Times of war have always brought the biggest transformations to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and none were bigger than those that took place during World War II. But long before the attack on Pearl Harbor plunged America into the global war, US military planners saw the need to expand the country’s navy in order to fight on two oceanic fronts. A larger navy required larger facilities not just to build ships, but to outfit, service, and repair them. In short, the navy needed more dry docks in more places around the world.

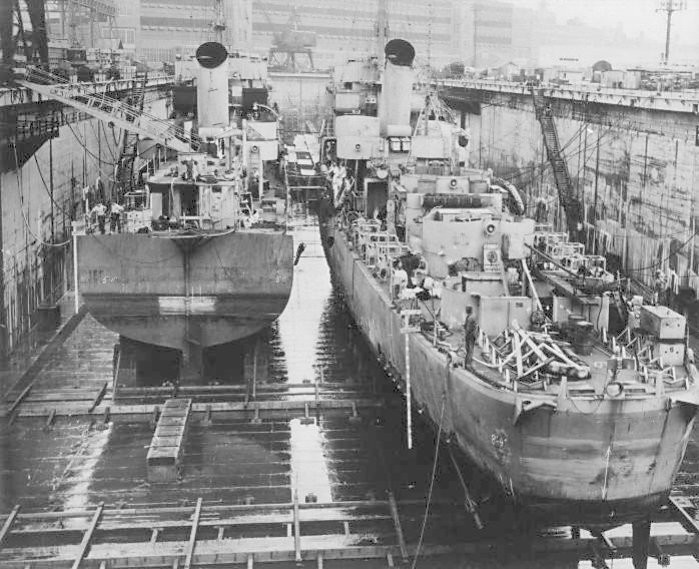

Now, for those of you who don’t know what a dry dock is, it’s basically a large, sunken basin with a door at one end that functions much like a canal lock. When filled, the water level is the same as the surrounding water, allowing a ship to drive into it. Once the ship is in position, the door is closed, the water is pumped out, and the ship can settle high and dry into a pre-fabricated cradle so that its underside can be worked on. As vessels have grown in size, dry docks have had to grow accordingly to accommodate them.

Beginning in 1938, the Navy embarked on an ambitious plan, conceived by the Commissioner of Yards and Docks Ben Morreel, to expand government-owned navy yard facilities to build and service a two-ocean fleet. [1] In the interwar period, naval technology and tactics had changed dramatically. The super-dreadnoughts of World War I, thought to be the pinnacle naval design, were now dwarfed by the new North Carolina– and Iowa-class battleships. But more importantly, aviation was replacing artillery as the real source of naval power – something the coming war would prove beyond a doubt – and America was racing against Japan to build a fleet of massive aircraft carriers. Yet the federal government had failed to invest in its navy yards, leaving them woefully inadequate to serve these modern behemoths.

Still confused? Watch a video of the World War II-era aircraft carrier and museum ship USS Intrepid enter the dry dock at Bayonne, NJ for maintenance in 2009. This dry dock is the exact same dimensions and design as dry docks 5 and 6 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Then watch a video of a ship coming out of dry dock – this time it’s the hospital ship Africa Mercy.

While the focus of Morreel’s plan was to expand yard facilities on the west coast and Hawaii to prepare for war with Japan, the long-established yards of the Atlantic coast also received heavy investment. The Brooklyn Navy Yard was allotted $15 million to build two new dry docks, expand another, and construct an annex and dry dock across the harbor in Bayonne, NJ. This expansion would transform the yard into the busiest ship repair facility on earth during World War II, when it serviced more than 5,000 vessels from the American and Allied navies; not to mention it also built two heavy landing craft, three battleships, and four aircraft carriers – the latter actually being built in the new dry docks (here’s an image of the yard crowded with ships being built and repaired in December 1944) – over the course of the war.[2]

