War has played an integral part in the history of Prospect Park. In August 1776, the future site of the Park was a battleground, as American troops tried to stop the British advance in the epochal Battle of Brooklyn. Originally conceived in 1861, the Civil War intervened; this turned out to be a blessing, as the pause gave the Park’s commissioners reason to reconsider the original design – with Flatbush Avenue coursing through the middle of the proposed park – and instead hire the visionary team of Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted. 50 years into its life, World War I would arrive to alter the Park’s landscape yet again.

The world was engulfed in war for nearly three years before the US joined the fray, and it was in these early days in the fall of 1914 that the war would first come to Prospect Park – in the form of 90 zoo animals. In a London gripped by war, the Bostock Menagerie, a popular traveling zoo, was forced off its exhibition grounds, which were commandeered by the British Army. Rather than look for a new home, the zoo’s owner decided to sell off the whole lot, at cut-rate prices. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle got wind of this and decided to launch a fundraising campaign to purchase the animals. On October 18, the paper argued, “The war has given us the opportunity to buy the animals for one-third or one-quarter of what they are worth, and we are very foolish to not take advantage of it.”

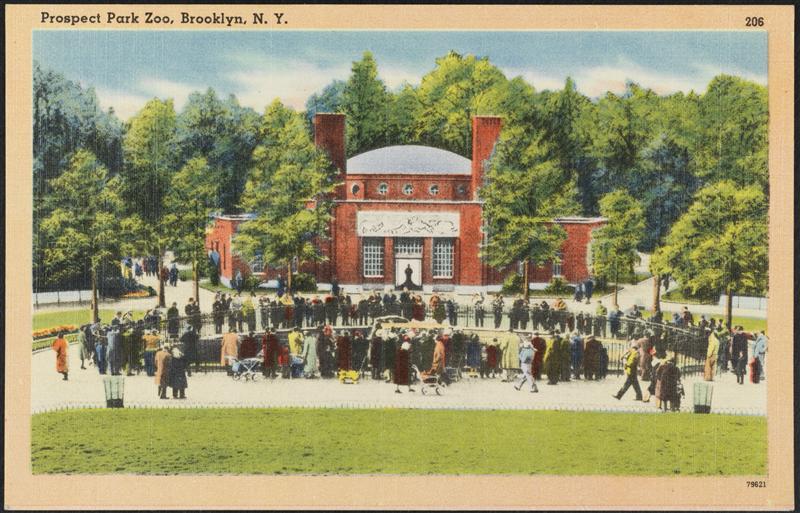

Prospect Park had a small zoo – a set of cages located on the top of Sullivan Hill in the northeast section – since 1890, but they had nothing as exotic as the lions, leopards, and monkeys on offer from Bostock. Within two weeks, the Eagle had raised the requisite $3,000, much of it in small donations from children, and the animals were loaded onto a ship bound for America. The voyage was not without incident; the ship ran out of meat for the animals, so one of the bears was shot and fed to the others (he was replaced with a bear loaned from the Bronx Zoo). One of seven lions on board managed to escape its cage in the ship’s hold and tried to pry open the monkey and mule cages for a meal, and, “it took nearly three hours of hard fighting to subdue the animal.” Though they had escaped Britain, the animals would not escape the war. A new zoo was constructed in 1915-16, but by the winter of 1917, the austerity of the war had forced the Park to economize, and they began feeding them “aged and useless horses” that were “secured by transfer from other departments.”

When America finally entered the war on the Allied side, for the first time in 50 years, the country had to raise a mass army. 2 million men were needed for the American Expeditionary Force that would be sent to Europe, 4.7 million would serve in uniform, and more than 24 million would register for the draft. This was compared to a peacetime army of just 128,000. Massive enlistment was needed, and parks and other public places were used extensively for recruiting young men and selling war bonds – perhaps most famous of these schemes was the USS Recruit, a wooden battleship constructed in the center of Union Square.

