After a hiatus of 115 years, a vast squadron of homing pigeons has returned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

This weekend marks the opening of Fly By Night, an ambitious performance piece by artist Duke Riley and produced by Creative Time. On the deck of the decommissioned naval vessel Baylander, Riley and his team have erected a pigeon coop and assembled some 1,800 birds. After weeks of training and preparations, performances will begin on May 7 and run for six weeks, every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday night at dusk. Each evening, this flock will be released as the sun begins to set, each bearing an LED light on its foot to create a swirling, winged light show above the East River.

The piece is in many ways a culmination of many of Riley’s personal and professional passions, as he has had a long association with pigeons, seafaring, and the waterfront. A pigeon fancier himself, many of the birds in this show are of his own flock, while others have been borrowed or fostered from coops around the city. His 2013 project Trading with the Enemy involved training pigeons to fly from Havana to Key West, each laden with a contraband Cohiba cigar. In 2007, he constructed a replica of the Revolutionary War submarine Turtle, and attempted to reenact its unsuccessful attack run on a British vessel, this time approaching the cruise ship Queen Mary 2 (the stunt landed him in jail).

Brooklyn’s fast-disappearing industrial waterfront has a special draw for Riley, but the Brooklyn Navy Yard had a unique appeal for its important – if brief – association with the art of pigeon husbandry.

In the late 19th century, navies around the world faced a problem: their ships were getting ahead of their ability to communicate with them. The range of visual forms of ship-to-shore or ship-to-ship communication – semaphore, and later, Morse code with electric lights – was, at most, 7-10 miles. When ships struggled to travel faster than 7 knots, information about enemy vessels that were an hour’s sail away could be useful. But as ship speeds broke the 20-knot barrier, visual-range communication provided only a few minutes of advance notice, rendering it basically useless in high-speed naval battles.

Enter the homing pigeon.

Pigeons, and their unique ability to return to their home coop from distances of hundreds of miles, have been used for communication since ancient times, but it was only in the 19th century that their military usefulness was rediscovered. Not only could they travel far, but quickly, reaching speeds of 60 knots or more. Naval planners in the US and Europe saw the potential for pigeons to relay vital information from ships patrolling the coastline back to command posts on land. A mini-arms race erupted as militaries competed to breed the fastest, most reliable pigeons for their vast squadrons.

