New York City was far removed from the battlefields, occupied territories, and blockaded countries locked in the struggle of the First World War. While many of those places experienced food rationing, shortages, even deadly famines, the US was largely spared these deprivations. Nevertheless, the war was extremely disruptive to the food system of the nation and New York City, leading to the creation of new modes of food distribution to respond to this national crisis.

The outbreak of the war in July 1914 caused a shock to markets across the world, and the US was not immune. Ordinary New Yorkers saw huge spikes in the price of food almost immediately, and accusations of speculation and gouging were hurled at everyone from international bankers to meatpackers to street peddlers. Price increases were so sharp, and so widespread – within one month, the price of flour was up by one-third, while that of sugar nearly doubled – that many believed it was the result of, as the city commissioner of weights and measures put it, “a criminal conspiracy.”

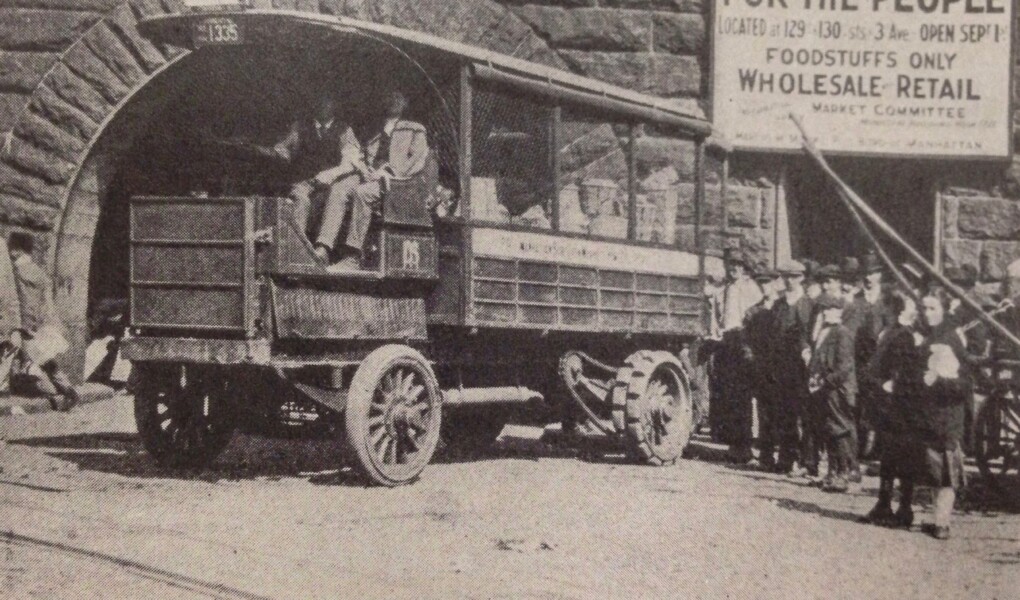

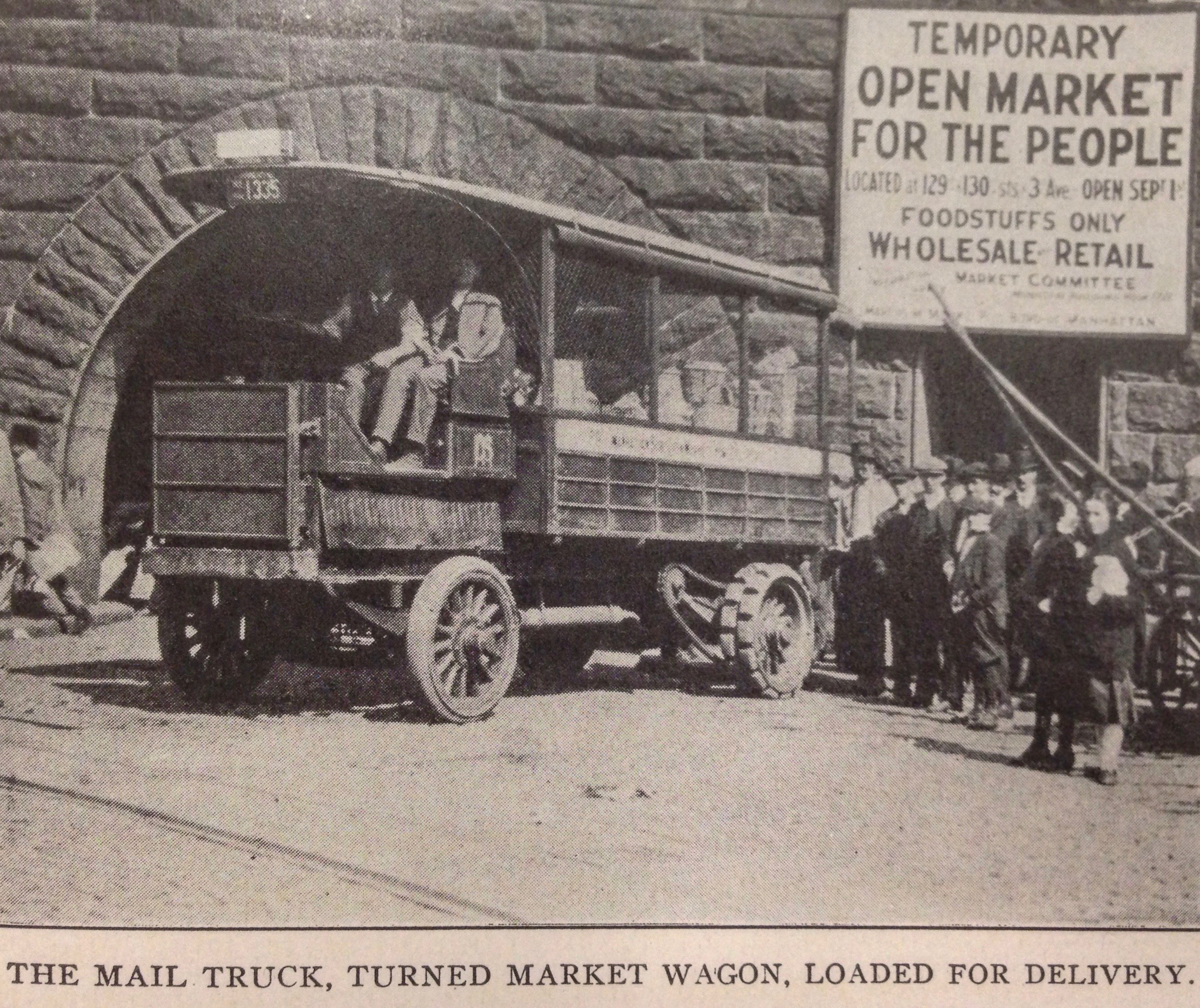

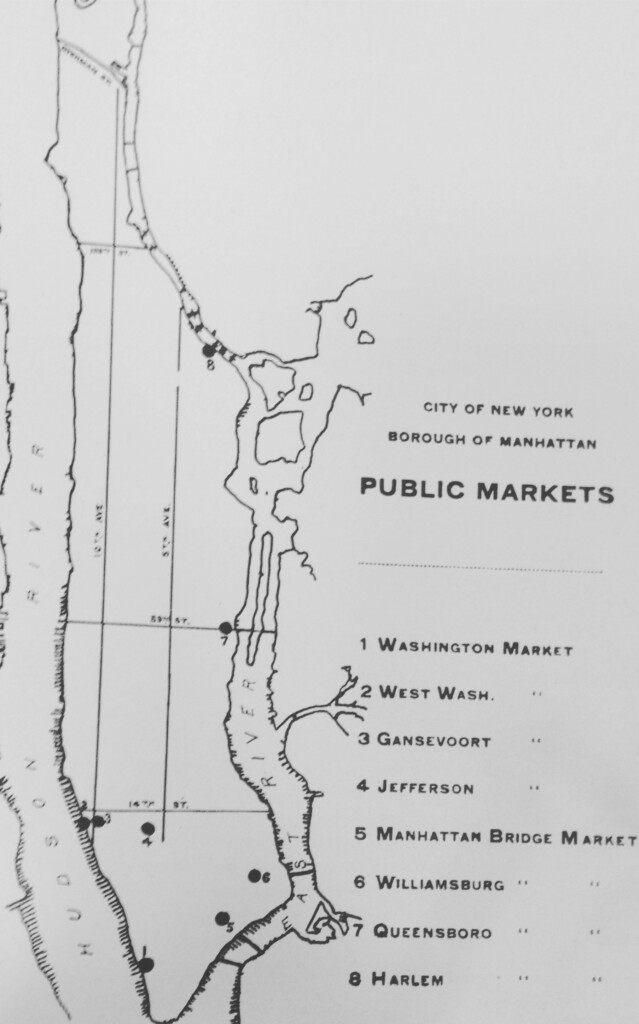

Within two weeks, Mayor John Mitchel convened a Food Commission to investigate the issue, and within a month the commission had set up a network of four retail markets where famers and wholesalers could get stalls rent free to sell food direct to consumers. The markets were found underneath the Manhattan, Queensboro, and Third Avenue (then known as the Harlem) Bridges, and at the Fort Lee Ferry on 130th Street. The markets were a smashing success, not just in serving low-income patrons, but, as one reader wrote to the New York Times, “They seem to fill the crying east side and the stricken sufferers of Billionaire’s Row alike. At a distance you can’t see the Queensboro Market for the limousines.”

