February 15 marks the anniversary of one of the most dramatic and shocking moments in the Second World War, the fall of the “Gibraltar of the East,” Singapore, in 1942. While Singapore is very, very far away from the places that we give tours, we have a special connection to that country, and to the people there conducting scholarship on World War II history, an area of particular interest to us.

Turnstile Tours had the opportunity to travel to Singapore in October 2013, at the invitation of the Singapore Tourism Board and the National Heritage Board, where we led trainings for many of the country’s museums and attractions on how to make guided tours more engaging and interactive. One of the highlights of our trip was visiting the Changi Museum and meeting the team at Singapore History Consultants, Singapore Walks, and Journeys. This family of companies is in many ways a kindred spirit to Turnstile, for-profit businesses with a strong focus on research, education, and preservation. They operate many of the country’s World War II-related historic sites, but they also conduct an enormous amount of archival and archeological research to document and interpret this important history.

In a country as young (founded in 1959) and fast-changing as Singapore, the past is often paved over and lost in the scramble to build newer and higher. Through its museums, tours, research and restoration, this organization is doing tremendous work to educate Singapore’s residents and visitors about this painful and transformative period in the country’s history. Visiting the Changi Chapel, a re-creation of one of the makeshift chapels built by Allied POWs in the notorious Changi prison camp, was a powerful experience, and it is still a popular destination for veterans and their families. I also had the chance to tour the island on the Changi World War II Trail, visiting sites like the Kranji War Cemetery and Alexandra Hospital, site of one of the worst massacres during the Battle of Singapore.

Last fall, we were joined at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92 by Jeyathurai Ayadurai, director of Singapore History Consultants and the Changi Museum, for a lecture on the fall of Singapore. His talk greatly expanded our understanding of the war beyond the American experience, and we would like to share what we learned from his expert and engaging lecture.

As we’ve pointed out before, the events at Pearl Harbor were just one component of a multi-pronged attack by the Japanese to destroy British and American forces and capture their possessions across the Pacific region. In the span of just 12 hours, Japanese forces attacked American bases on Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam, and the Philippines, and the British came under attack at Hong Kong and Malaya.

Just as the US anticipated a war with Japan, the British had also made preparations for an attack on Singapore – in fact, they had been fortifying the island off and on for more than 20 years – but the strain of having already fought for more than two years in Europe left these preparations in tatters by 1941. World War I had greatly depleted the resources of the British empire and its formidable navy and allowed challengers to emerge, namely the United States and Japan. Unable to afford a three-ocean navy, Britain instead chose to develop the Singapore, or Swing Strategy. Should war erupt in the Pacific, a heavily-fortified Singapore would be able to hold out long enough – up to five months – for the main fleet to arrive from the Atlantic, which would then use the island as a base to recapture British territories and counter-attack (the strategy called primarily for a blockade of Japan to force a surrender).

