Yesterday the Brooklyn Navy Yard announced that they will be rolling out the first autonomous vehicles in New York City, which will provide a self-driving shuttle service inside the Yard’s gates. This exciting announcement inspired us to look back at the history of transit in and around the Yard. Poorly served by mass transit, getting tens of thousands of workers in and out of the Yard has been a 200-year struggle, but recent upgrades, and a willingness to experiment, have vastly improved the Yard’s transit connectivity in recent years.

Ferries

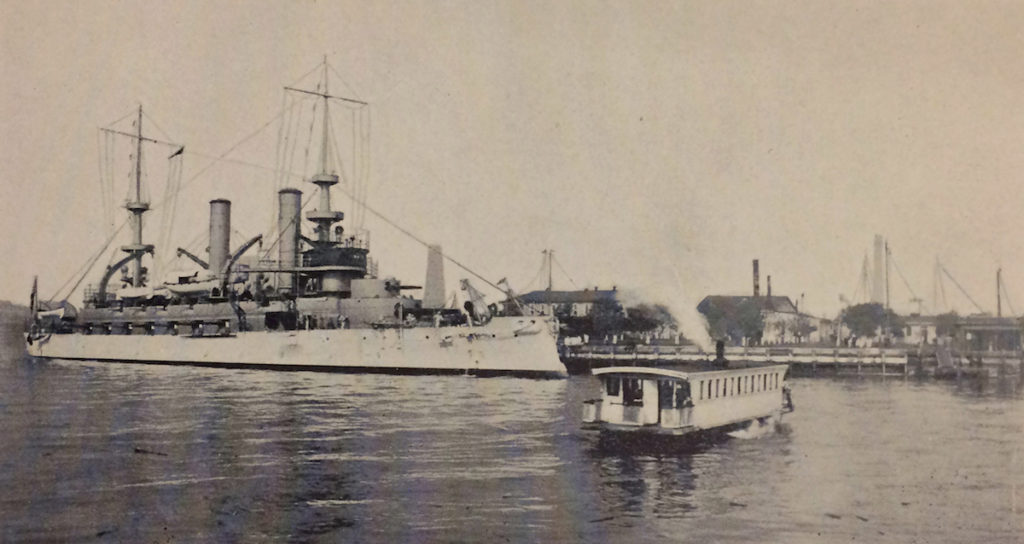

It makes sense that the first form of mass transit to the serve the Yard is the ferry. The first ferry route launched in 1817, linking Manhattan’s Jackson Street, then at the very center of New York’s shipbuilding industry, with the foot of Hudson Avenue, a short walk from the Yard’s main shipways, and it continued, with several interruptions, until 1870.

For much of its history, the Yard also had its own island, known as Cob Dock, which was a natural sandbar that over time was filled in and graded, home to barracks, coal and ammunition storage, and even a short-lived pigeon station. Launches a rowboats carried sailors back and forth, but the first permanent service was installed in 1880, when the chain ferry was built. A winch on land moved a chain that ran across the channel, pulling the ferry across. Originally powered by sailors turning it, they were then replaced by steam engine. The chain ferry was removed in 1910 after a causeway was built out to Cob Dock, and today the island is indistinguishable from the mainland, as the shoreline was completely reshaped during World War II.

Also during the war, the Navy built an annex to the Yard in Bayonne, NJ, to service larger ships that couldn’t fit underneath the East River bridges to reach the Yard, and there was regular ferry service between the two locations. A Staten Island Ferry, Washington Square, which crossed the Narrows to Bay Ridge, was pressed into wartime service in August 1942 and rechristened USS Staten. Service continued until 1947, when the ferry was sold and eventually scrapped.

And of course, the Yard is today the hub for NYC Ferry, serving as the homeport for the staffing, provisioning, and maintenance of the fleet. A new pier facility to dock all the boats in service is nearing completion, and starting in May, there will be direct service into to the Yard from Wall St-Pier 11 via the Astoria route ferry.

Trains

When you walk around the Brooklyn Navy Yard today, you may notice remnants of railroad tracks embedded in the pavement, which many people assume to be from a bygone trolley service. The Yard did have an extensive rail network, covering 30 miles of track at its peak in World War II, but it was entirely used for moving freight, not people. The Yard’s self-contained railroad moved raw materials, ship sections, and other components from workshops to assembly areas.

Starting in 1888, the Yard could be accessed from the Myrtle Avenue El, which ran from Downtown Brooklyn to the present-day M line. (This line was demolished in 1969, though a small section of it still stands one block east of Broadway.) The subway didn’t arrive in the vicinity of the Yard until the 1933, when the A train began running, and expanded in 1940 with the opening of the F, which are today the two most-frequently used lines for Yard commuters.

Trolleys couldn’t get you around inside the Yard, but they were one of the more popular modes of getting to work. Major streetcar lines ran along Park Ave, Vanderbilt Ave, and Sands St, and a line ran over the Brooklyn Bridge (which was removed in 1944). During World War II, with 70,000 workers in the Yard at its peak, city transit would route 63 cars per minute along these lines during the thrice-daily shift changes to move all the people in and out of the Yard.

