On August 14, 1965, the Landing Platform Dock USS Duluth (LPD-6) floated out of Dry Dock No. 3 at the New York Naval Shipyard. In the preceding 145 years, this shipyard had witnessed the launch of 125 commissioned warships of the US Navy, beginning with the 74-gun ship of the line USS Ohio, and this would be the 126th – and final – to be built on Wallabout Bay.

Duluth was the last of six LPD’s built at the Yard, a program begun in 1959 with the Raleigh-class ships Raleigh, Vancouver, and La Salle, and followed by Duluth’s Austin-class sister ships Austin and Ogden. With Raleigh and Austin, like with so many ships before them, it was the job of the Yard to not only build, but also design a ship of a brand new class. This was often the job of the federally-owned Yards, to work out all of the design and production issues, and then pass off construction of later iterations of the ships to private shipbuilders.

The LPD’s would be a revolutionary new design, providing a capability to the Navy and the Marine Corps unlike any they had before. Building amphibious ships – ships designed specifically for delivering troops and equipment from sea to shore – was nothing new to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which had constructed eight Tank Landing Ships (LST’s) during World War II. These ships participated in landings in Italy and France, and they had the ability to drive up on the beach and disgorge heavy vehicles. LPD’s wouldn’t beach, but they had other important capabilities: a flight deck, to handle helicopters, a well deck, to launch small craft directly from the stern, and a huge capacity for equipment and supplies. They would be floating bases for up to 900 Marines to reach, secure, and hold the shore.

To design these ships, the Yard did not just turn to its naval architects, but reached out to its entire workforce. On July 31, 1959, the Yard newspaper the Shipworker published an appeal for cost-saving ideas in designing the LPD’s. Three weeks later, some of the suggestions were published, including reducing the number of partitions in the ship’s bathrooms. The Yard’s patternmakers also constructed a scale model of the ship to figure out how to assemble its frames, especially around the new well deck system.

With the completion of the Raleigh, the design was deemed a success, and it became the template for subsequent classes, including the slightly lengthened Austin, and even the modern San Antonios, which began to replace the earlier generation LPD’s in 2003. The launch of the Duluth represented the culmination of this program, and the ceremony’s keynote speaker was Vice Admiral John S. McCain, Jr., commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier (and resident of the Navy Yard’s Commandant’s House) and considered to be the father of the new amphibious doctrine. Just four months earlier, he had led the US invasion of the Dominican Republic, which was spearheaded by Marines embarked from USS Raleigh.

