ships. While the Navy had considered making the carrier’s “island” (the structure that juts up from the flight deck and contains the ship’s bridge and control tower) fully retractable to make it flush with the flight deck, this proved far too complicated. Instead, the Yard’s engineers decided to design hinges for the radar masts and communications antennae so that they could be folded down, thus lowering the ship’s overall height by more than 60 feet. This ingenious design was then passed along to Newport News Shipbuilding, which was constructing the lead ship of the Forrestal class, and was then employed on the Brooklyn-built carriers Saratoga, Independence, and Constellation. When the Independence sailed under the Brooklyn Bridge for the first time, Life magazine reported that there was only seven feet of clearance above the ship, and only five feet between the ship’s keel and the riverbed.

While the reasons for the closure of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1966 are varied and complex, there’s little doubt that the obstacle posed by the East River bridges at least entered into the Pentagon’s thinking. Vessels still visit the Brooklyn Navy Yard today for repair work at the GMD shipyard (presumably what the Rainbow Quest was doing there, though we haven’t be able to confirm this), but GMD also operates the former Bayonne Annex, allowing them to work on ships that cannot fit under the bridge, just as the Navy intended. Today the bridge is much less of an impediment to the Navy or to maritime commerce, as the former has left the harbor entirely, and the latter has largely relocated to facilities on the New Jersey side.

And on the west side of the harbor, there is a far more important obstacle to consider: the Bayonne Bridge. Standing just 151 feet above the water, this steel arch bridge hinders access to the container ports in Newark Bay. Because it spans one of the busiest shipping lanes in the country, plied by enormous container ships, allisions are far more common (at least 10 since 2002). This is why the Port Authority is spending $1.3 billion dollars to raise the roadway of the bridge 64 feet, bringing it more in line with the dimensions of the expanded Panama Canal (called New Panamax standards), allowing the port to remain globally competitive.

Turnstile Tours offers several tours that highlight New York’s waterfront, past and present. We offer our Past, Present & Future Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard every Saturday and Sunday afternoon, and other special themed tours of the Yard on select weekends. All tours are offered in partnership with and begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the Yard’s history, and a host of great special events and programs.