As I write this, the USS Slater, a World War II-era destroyer escort, is steaming its way (actually, being pushed by a tugboat) up the Hudson River back to its usual home in Albany. For the past 12 weeks, the Slater has been a visitor to New York City, laid up for repairs at Staten Island’s Caddell Dry Dock.

Since 1997, the Slater has been a been a museum ship, showcasing the important history of these humble vessels. More than 500 destroyer escorts were built in World War II, and Slater is one the last still afloat. But in order to continue to share the story of these ships and the men who served aboard them, Slater was in need of some repair work, including repairing the hull, interior spaces, and the anchor chain. The project cost roughly $1.3 million dollars, and probably would have cost a lot more were it not for the countless hours donated by volunteers (read about their work in the latest newsletter).

For most of its New York City stay, the Slater has been in dry docks at Caddell, which has six floating dry docks at the company’s North Shore facility. It was fitting that a historic ship should be worked on in an historic shipyard – Caddell is the oldest private shipyard in New York Harbor, in continuous operation (and family ownership) since 1903. While the Brooklyn Navy Yard (and its former annex in Bayonne) have the harbor’s only graving docks – basins for ship repair built on land – Caddell has the largest collection of floating dry docks. These are, essentially, ships in and of themselves, which can be lowered in the water and then raised underneath the vessel being repaired, bringing its hull completely out of the water (a process known as “fleeting”).

Perhaps the most dramatic (and awesome) change that these weeks of repair work brought was the ship’s new paint job. Rather than just repaint it battleship grey, the museum decided to return it to is World War II glory, decking it out in its Measure 32/3D “dazzle” camouflage paint job. Developed during the First World War, dazzle camouflage was not designed to conceal a ship from the enemy, but to make it very visible. With its many lines and polygons darting at various angles (and often very bright colors), enemy ships could see it, but had difficulty determining the ships’s direction, speed, and type. Though not as flashy as its predecessors (which often boasted colors that earned them the name “floating Easter eggs”), the refurbished Slater looks unlike anything afloat today.

But 70 years ago, Slater was not unique, but a member of a vast flotilla, essential weapons for keeping Allied shipping lanes open, especially in the treacherous North Atlantic. The destroyer escorts, or DE’s, were designed specifically for anti-submarine warfare, assigned primarily to convoy protection and coastal defense. Their role grew out of hard lessons learned first by the British, then the Americans, in the early days of the war.

Starting in 1939, British shipping was marauded by German U-boats around the world, threatening the lifeline of supplies to the besieged island. While Britain had mastered the art of the convoy in the First World War – sending merchant ships in large formations, ringed by warships to protect them from submarines – by World War II, they lacked adequate numbers of warships to properly protect them. In September 1940, the US and Britain signed the so-called “Destroyer-for-Bases” agreement, sending 50 mothballed World War I destroyers to Britain and Canada in exchange for bases in the Caribbean and Newfoundland. In March 1941, as part of the Lend-Lease agreement, Britain commissioned American shipbuilders to design and build a new class of cheaper, slower, lightly-armed vessels for convoy duty, and the DE was born.

Destroyer escorts could be built quickly and cheaply and still fulfill their important roles. While standard destroyers were built to rigorous Navy standards that demanded high speed and potent firepower in order to keep up with and protect the battleships and fleet carriers they escorted, this level of performance was not necessary for convoy duty. They only had to keep up with merchant ships, most of which traveled at 10-15 knots; and the U-boats they were chasing topped out at about 18 knots, and barely broke 7 knots when submerged. Though they lacked big guns and thick armor, their depth charges packed a punch, and they were deadly effective.

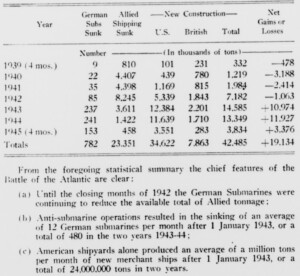

By the time America joined the fight in December 1941, we too found ourselves woefully unprepared to protect merchant vessels. In the first six months of 1942, German U-boats launched an all-out assault, sinking more than 400 vessels in American coastal waters. It was not until mid-1943 that the tide was turned against the U-boats, in large part due to the development of DE’s and similar vessels. With hundreds of ships carrying troops and supplies departing from North American ports every week, large numbers of escort vessels needed to be built. This new armada, coupled with air support, better radar, and superior tactics, not only protected the convoys, but actively pursued and sunk the U-boats in what were know as “Hunter-Killer Groups.”

The Slater served valiantly in the Battle of the Atlantic from her commissioning in May 1944 until the end of the war in Europe; she then transited the Panama Canal and fought in the Pacific, but her career in the US Navy ended soon after. Though celebrated for her role in World War II, the ship actually spent the vast majority of her working life in the Greek Navy, patrolling the Aegean Sea and serving as a training vessel for nearly 40 years.

With just a few more miles of Hudson to go, she will be back in her berth and ready to receive visitors again in the coming days, so we encourage you to go and check out her – and her new paint job (and like them on Facebook!) If you would like to learn more about the Battle of the Atlantic, convoys, and the role of the DE’s, join us July 3–5 for our Military History Tours of New York Harbor with Classic Harbor Line and the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, or join our World War II Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard on Sunday, July 6.

Turnstile Tours offers several tours that highlight New York’s waterfront, past and present. We offer our Past, Present & Future Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard every Saturday and Sunday afternoon, and other special themed tours of the Yard on select weekends. All tours are offered in partnership with and begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at Building 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the Yard’s history and a host of great special events and programs. We also give tours of the Brooklyn Army Terminal, offered in partnership with the New York Economic Development Corporation, two weekends per month.