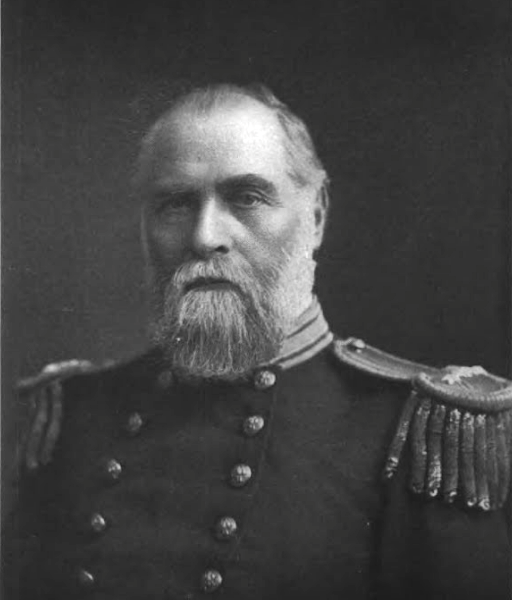

Peter Christian Asserson (1839–1906)

The Brooklyn Navy Yard has always adapted to change. Over its first 165 years, rapid changes in naval ship designs forced the adoption of new shipbuilding technologies, materials, and techniques, and the construction of new facilities. No single person did more to shepherd the Yard through these transitions than Peter Christian Asserson, civil engineer of the Navy Yard from 1885 to 1901.

Asserson (also sometimes spelled Assersen) was born in Eigersund, on Norway’s southwestern coast, in 1839. Like other people on this list, he left home as a teenager for a life at sea, signing on to merchant ships. He moved to the United States in 1859, arriving in New Orleans, where he took up civil engineering and assisted in the construction of lighthouses and other navigational improvements in the Gulf of Mexico. With the outbreak of the Civil War, he decided to head north, eventually landing in New York, where he enrolled in the Cooper Union to further his engineering studies.

Asserson enlisted in the US Navy in 1862, where he entered as a master’s mate, due to his extensive seafaring experience. Among the many ships he served on was the USS Supply (which had a notable visit to the Brooklyn Navy Yard a few years earlier), and he eventually took command of his own gunboats, participating in many major naval engagements of the war. In 1869, he was discharged from the Navy, but his service did not end there; as a civil engineer in private practice, he spent the next four years working to repair the war damage done to waterways and harbors in Virginia. In 1872, he returned to the Navy with the rank of captain, becoming one of the first uniformed civil engineers in the service and overseeing construction at the Norfolk Navy Yard. In 1885 he was assigned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

