The Essex Street Market opened for business on the morning of January 9, 1940 in what the New York Times described as, “one of the shortest dedication ceremonies on record.” Beckoned by the celebratory music of the Parks Department band, a crowd of over 3,500 residents gathered on this blustery winter morning out front of the newly-built market for the 15-minute ceremony.

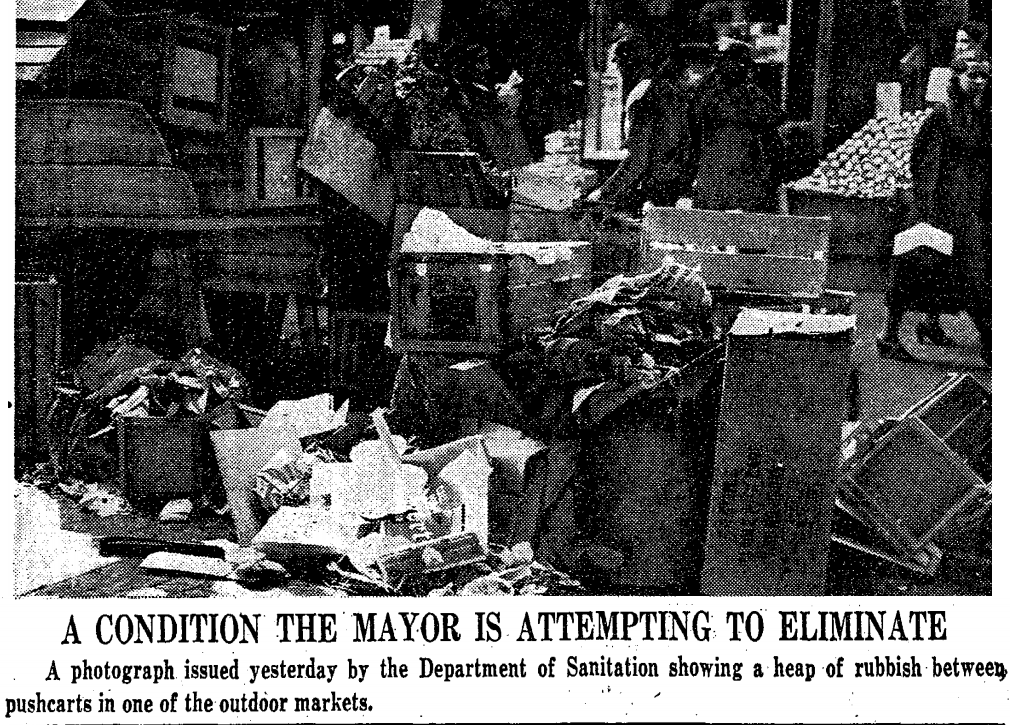

The construction of the market, and others like it across the city, was part of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia’s so-called “war on pushcarts”; he believed that street vending was “antiquated,” “unsanitary,” and “creating traffic congestion,” as he noted in an open letter to civic organizations in 1938. At the opening of the Essex Street Market, he continued this theme, warning that, “the city was not going to spend thousands of dollars [on new public markets] and allow pushcarts on the streets.” Following the ceremony, the crowds rushed into the market as the mayor made his rounds, putting a spotlight on vendors who had previously operated pushcarts on the streets of the Lower East Side.