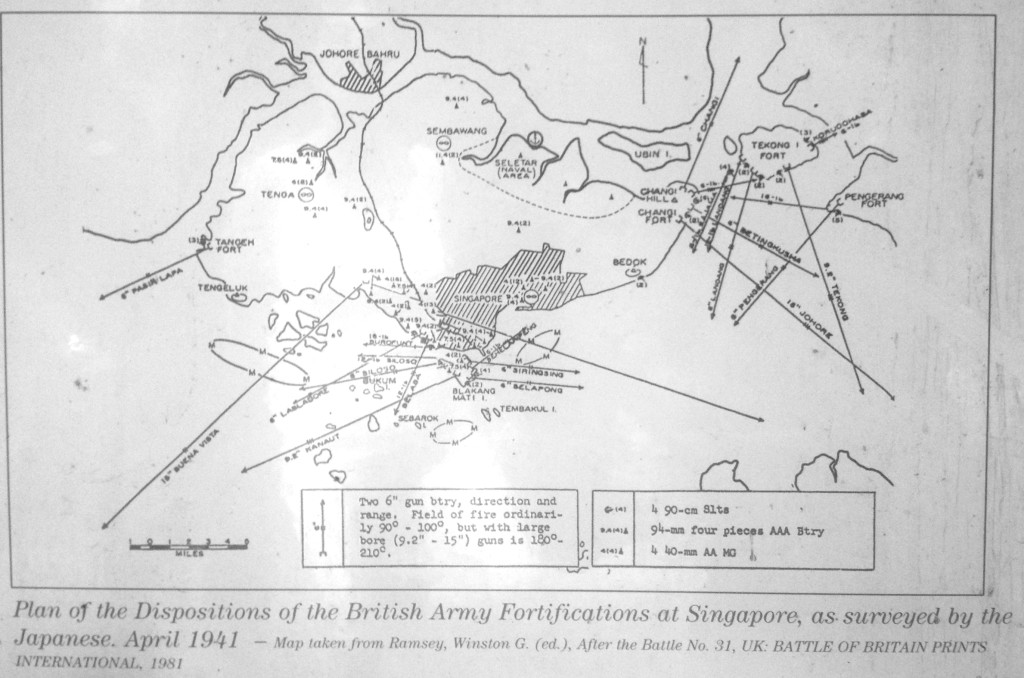

Singapore was in many ways a perfect location. Situated between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and right on the Straits of Malacca, one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, naval forces could easily reach Hong Kong, India, and Australia from there. But this strategy relied on building both a base that could accommodate a large naval fleet and fortifications and resources that would allow the city to withstand a protracted siege, as initial plans estimated it would take 42 days for the fleet to reach Singapore. So Britain began constructing the Sembawang naval base and the King George VI graving dock, on the north side of the island. To protect the city and the naval base, they relied on large fixed guns, concentrated on the eastern and southern shores, that could fend off any invasion force.

All of this planning relied on two critical assumptions: first, that Britain would not be engaged a simultaneous war elsewhere in the world, and second, that the enemy would attack Singapore from the sea, from the south end east. Both of these assumptions would prove incorrect, and lead to Singapore’s fall.

The first assumption unraveled in September 1939, when war erupted with Germany. Over the previous year, military planners had been increasing the relief time for Singapore from the initial 42 days to 180 days. By June 1940 and the fall of France, it would be changed again, to “indefinite.”