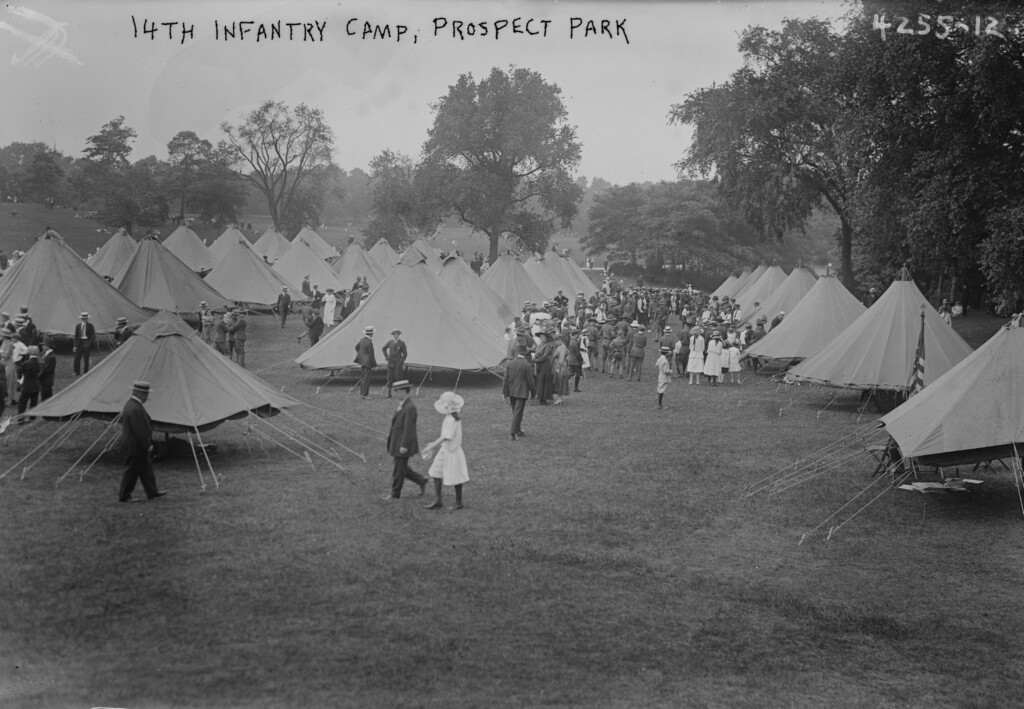

Prospect Park never had anything so colossal, but on June 30, 1917, the 14th New York Infantry Regiment – then-residents of the Park Slope Armory – built a temporary encampment on the northern end of the Long Meadow to draw volunteers. More than 60,000 people thronged the Park to see the soldiers and listen to a concert performed by John Philip Sousa’s Band and more than 5,000 Brooklyn schoolchildren, who were arranged to form an American flag (we haven’t been able to find a picture of this scene, but “living flags” were all the rage back then).

Overall, the war was not kind to Prospect Park, mostly because it sapped it of the money and manpower needed for basic maintenance. The Brooklyn Parks Department report for 1918 notes that, “Experienced park department laborers, climbers and pruners, and others, quit to obtain more remunerative pay in munition plants, shipyards, and various fields of United States Government.” This labor shortage could not have come at a worse time, as the Park required “a far heavier draft upon the services of our arboriculturists than had been made on that important branch of the department in several years was caused by the most destructive caterpillar pest in twenty years. Not only the parks but thousands of trees lining residential streets were attacked by the pests.”

Despite the diminished staff, Prospect Park did make important horticultural contributions to the war effort, as it was the site of an experimental “Model Backyard Garden,” the predecessor to the “Victory Gardens” of the Second World War. Visitors could come to the garden for advice on planting their own vegetables, and the Park distributed thousands of informational pamphlets on vegetable gardens. In 1917, more than 600 of these gardens were planted in backyards and vacant lots in Brooklyn alone. In the neighboring Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 94,000 packets of seeds were distributed, and children cultivated 409 small garden plots, which yielded $4,800 worth of produce in 1918.

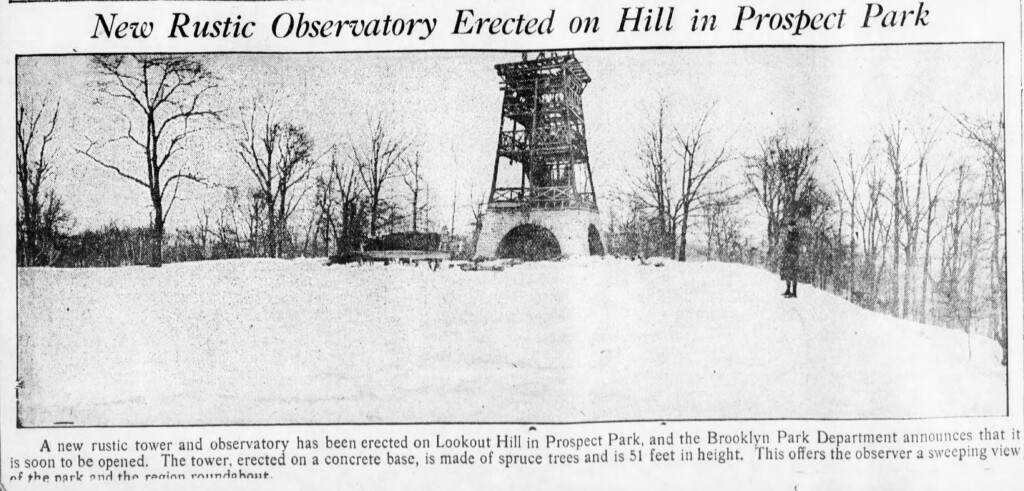

In addition to its temporary occupations for rallies, parades, and even baseball games, the military also took up a permanent residence in Prospect Park. The rustic tower on top of Lookout Hill, though incomplete, was opened in December 1917, a mere shadow of the regal stone structure proposed by the Park’s designers. But the following year, the tower was commandeered by the military to erect searchlights (though it’s unclear if it was ever actually used). Following the war, the structure was abandoned, and eventually torn down.

The Park also became an important site of commemoration. The nation’s first memorial to the war dead in a public park was unveiled on September 22, 1918, seven weeks before the war ended. 20,000 Brooklynites came to the dedication of the honor roll, located in the Concert Grove, and the 1918 Commissioners Report commented, “It is not an over-statement to say that never before in the history of Prospect Park had there been such a solemn gathering within its confines.” Plans were laid to build a permanent memorial, which was unveiled on June 21, 1921.

Unlike many other memorials of the era, which depict charging doughboys, Augustus Lukeman’s piece, located on the shores of Prospect Park Lake, is haunting, depicting the Angel of Death hovering over a soldier carrying a shattered rifle, turning towards Death as if in a trance. While the original honor roll bore only 356 names – the full scale of the carnage was not yet understood – the memorial now has more than 2,800. Originally donated by shipyard magnate William H. Todd (found of Todd Shipyards), the memorial had fallen into disrepair in recent years, but it was recently restored as part of the Prospect Park Alliance’s $74-million Lakeside project.