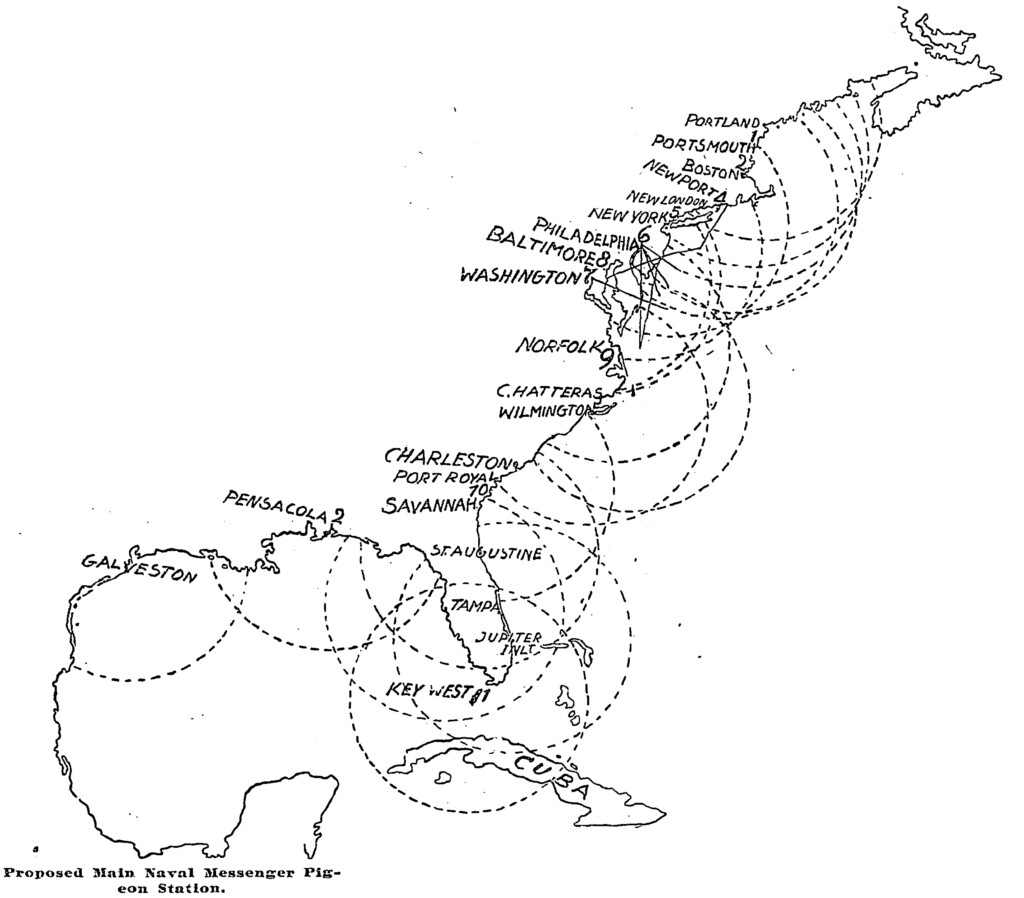

In 1896, the US Navy began establishing pigeon stations along the coast, including at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Yard’s coop was constructed on Cob Dock, an artificial island in the center of Wallabout Bay – it no longer exists, as it was dredged away during World War II to make way for a huge expansion. Though we possess many dozens of maps of the Yard, we have not been able to find any that pinpoint the pigeon station, but Cob Dock was also home to the ordnance storage area, firing range, coal storage, and receiving ship for newly-enlisted sailors. The initial Brooklyn flock was made up of about 60 pigeons, almost all of them bred at the station in Key West, Florida.

Much hope was pinned on these pigeons, that they would provide the missing communication link to knit together America’s coastal defenses. In an exhaustive 1897 report on naval pigeons written in Proceedings of the US Naval Institute, Lt. E.W. Eberle wrote:

In protecting our coast our strength lies in concentration of forces; our fighting ships are too few in numbers to be divided; we must keep them together in order to be able to strike a powerful, decisive blow, and here is where the scouts, with their swift-winged little messengers, stand out in such importance, because the scouts are the ones that furnish the fleet with the information which tells when and where to strike with the death dealing right. A fleet without scouts is like an army without cavalry.

Eberle, like many military thinkers at the time, had a very narrow view of the role and potential of the Navy, as it lagged behind the Great Powers of Europe. The Navy was largely confined to coastal defense, and many feared that America was vulnerable to seaborne attack from Britain, France, Germany, or Spain. But America, and the entire world, was on the cusp of a naval revolution that would bring about rapid innovation in technology and strategy. Within a year of writing those words, the Spanish-American War would put the US in possession of an empire stretching from the Caribbean to the Philippines. All of a sudden, the Navy was forced to shift its thinking from this near-shore “green water” strategy to a global “blue water” one.

While Eberle argued that pigeons were an essential component in naval strategy, it’s worth nothing that the most influential naval thinker of this period – and likely still to this day – Alfred Thayer Mahan made no mention of pigeons in his voluminous major works. He apparently could not see a role for the birds in his vision of the global ocean-as-maneuver-space for the Navy.

In the context of this sea change, the pigeon was really only a stop-gap solution to the Navy’s communication problems. They could not span the vast distances of an ocean, and they would not fly at night (a limitation that Riley has had to overcome), and while they were miraculously skilled at returning to fixed points on land, pigeons had trouble navigating between two moving ships, limiting their usefulness for ship-to-ship communication. They were just not very effective at networking a naval fighting force operating far from America’s shores.