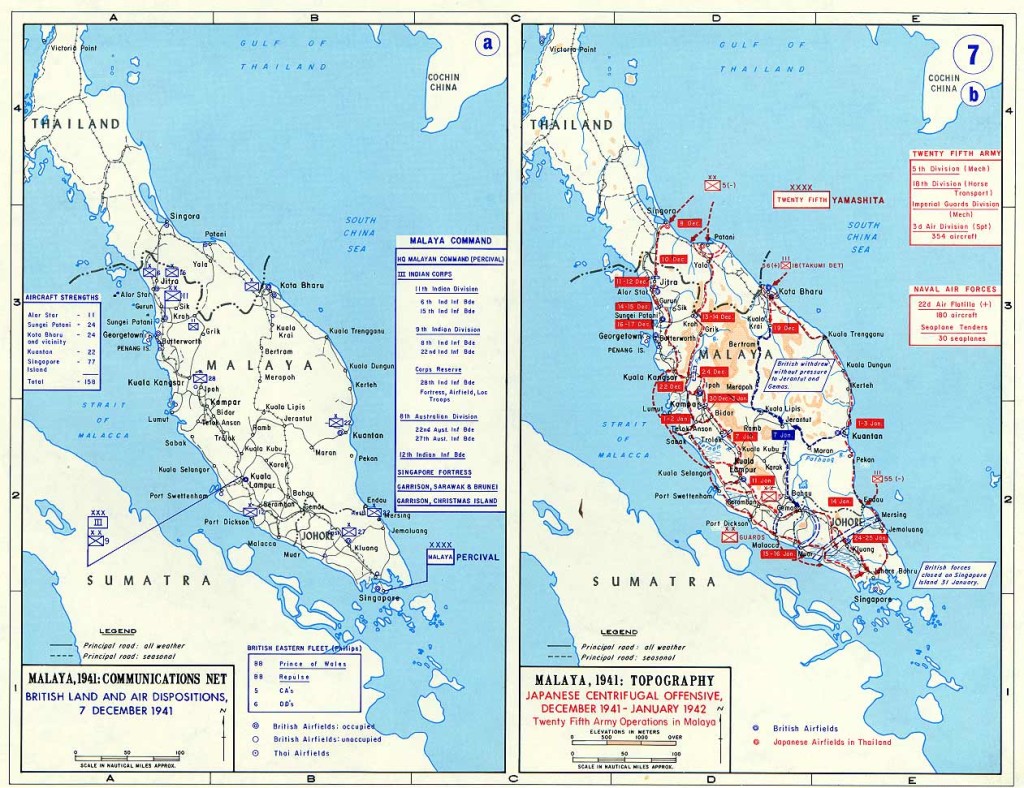

In 1920, when the Singapore Strategy was devised, protecting the island on the south and east made sense. The Malay Peninsula to the north was sparsely populated with few roads crossing the mountainous jungle terrain. No army could cross it and then mount a siege of the heavily-defended city. Instead, artillery would prevent any naval force from entering the Johore Strait separating Singapore from the mainland to capture Sembawang, the main prize. However, by the late 1930’s, many more roads had been built on Malaya, including along the remote east coast, providing an opportunity for an invader to reach Singapore from the north.

It would take more than just a few new roads to reach Singapore, however; it took also took a well-crafted plan and an audacious commander to carry it out. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita set an ambitious goal of reaching Singapore in just 100 days. Landing on the northern edge of the peninsula on December 8, 1941, lightly-armed, fast-moving troops, supported by almost complete air and naval superiority, routed British forces as they sliced through Malaya. Within 55 days, they stood across the Johore Strait from Singapore.

Britain had attempted a partial naval relief, sending a task force called Force Z. The battleship HMS Prince of Wales departed Britain on October 25 and arrived at Singapore on December 2 (a sailing time of only 38 days), after rendezvousing with the battlecruiser HMS Repulse in the Indian Ocean. The force was meant to be joined by the carrier Indomitable, but she ran aground in the Caribbean en route. Force Z was dispatched to the east coast of Malaya to intercept the invasion force. With no air support, either from the missing carrier or from the small and outdated RAF squadrons on Malaya, Force Z was quickly swarmed by Japanese aircraft. On December 10, 88 planes attacked the Prince of Wales and Repulse, sinking both and killing 840 sailors.

Without any naval or air support, Singapore sat alone, protected by 85,000 troops, composed of British, Australian, New Zealander, Indian, and Malaysian soldiers. Yamashita had only 36,000 troops, yet the Allied defenders and their commanders were overmatched. They possessed no tanks and few anti-tank weapons, as no one believed that an invader could get tanks through the jungles. Despite the lightning progress of the Japanese across Malaya, Singapore’s commanders refused to build fortifications in the north, believing it would undermine morale and spread panic. Singapore had also endured a constantly changing cast of squabbling, disorganized commanders; the last man holding the bag at the end, Lt. Gen. Arthur Percival, only took command in April 1941. He had rightly guesses as early as 1936 that an attack would come from the north, but he felt it would be the northeast, directly at the naval base and within range of the fixed guns.

On February 8, 1942, Yamashita commenced his attack, on the lightly-defended northwest of the island. Poor communication, and a misguided belief that the main attack would still come from the northeast (Yamashita’s diversionary buildups and feints in that area contributed to this illusion), led to the unraveling of the defenses. No reinforcements were sent to the northeast, and troops were withdrawn prematurely despite early successes repulsing the Japanese. With his troops on the run towards the central city in the south, and his main food, water, and ammunition supplies captured, Percival had no choice but to surrender or risk the destruction of the city and countless civilian deaths. After holding out for just one week, Singapore and its 80,000 defenders surrendered unconditionally, the largest surrender in the history of the British military.

Following the surrender, Singapore would endure more than three and a half years of Japanese occupation, and the POWs and their families would be subjected to horrible depravations, both at Changi and labor camps across Asia. Percival himself became a prisoner of war, freed only in August 1945. He, along with American Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, commander of forces that surrendered on the Philippines in May 1942, was invited by Gen. Douglas MacArthur to attended the official surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri on September 2. Percival and Wainwright flew to the Philippines the following day to attend the surrender ceremony there, where they faced the Japanese commander – Tomoyuki Yamashita. Percival refused to shake his hand.

We want to thank our friends at Changi for sharing their knowledge with us and helping to preserve this history.