But going long distances by streetcar was a slog. As the Yard grew, it drew a workforce from a much wider area, and it became a hassle for workers to have to switch from the subway to a streetcar or bus to reach the Yard. In November 1941, as the Yard was ramping up for war, the Yard Commandant wrote a letter to Mayor LaGuardia, noting the “unsatisfactory transportation and parking facilities available to employees of the Navy Yard.” “Not a single one of the primary rapid transit facilities of the city, either subway or commuting connections from Long Island and New Jersey, serves the Navy Yard directly. Employees using the primary rapid transit facilities must depend on secondary means such as street car, taxi, private car or walking to finally reach the Yard.”

With no plans to build a new subway line closer to the Yard, most people will continue to rely on “secondary means” to reach work, though efforts are being made to make that as hassle-free as possible. And though the last streetcars left Brooklyn over 60 years ago, the proposed BQX would connect the waterfront of Brooklyn and Queens, including the Yard.

Cars

If you open nearly any issue of the Navy Yard newspaper The Shipworker (published 1941–1966), you will find Yard workers complaining about parking. The busy shipyard simply did not have the room to store tens of thousands of private cars. Driving to the Yard became slightly easier with the construction of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, and the first section built was along Park Ave to ease truck traffic in and out of the Yard during World War II. The area underneath the expressway is today a municipal parking lot that was formerly reserved for Navy Yard workers.

Driving to the Yard today remains less than ideal, and workers are encouraged to travel by mass transit. With a workforce of 9,000, in addition to construction workers on several development projects, finding a parking space can be challenging. Though the new development at 399 Sands St, a mixed-use office and light manufacturing building, will have 430 spaces in a parking garage, there are no plans to build spaces for the cars of 10,000+ new workers that will be joining the Yard’s workforce in the coming years.

Bicycles

Bicycles have long been part of the Yard’s transportation landscape. In 1909, the Yard was supplied with a dozen bicycles for officers to get around the vast Yard and improve their physical fitness. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted “many points are far from the Commandant’s office … and much time is lost by officers in walking from one place to another.” In Jennifer Egan’s novel Manhattan Beach, a female shipworker rides her bike around the Yard, only to unceremoniously wipe out in front of a shipload of sailors (a real incident that happened to Audrey Lyons, who’s oral history is part of the Yard’s archive). Today riders still zip around the Yard, which is served by the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway bike path (and we offer bicycle tours of the Yard April–October!)

Innovation in cycling has continued at the Yard to this day. Before the rollout of CitiBike in 2013, the system was tested within the confines of the Yard for several months, and the Yard has also been a testbed for Seattle’s (now defunct) Pronto Cycle Share. As bike share systems move to technologies like dockless and electric-assist, the Yard is also on the cusp of innovation. Jump Bikes, which is currently pilot testing this system in the Bronx and Staten Island, is based in the Yard at New Lab, and they had been testing the system within the Yard for several months before they debuted on city streets last fall. Finally, the Yard last year hosted a beta test for OoneePod, a secure bicycle parking system that is now in the Financial District, with more coming soon to Atlantic Terminal and Queens Plaza.

Buses

Not everyone can get around by bicycle, which is why the Yard has had some form of internal shuttle bus system for more than 80 years. The first system started in 1940, when the Yard inherited the “auto train” that was used to transport visitors during the World’s Fair. The punishing schedule of the rapidly-expanding Yard quickly wore out these tourist trolleys, and they were replaced less than two years later by modern buses, which continued to serve until the Yard’s closing in 1966.

Other shuttles have served the Yard on and off over the years, but the current system was put in place in 2015, and last year they rolled out a new fleet of buses. The system operates on two loops, one going through the Yard and then to the High St and York St subway stations in Dumbo, while the other connects points in the Yard to the transit hub at Atlantic Terminal. Currently running Monday–Friday, 5am–10pm, the hope is to make it a 24/7 service for Yard workers. The system is free for riders, all you need is a Yard ID or visitor pass.

Which brings us to the latest innovation in Brooklyn Navy Yard transit, New York State’s first self-driving vehicles. Boston-based Optimus Ride will be operating a fleet of autonomous shuttles in the Yard starting this spring, to coincide with the arrival of NYC Ferry service. The vehicles will help move workers around the Yard, and deliver ferry riders who don’t have authorized access to the Yard to the security gates.

Part of the reason that the Yard can be a transportation innovator and host these types of pilot programs is because the streets of the Yard are outside of the jurisdiction of the city’s Department of Transportation. While all of its land and buildings are owned by the City of New York, the non-profit Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation is responsible for its operation and maintenance. While 200-year-old infrastructure can often be costly burden, it provides freedom to experiment outside the strict rules imposed on ordinary city streets. But it’s also because of the Yard’s commitment to innovation, especially in areas of smart infrastructure and community-oriented planning, and the amazing concentration of creative people and companies in the Yard community.