As we reflect on the deeper meaning and troubling implication of the US president describing certain foreign countries as “shitholes,” it has also opened an opportunity to think critically about how and why these places became impoverished. Often, European and American imperial intervention – or outright exploitation – played a significant role. While we celebrate the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a center of innovation, labor, and service, we must also recognize its role in projecting American power across the globe, sometimes for less-than-noble ends.

Take Haiti, the world’s first free black republic, founded as the result of a slave rebellion against French colonial rule. Following the revolution, France and the Great Powers attempted to strangle this young nation in the crib, placing trade embargoes and saddling it with astronomical debt. The United State has a long and complicated history with the second-oldest republic in the Western Hemisphere, but the height of US involvement was when the American military occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934. Many of the actions of this military operation originated 1,300 miles away in Brooklyn.

After struggling for a nearly a century to pay an astronomical debt of 90 million gold francs to France – a condition imposed for recognition of the free nation in 1825, and not paid off until 1947 – Haiti was firmly within the economic orbit of the US, which controlled its banks and sugar trade. Haiti’s politics had become increasingly unstable in 1915; a series of coups and assassinations had produced seven presidents in just three years, making American business interests nervous.

These interests, as well as fear of growing German influence on the island in the midst of World War I, compelled President Wilson to dispatch sailors and marines to the island. The battleship USS Washington landed the initial invasion force of 340 sailors and marines in the capital Port-au-Prince on July 28, 1915, just hours after the assassination of Pres. Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam.

Seven months prior to this, marines from the gunboat USS Machias came ashore and seized $500,000 in gold from Haiti’s National Bank, which had recently come under the control of the National City Bank of New York (now known as Citibank). The ship returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and the gold was placed in National City’s vaults “for safe keeping.”

There was little resistance to the American invasion, though one Haitian soldier stood his ground at Port-au-Prince – and Pierre Sully was killed by American troops. Within 48 hours, the first Americans were killed – though not by Haitians.

During the second night, as US forces secured the capital, there was anticipation that forces loyal to would-be president Rosalvo Bobo would attack, though it never came. Nevertheless, American forces were on high alert. A detachment of sailors were patrolling the city, and two of them, Cason S. Whitehurst and William C. Gompers, were sent ahead to investigate a noise. When they returned to their unit, who had barricaded themselves inside a building, they knocked to be let in. The sailors inside, fearing it was the enemy, fired through the door, killing both.

Official reports claimed that the sailors were killed by Haitian snipers, which only heightened tensions in what had become a relatively calm situation with little actual fighting. Major Smedley Butler of the US Marines would later write of this incident:

“… those two bluejackets were shot and killed by their own men, poor devils. These d–d jackets have been shooting at everything that walks aside from which racket everything is as quiet as a grave ashore here. The Marines, so far, have not heard of any hostile forces and really these natives are apparently overjoyed to have peace.”

Gompers was from Brooklyn; he lived at 107 Stockton Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant, just 15 blocks from the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Born on October 21, his middle name was Columbus, in honor of the date the explorer first sighted land in the Bahamas; ironically, Gompers would also spend much of his career in the Caribbean. He enlisted at 17 and spent three years aboard the battleship USS Idaho.

After being transferred to the Washington in 1914, it was dispatched to the Dominican Republic to quell political unrest, and then to Mexico, where the US had become embroiled in the civil war. A few weeks before Washington’s arrival, in April 1914, 17 American sailors and marines had been killed in the invasion and occupation of Veracruz. Their remains were returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where President Wilson eulogized them.

Gompers’ body also returned to the Navy Yard, but with far less fanfare than the 10,000 mourners who had come one year earlier. On August 15, a small ceremony was held at the Brooklyn Naval Hospital, and the coffin processed to Cypress Hills National Cemetery, past his mother’s house on Stockton Street, where more than 100 friends and family had gathered. At the gravesite, a eulogy was given by his uncle, American Federation of Labor president Samuel Gompers. His nephew was just 22.