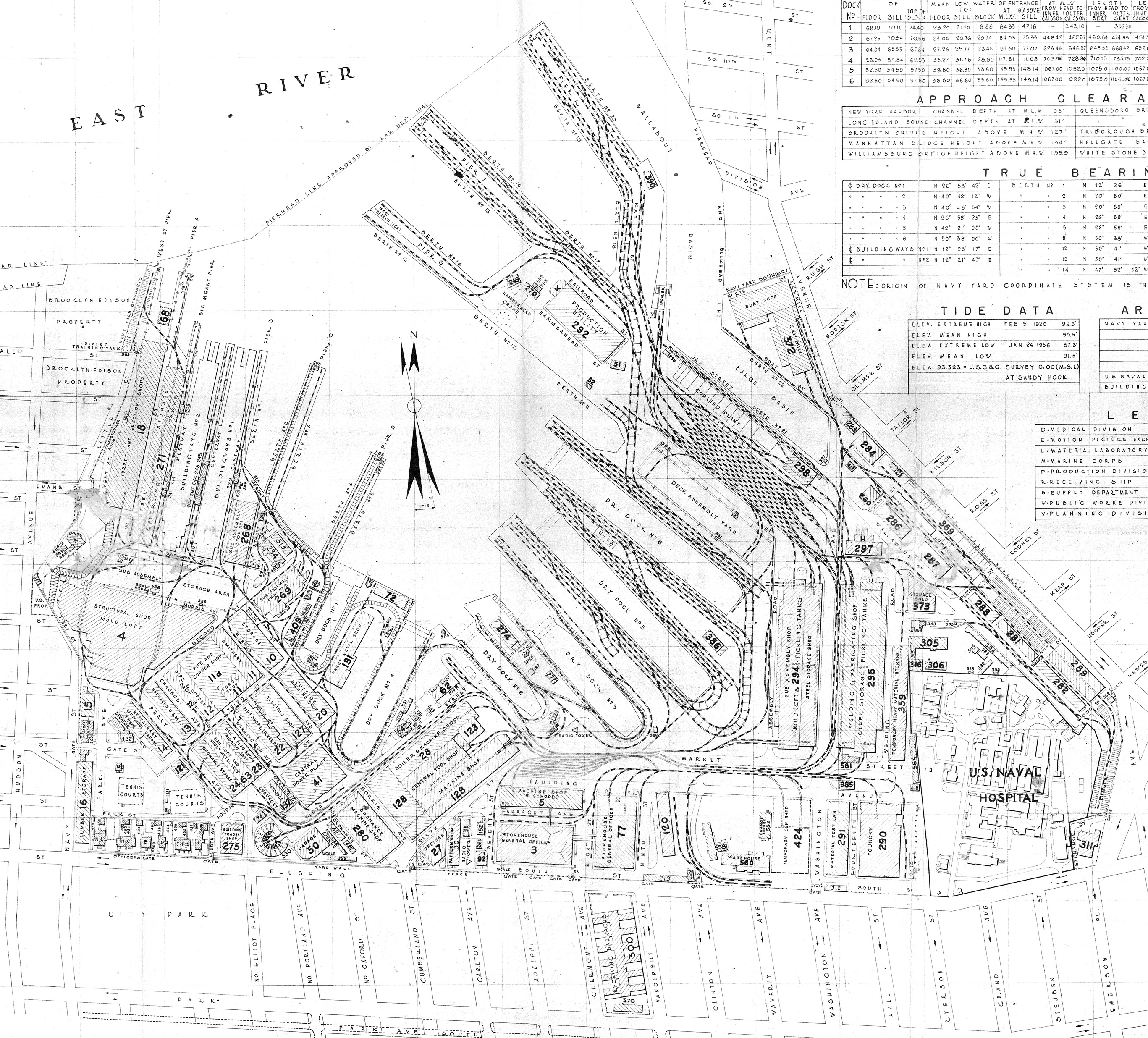

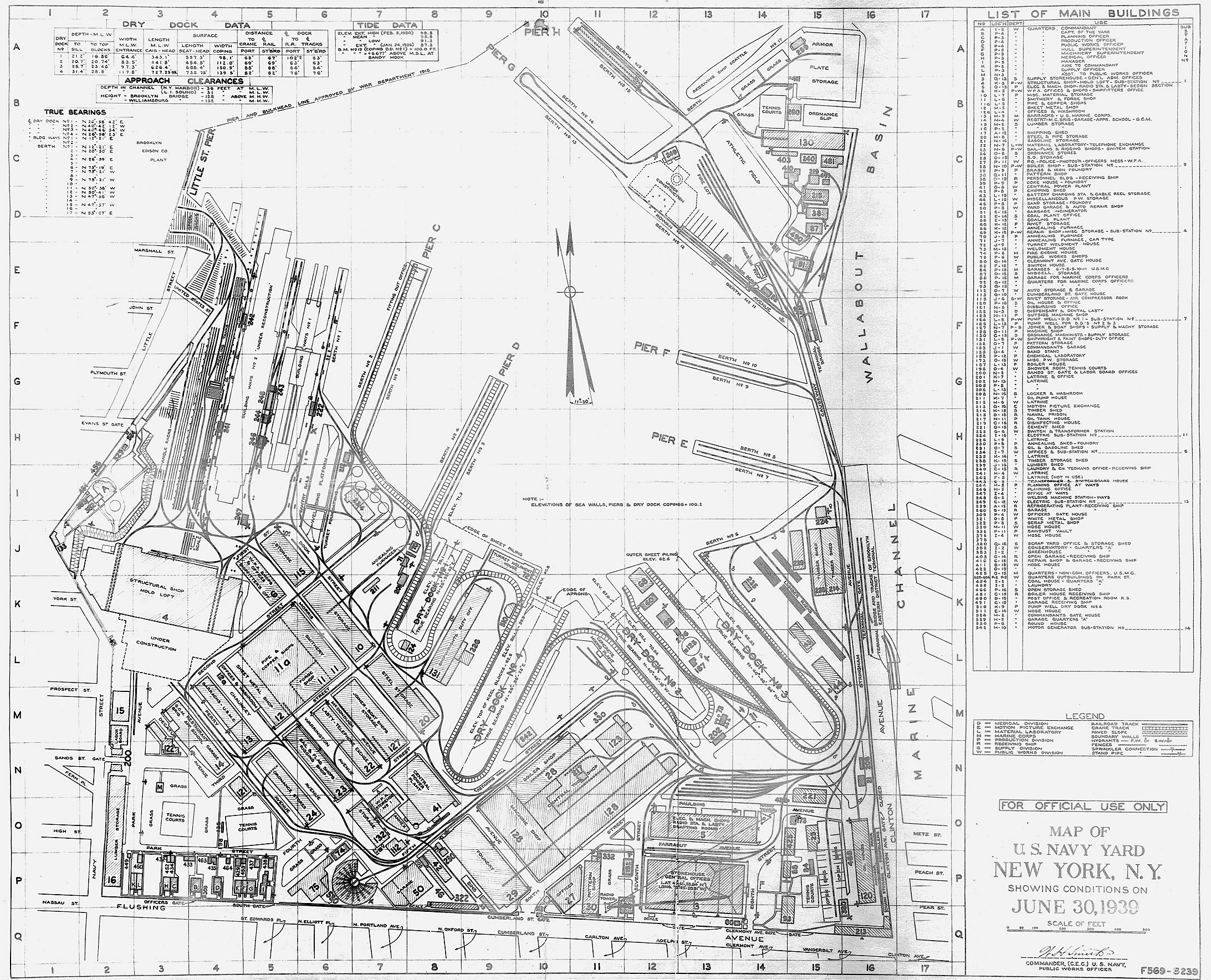

But in order to complete this ambitious plan, the yard needed more space. In early 1940, the navy made preparations to take over the neighboring Wallabout Market, which was at the time one of the world’s largest wholesale food markets. More than 700 farmers, grocers and merchants were forced out of the market to make way for the construction, though many relocated to a new market in Canarsie.[3] This purchase didn’t just involve acquiring more land (and demolishing the Alfred T. White-designed market buildings), but the complete reconfiguration of the shoreline. The Marine Channel, which received barges and rail cars of produce for the market, was filled in to make way for the two new dry docks. Cob Dock, a tidal flat in the East River that had grown with landfill and ballast dumped by passing ships into the yard’s ordinance dock (and many other functions, as you can see in the top right of the first map below), was dredged and reconfigured into three new piers (G, J, and K).