The Navy had to look instead for a beyond-the-horizon technology, which they found in the wireless radio.

In May 1901, the Navy announced plans to discontinue the use of homing pigeons in favor of radio, just five years after the program started, and they began shuttering its coastal coops. The Brooklyn Navy Yard station possessed over 200 birds at its peak, but on December 30, they were all sold off, as were a combined total of more than 800 birds at the stations at Key West, FL, Portsmouth, NH, Norfolk, VA, and Newport, RI. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported:

Considerable sentiment was expressed at the pigeon house on cob dock this morning over the sale of the birds. The breeders and flyers have become the favorite pets of the sailors on the dock, who have been accustomed to pet them and to see that they are well fed. The prospect of their being removed was not, therefore, very pleasing to the jacks, many of whom spent part of the forenoon at the cote, bidding the birds goodbye.

The Eagle added, coldly, “The fact is that the birds have been of little practical use at the yard for considerable time, as they have not been able to compete with the progress of science.”

The closure of the pigeon stations was by no means the end of the pigeons’ military, or even naval careers. While the Navy began installing radios in ships in 1902, these sets were enormous and complex, and would remain so for years to come, so they would not fit aboard smaller vessels or the Navy’s burgeoning fleet of aircraft. Well into the 1930’s, Navy pilots and small craft carried pigeons with them to send out distress signals if they got into trouble. Though pigeons played little or no role in the Navy through World War II, the rating of “Pigeoneer” would persist until 1961.

Meanwhile, the Army found countless uses for pigeons for decades to come, as radios would remain heavy, cumbersome, power-hungry, and their signals easily intercepted, making them impractical for use by infantry. Pigeons were invaluable in the front lines of World War I, serving as not only messengers, but reconnaissance photographers and artillery spotters. In fact, the pigeons proved their worth so well, the Navy reconsidered their opinion of them during the war.

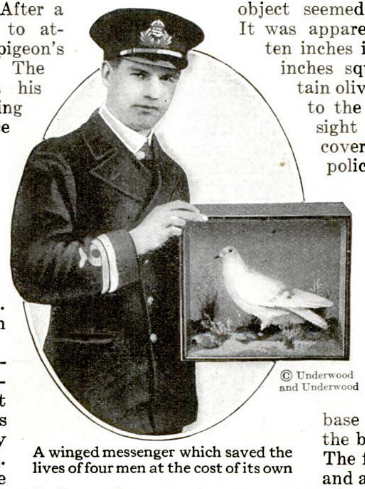

Easily America’s most famous pigeon was not a Navy, but an Army bird. Cher Ami, who was credited with saving 194 men of the “Lost Battalion,” survived losing an eye, a leg, and being shot through the breast on her 25-mile journey to bring word of the besieged unit’s position. The Croix-de-Guerre-winning bird is now stuffed and on display in the Smithsonian.

During World War II, 54,000 birds served in the Army, mostly for emergency communications, and interestingly, the main pigeon station was not too far from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, in Monmouth, NJ (watch this amazing video of this pigeon station from the 1930’s). That had been the resting place of World War II’s most decorated American pigeon, G.I. Joe, until the closure of Fort Monmouth in 2011 – she is now likely somewhere in the vast, secret Army archive at Fort Belvoir, VA. The US Army Pigeon Service was discontinued in 1957.

Fly By Night is an homage to many things – the waterfront, the sea, the Yard, but especially the birds. The story of the Navy pigeons is an important part of this show, but so too is the story of civilian pigeon keeping in New York City, a once ubiquitous pastime that is disappearing with the aging of fanciers and the encroachment of posh real estate that has no tolerance for rooftop coops.

While radios banished the pigeons from the Brooklyn Navy Yard 115 years ago, affection for these amazing creatures – like that displayed by the Navy “jacks” in 1901, and by the thousands of ordinary New Yorkers who keep this practice alive – has brought them back.