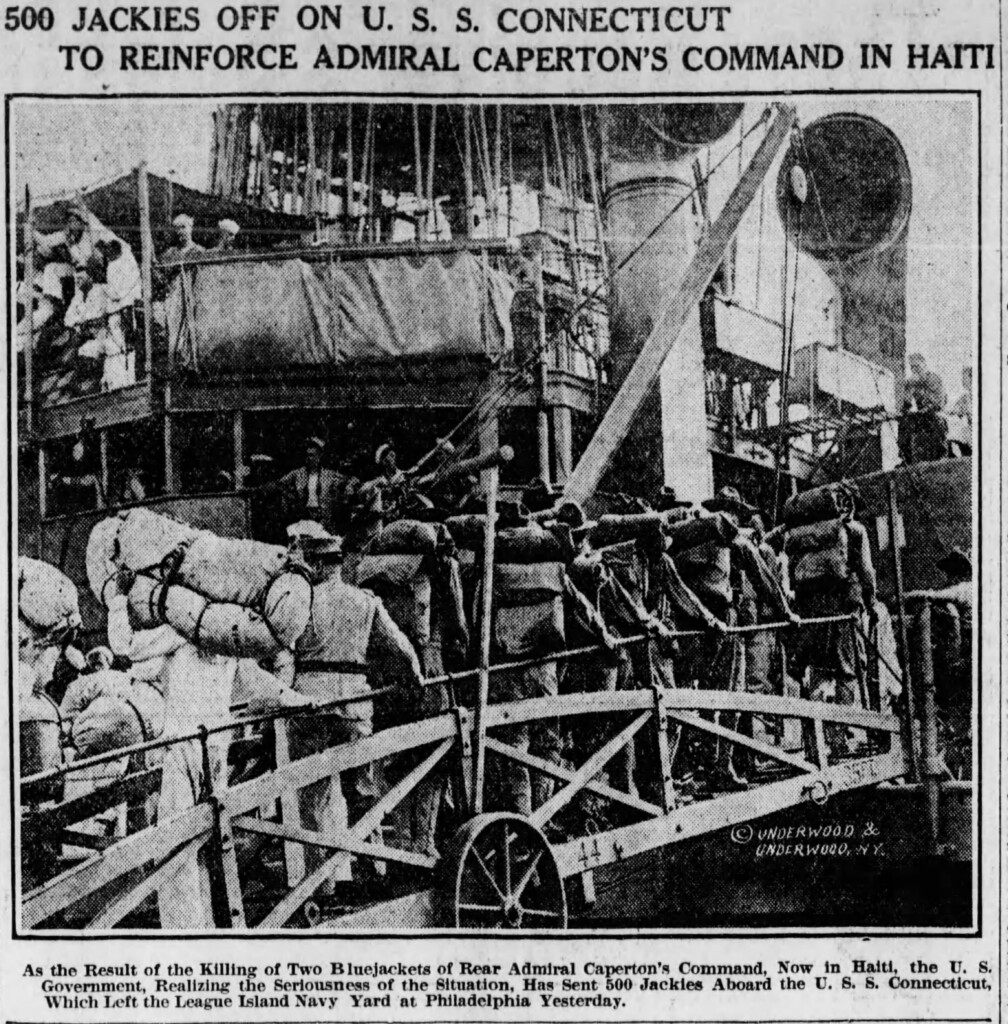

Meanwhile, the killing of Gompers and Whitehurst was used as a pretext to ramp up involvement in Haiti. On July 31, 500 marines were embarked at Philadelphia aboard the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built USS Connecticut. It was rumored that these troops had come entirely from Brooklyn’s marine detachment, when in fact only about 25 had been dispatched to Philadelphia.

The sailing of the Connecticut is when “Old Gimlet Eye” Smedley Butler arrived in Haiti. Butler was also an old hand in the Caribbean; he had served in Puerto Rico, Panama, Cuba, and Nicaragua, and he won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his service at Veracruz. He would add a second Medal of Honor a few months into the Haitian campaign at the Battle of Fort Rivière.

Within six weeks of the invasion, the US military controlled the country’s cities, they had installed a more pliable president, and Congress approved a “treaty” giving the US economic and military control of Haiti for 10 years. Eventually a garrison of more than 1,000 marines would occupy the island, and at times they would face stiff opposition from the revolutionary cacos, especially in the country’s rural regions. After the military tamped down opposition in late 1915, it spiked again in late 1918 and continued for two more years.

But the occupation dragged on beyond even the 10 years that Congress had authorized. In 1918, the US achieved one of its principal aims, rewriting the Haitian constitution to overturn the previous ban on foreign ownership of land (a document supposedly authored by then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt), yet American forces remained. The NAACP became a vocal critic of US policy after James Weldon Johnson visited the island and wrote an excoriating report on conditions there. As part of this national campaign to end the occupation, NAACP national secretary Herbert Seligman spoke at the Brooklyn Society for Ethical Culture on February 27, 1921, saying,

“The American occupants of Haiti can point to three accomplishments in this republic. First, the building of roads through the interior for the use of soldiers and transportation of ammunition. Second, the enlargement and improvement of civil hospitals, and lastly, the creation of the Haitian Gendarme, under the command of non-commissioned officers of the United States Marine Corps. Under these American officers a list of atrocities have been perpetrated which would make Americans blush to read aloud.”

The occupation became increasingly unpopular in the US and Haiti. One of the turning points was on December 16, 1929, when marines fired on a crowd that had gathered for a general strike in Les Cayes, killing 12 and wounding 23. Newly-elected President Franklin Roosevelt signed another “treaty” in August 1933 to begin the American withdrawal, and the last marines left the island on August 15, 1934, 19 years and 18 days after they first arrived.

The toll of the US occupation was steep. Estimates of the number of people killed during the fighting range between 15,000 and 40,000, the vast majority of them non-combatants. The US did make improvements to infrastructure, but mostly what the occupation did was reinforce the power of a small group of local elites, and the total control of the island’s economy and security by US interests.