But most impressive about this expansion was the speed with which it was completed. Older construction methods required the use of huge caissons to pump out all the water before digging and pile driving could begin. Dry dock 1, the oldest in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, completed in 1851, took 10 years to build and suffered massive cost overruns. Dry dock 4, the largest and most modern in the yard before World War II, was dubbed the “hoodoo dock” by its builders because the treacherous construction on the yard’s soft, sandy soil (which caused the massive stone and concrete basin the be extremely unstable and continually sink) claimed the lives of 20 workers. Originally projected to take three-and-a-half years to build, the project had lasted twice as long when it finally hosted its first vessel in 1912. Even 20 years later, it took the navy anywhere from three to eight years to build a new dry dock, but a new method of concrete pouring would change all of that. [4]

The Brooklyn Navy Yard’s new docks, which each measured 1,092 feet long and 150 feet wide (large enough to fit the Chrysler Building laid on its side), were built with the new “tremie” method. This innovation didn’t require the site to be pumped out and excavated before the concrete was poured. Instead, the area was dredged to the desired depth, and more than 12,000 piles were driven in the water to support the dock structure – for dry docks 5 and 6, these supports were driven down 70 feet into the riverbed to reach bedrock. Next, gravel was laid and graded underwater to form a bed for the dock, and a special mix of concrete was poured into submerged forms through a so-called tremie pipe. This construction was done in segments; once one segment was done, a coffer dam was inserted and the water pumped out so it could be completed. This allowed for the dry dock to begin servicing ships before it was fully finished – a feature that would become a necessity with the outbreak of war. The demands for material for this job were enormous – each day an average of 16 barges would bring in cement and concrete ingredients that were mixed on site. By late 1942 the two new dry docks were finished (as was the new Bayonne facility), and dry dock 4 had been lengthened by 32 feet, bringing its total length to 727 feet, large enough to accommodate older battleships and large cruisers of the time. (Still confused? Popular Science offered a visual explanation in their May 1943 issue).

But the dry docks weren’t the only things going up (or down) at the yard, as dozens of buildings were built during this period. Most passersby the Brooklyn Navy Yard today don’t get to see the dry docks (though dry docks 1, 5, and 6 are still in use by GMD Shipyard Corp. for commercial ship repair), one structure you can’t miss is Building 77, the gargantuan 16-story concrete block that has no windows on its first 11 floors. Though its history is not as well known, the speed and sophistication of its construction is just as impressive as that of the dry docks. This huge project was meant to be the principal storehouse for the yard, offering 950,000 square feet of floor space (for another comparison, the 77-story Chrysler building has about 1.2 million square feet of space).

Its size would pose an interesting challenge, as with the dry docks, it risked sinking into the area’s soft soil; to support the building’s massive weight, pilings had to be driven down 150 feet before they reached bedrock. The entire building took only five months to build, and the main structure was built in just 48 work days, averaging one story every three days.[5] That count even includes three days that were lost in July 1941 to a strike by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. The city-wide 8,000-man strike, sparked by Consolidated Edison’s refusal to hire union workers, continued for two weeks, but the union agreed after three days to suspend the strike for defense-related projects.[6] As the New York Sun reported about the new navy yard building, “During each of these three-day periods 200 tons of re-enforced steel were set, 2,100 cubic yards of concrete were poured, 61,000 square feet of floor finish was applied and all incidental mechanical and installation work was performed. At the same time the exterior concrete wall inclosing one story of the building was put into place every two days” (September 2, 1941).[7]

While the official functions of Building 77 over the years have been rather mundane (a 1943 map notes: “Administration Bldg and General Storehouse”), its imposing and secretive appearance have inspired many oft-repeated legends over the years, from bomb storage to the Manhattan Project, though neither are true. The most interesting stories about the building we have heard come from the yard’s photographer Wesley Fagan (who passed away earlier this year at age 101), who used to develop his photos in the building, and a navy veteran who came on one of our tours this spring and recalled working on electronic warfare and radio interference experiments there (70 years later, he still didn’t feel comfortable going into detail about the then-classified project). Today the building is still used for photography – B&H Photo processes online developing orders there – and it is slated to undergo a major renovation and upgrade by the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation (which manages the yard property for the city) to bring the whole building online for leasing.

Pouring concrete may not be the most glamorous endeavor, but the millions of cubic feet of it that went into the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and into shipyards across the country, were just as important as the steel and munitions that went into America’s war machine. Thanks to Morreel’s plan, from 1939 to 1945 the federal government would invest $590 million in the upgrade of its navy yards, and in just a two year period – 1942 and 1943 – the navy would complete construction of 26 new dry docks, 14 on the Atlantic and 12 on the Pacific.[8] This engineering might and keen foresight would turn the tide of war, bringing more firepower to the fronts – and keeping it there in working order – than the enemy could ever hope to match.