Throughout the fall and winter of 1914, the initial price shocks began to subside, but these new public markets remained packed with hungry customers drawn to their selection and lower prices. City officials had long wanted public investment in the city’s food distribution system to increase efficiency and reduce costs for ordinary citizens. In November 1914, the city began lobbying New York State to authorize the establishment of a city Department of Markets. It took much political wrangling, but the department was finally created in June 1917.

The war also forced the city to contend with another long-simmering issue: what to do about the thousands of pushcart peddlers. For years, the city had been proposing to abolish pushcart peddling on city streets. In 1906, a commission set up to address this very issue had considered restricting them to designated area, but rejected the idea, concluding, “We can see no reason why … taxpayers should be called upon to bear such a burden.” With the food crisis abating, some of the “open markets” were closed, and the city saw an opportunity; as the farmers and wholesalers moved out from under the Manhattan Bridge, the city established its first official open-air pushcart market in the same spot, in July 1915, followed by another under the Williamsburg Bridge.

This would be the first step in establishing a citywide network of these markets that would grow over the next twenty years to more than 60 locations. While these markets provided affordable space for pushcarts, they also gave the city a pretext to crack down on “itinerant” peddlers, who operated on public streets; in 1917, an ordinance banned vending on sidewalks or within 500 feet of any of these open-air markets.

Despite these government interventions, food prices remained unsteady throughout this period, with big hikes in 1916, and a severe shock in February 1917, and uncertainty would only increase when the US officially entered the war in April. In this context, pushcarts were seen by some not as a menace, but as an asset – an army of mobile, efficient food distribution points with low overhead. The establishment of the Department of Markets empowered the city to address challenges of distribution, storage, and waste, but these usually required big, long-term infrastructure investments. Like in the summer of 1914, the city needed a quick