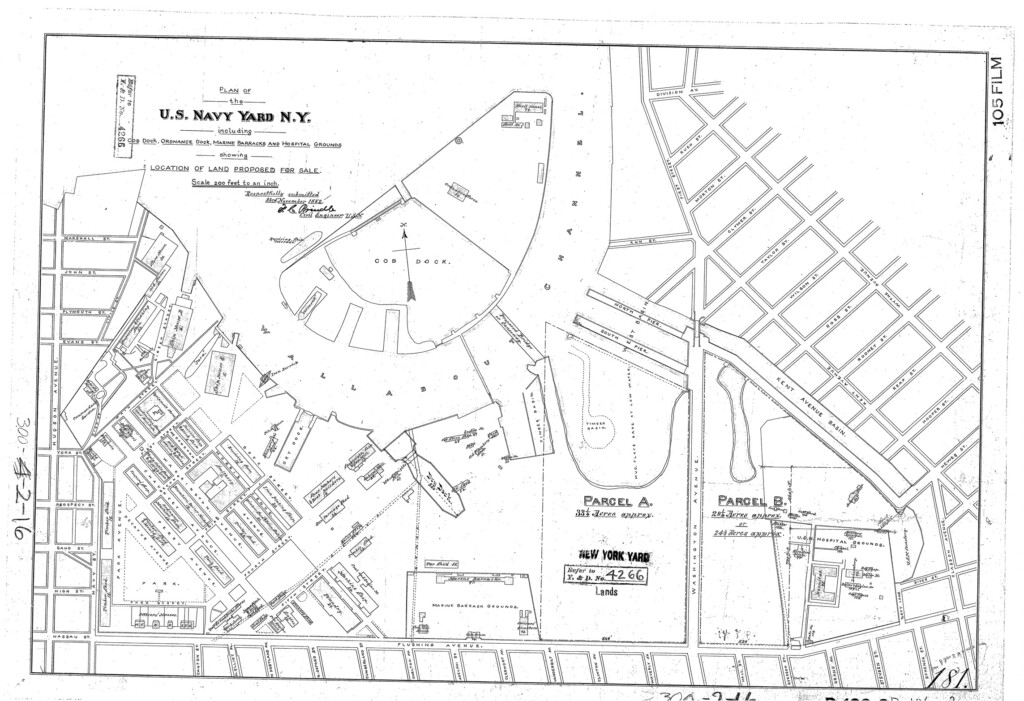

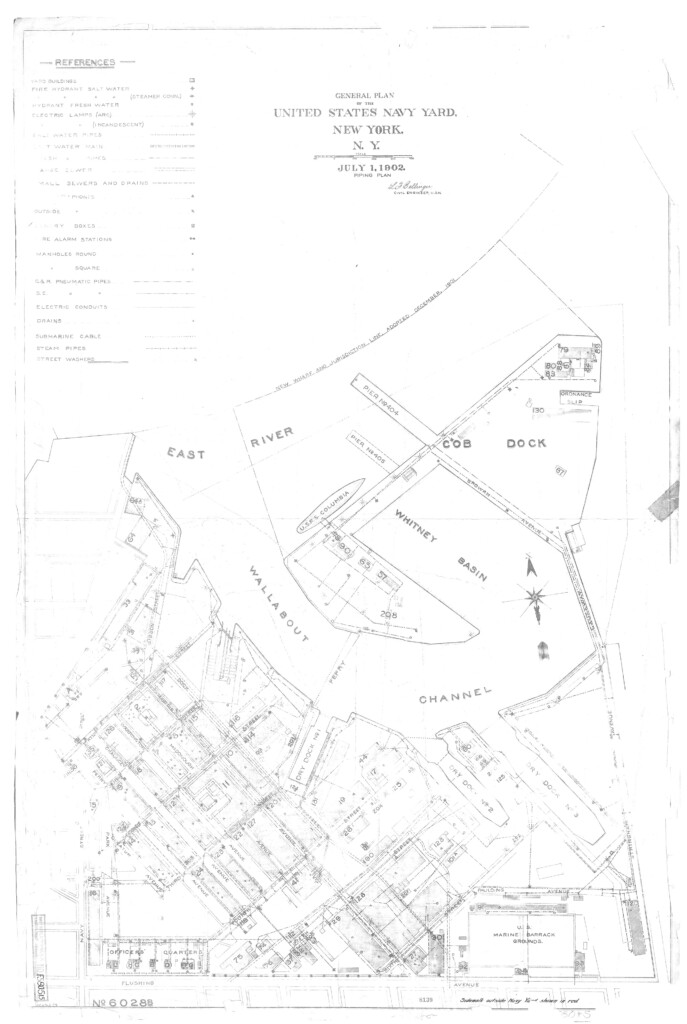

Comparing the two maps below, the first from 1882 and the second from 1902, you can see the enormous changes that Asserson oversaw during his 16 years at the Yard. He got to work very quickly, requesting $1 million for improvements, and continued to be a tireless advocate for resources for the Yard. Among the improvements were installing electric lights, building a Yard-wide railway network connecting the workshops for moving the increasingly-large components, and adding new piers. Cob Dock, the artificial island located in Wallabout Bay, had long been a site for coal and ordnance storage, receiving barracks, and firing ranges. With the advent of modern battleships, the center of the island was removed to expand the Whitney Basin, which could accommodate these new steel ships, like the USS Connecticut, flagship of Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet. To allow the construction of these larger ships, Asserson also tore down the antiquated shiphouses – essentially large barns constructed over the inclined ramps that ship hulls were built on – and replaced them with modern launchways with steel scaffolds. And for the fabrication of steel components, a massive new machine shop was built, Building 128, located at the bottom center of the 1902 map, and today’s Green Manufacturing Center.

But Asserson’s main area of expertise was in dry dock construction. When he arrived at the Yard, it had only the 350-foot Dry Dock No. 1, completed in 1851, and the 500-foot Dry Dock No. 2 was under construction. If the United States wanted to build a modern steel-hulled Navy, these facilities would need to be upgraded and expanded for longer, heavier ships. Dry Dock No. 2 was designed in wood, but this construction soon proved to be inadequate, and it was rebuilt with concrete a few years later. Dry Dock No. 1 was also improved, replacing its wooden caisson with a steel door. Dry Dock No. 3 could accommodate ships of more than 600 feet, and it would be officially completed in 1897 , but not without controversy. Soon after construction was done, the dock developed a substantial leak, prompting a series of courts-martial of Navy engineers for “carelessness, negligence, and inefficency,” though Asserson was not charged. During the first years of his tenure at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Asserson was not technically the chief engineer, but rather an assistant, though he was the principal manager for many of these construction projects. With the death of the official chief civil engineer Henry S. Craven in 1889, Asserson rose to this chief post, and attained the rank of Rear Admiral.

Asserson finished out his Navy career at the Yard, retiring in 1901, and he passed away just five years later. He left behind a long legacy of military service. In 1917, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that every single one of his progeny over age 16 were in military service – three sons, two sons-in-law, six grandsons, and even his granddaughter Marguerite enlisted as a Navy Yeomanette, a precursor to the famous Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) of World War II. Both his son-in-law and grandson, both named William B. Fletcher, rose to the rank of Rear Admiral, with the younger winning the Silver Star and Bronze Star in World War II and becoming a leading authority on amphibious warfare.