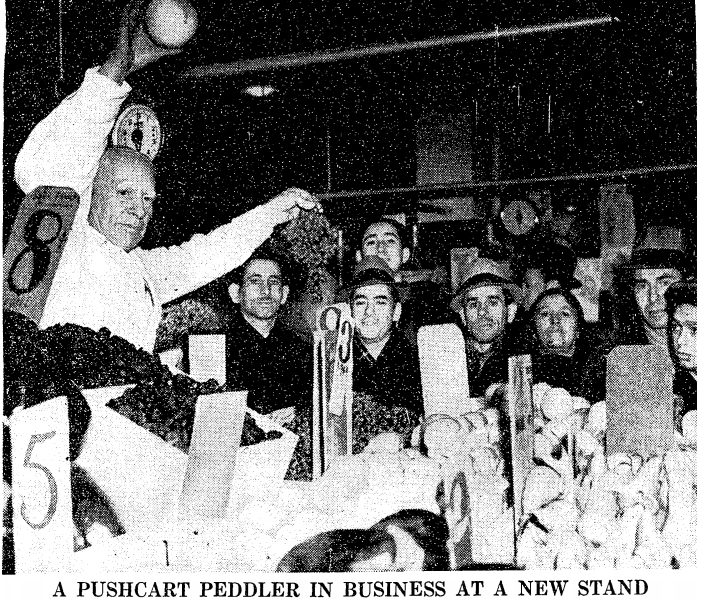

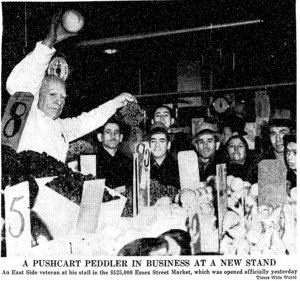

At the time of the opening, the Essex Street Market consisted of four buildings that stretched across three blocks of Essex Street between Broome and Stanton Streets. Built at a cost of $525,000 on land that had been cleared of tenements just over a decade before for the construction of the subway, the market initially leased stalls to 475 vendors, most of whom had been peddlers on the streets and at the open-air markets of the Lower East Side. Each paid $4.75 per week in rent for their new market stalls. Essex Street was the fourth of what would eventually be nine enclosed public retail markets in New York City, proceeded by the Park Avenue Enclosed Retail Market in East Harlem (1937), the First Avenue Enclosed Market (1938), and the Thirteenth Avenue Retail Market (1939) in Borough Park, Brooklyn.

While enclosed public markets were new to New Yorkers, city-operated markets had been around for a while. In fact, the now-defunct city Department of Public Markets had been established in 1917, as part of the New York State Food and Markets Law. This department had overseen the implementation and operations of a complex food distribution system in New York City, including wholesale and terminal markets, and a network of what were called “open-air markets,” many of which were located underneath the city’s bridges, where licensed pushcart vendors and farmers sold their products from stands rented from the city.

By the mid-1930’s, however, Mayor LaGuardia’s administration took the position that the licensed open-air markets were doing little to solve what they perceived as a “pushcart problem” – street peddlers, they felt, were poorly regulated and posed hazards to public health and safety. They set out to identify areas with the highest concentration of peddlers, licensed and unlicensed, with the intention of replacing them with indoor markets, while simultaneously decreasing the number of pushcart permits available. This policy had a significant impact on the residents of neighborhoods like the Lower East Side and Harlem, where pushcart vendors had clustered in tenement districts. Between 1934 and 1941, the city closed over 40 open-air markets, bringing the total down to 15 from a high of 56, and the number of permits issued to peddlers declined to fewer than 1,000 from 4,934.

The city’s Department of Markets report from 1940 downplays the challenges of moving street peddlers indoors: “[T]he removal of some 700 pushcarts from widely scattered areas on the Lower East Side and their enclosure in the centrally located Essex Street Market, partook of the nature of a major surgical operation.” With thousands of licensed and unlicensed vendors in the neighborhood, and only 475 market stalls available, street vending never completely disappeared from the streets of the Lower East Side, even if permits were scarcely available and ordinances prevented peddlers from selling their wares within 500 feet of the public markets. By the post-World War II period, the Department of Markets once again increased the number of pushcart permits, realizing that both street vendors and enclosed public markets had unique roles to play in making fresh and affordable food available to city residents, and street vendors continue to this day to be an important part of the city’s streetscape.

Today, the Essex Street Market occupies only one of the original buildings, located along Essex Street between Delancey and Rivington Streets, and still operates as a city-owned market with a mission to serve the local community. Then as now, there are vendors inside the market who are fishmongers and butchers, bakers and produce purveyors. Most of the stalls today are run by immigrants or the children of immigrants, hailing from places like Uzbekistan, Korea, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic, a continuation of its legacy as a marketplace that reflects the community that surrounds it. But unlike in the 1940’s, when most vendors were selling produce and groceries, today there is a wide range of prepared foods available, including chicken mole tamales, Japanese vegan and gluten-free bento boxes, spinach pies, tilapia sandwiches, grilled cheese, soups, cakes, cups of coffee, and chocolate truffles (see all the vendors here). You can even stop into the market for a haircut.