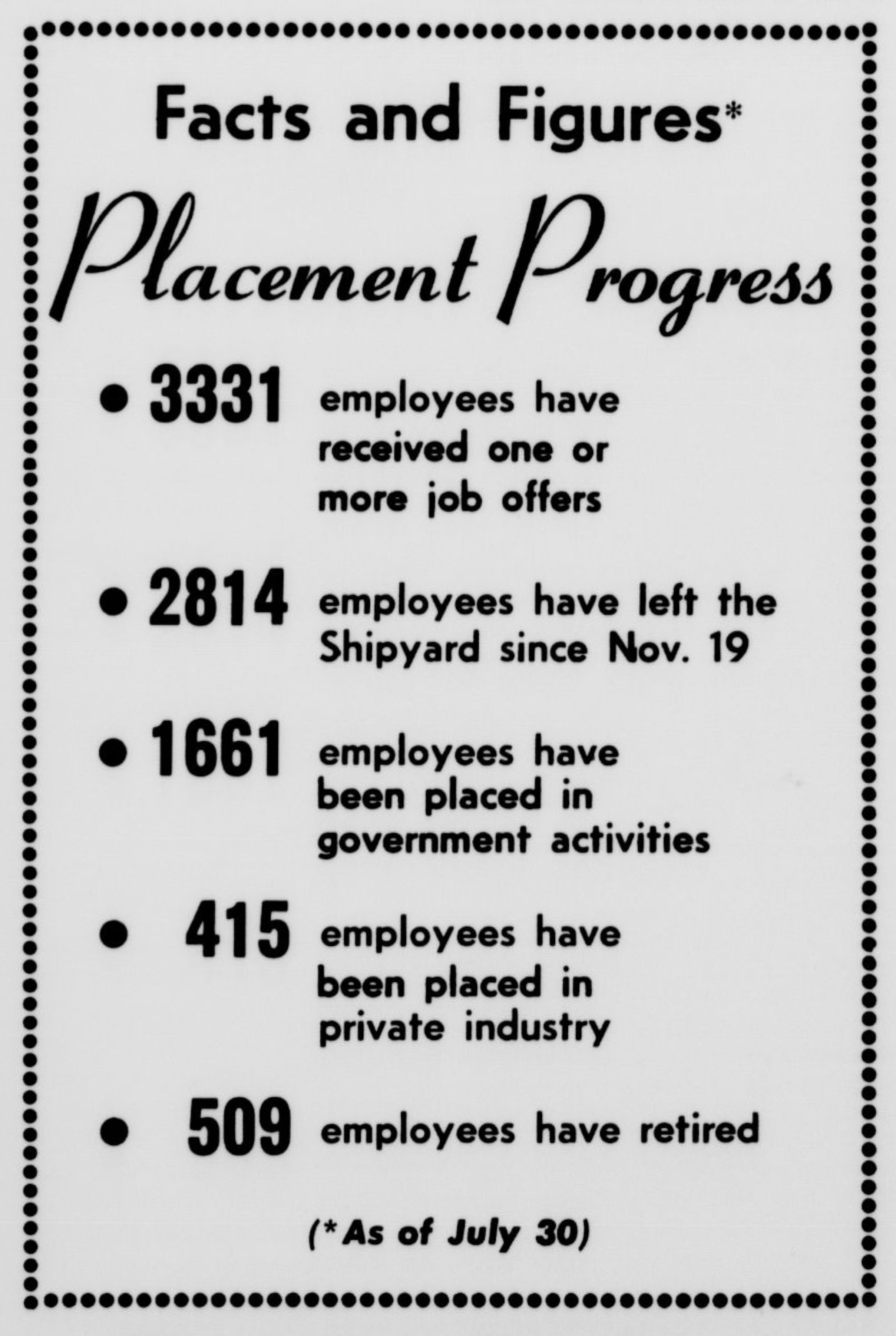

But between the keel laying of Duluth in August 1963 and the launching 20 months later, a huge change would rock the Yard and all of New York City: in November 1964, the Pentagon announced it would be closing the venerable Brooklyn Navy Yard. At the moment of the announcement, 9,600 civilians worked at the Yard (a number the current city-owned Brooklyn Navy Yard industrial park just surpassed for the first time). When the LPD contract was awarded six years earlier, it was thought that this would secure the long-term future of the shipyard. But a variety of factors led to the closure, including a greater reliance on private shipbuilders, concerns about safety after the Constellation fire in 1960, and the obstacle posed by the East River bridges to larger ships. By the time of the launching, the payroll was down nearly 3,000, with most workers taking assignments at other government facilities or opting for retirement. Within 10 months, employment would be zero.

So the launching of the Duluth was a bittersweet moment. While everyone cheered as Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s daughter Nancy Solomonson hit the bottle of champagne against the bow, they also knew it was the end of an era. Yard Commandant Read Admiral J.H. McQuilkin made sure to acknowledge Duluth as the product not of 20 months of work, but of generations of acquired skills and knowledge:

“Duluth’s construction is the culmination of the skills and crafts and workmanship gained in more than 164 years that this shipyard has been in existence. The result of this combination of talents is one of which we of the Shipyard are very proud and in which we believe that the Navy and the country can take equally justifiable pride.”

As the last Navy ship built at the Yard, it’s fitting that Duluth was one of the last Brooklyn-built ships still afloat. After 40 years of service, the ship was towed to Brownsville, Texas and cut up for scrap in 2014.