fix to the food scarcity issue, and they turned to street vendors. In February 1918, the city’s Food Commission declared the “Restoration of the pushcarts is a war measure. … Great quantities of food that are now being wasted at the wharves can be quickly and cheaply put on sale in the tenement districts by pushcarts.”

Street vendors were not just enlisted into the war effort to sell food. Many also sold “Thrift Stamps,” which were essentially small war bonds. While the smallest denomination of Liberty Loan bond was $5, this was far too much money for many of the working poor; instead, they could buy these stamps for as little as 25 cents and combine them to get a full bond worth $5 at maturity. In May 1918, the peddlers of Orchard Street on the Lower East Side, more than 500 of them, launched a drive to sell the stamps. One of the peddlers, Simon Jeremovsky, originally from Kiev, said, “Today I am not a peddler for myself. I am a peddler for the Government – and if I could afford it, I would be a peddler for the Government every day until the war is at an end.” The following month, 3,000 peddlers paraded through the Lower East Side to sell the stamps, rallying at the Liberty Loan office on Delancey Street and Allen Street.

Another vendor did not sell these war stamps – he invested his own profits in them. In September 1919, Moses Siegel, a 78-year-old Orchard Street peddler, took his pushcart all the way down to the Federal Reserve Bank on Nassau Street, walked inside, and deposited 200 stamps, enough to purchase a war bond worth $1,000. He told the New York Times it was the first time he had ever been in a bank in his life.

The years 1914-1918 really were the genesis of New York City’s wholesale and retail public market system. For many years prior, the city had been contemplating opening public markets; they were seen as a vital necessity to improve the distribution, storage, and sale of the vast quantities of food needed for this city. So the war did not create these issues; it merely made them more pressing, forcing the city to act quickly, and take advantage of the resources at its disposal.