John Ericsson (1803–1889)

John Ericsson was perhaps more of an engineer than any man who ever lived. Of his 85 years on this earth, 75 of them were spent as an engineer, and he worked in almost every conceivable field of engineering a person could in the 19th century, spanning the apogee of the Industrial Revolution.

Born in Värmland in central Sweden in 1803, Ericsson came from a family of engineers. At 10, he designed a water-powered sawmill, and at 13 he became a trainee engineer working on the Göta Canal, a massive waterway connecting the North Sea and Baltic Sea. After time spent in the army and as a surveyor (his only formal training), it appears civil engineering did not suit him, so in 1826 he switched to mechanical engineering and moved to England to work on his ideas for engines. Within three years, he had devised a locomotive good enough to be entered into the famous Rainhill Trials, which were staged to select a design for the new Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Though Ericsson’s Novelty proved faster than Stephenson’s famed Rocket, it was plagued with reliability issues and lost the contest.

Ericsson then turned his attention to naval architecture, and during the 1830’s and 1840’s, he contributed greatly to the development of the naval screw, or propeller, proposing designs for the British Admiralty. Steamships had already been in service for decades at this point, but they were all of the paddle-wheel design. Not only was this large wheel mechanically inefficient, but for warships, it was a major weakness, as it was exposed above the waterline. One of Ericsson’s major innovations was to place the whole propulsion system below the waterline, making it far less vulnerable to enemy fire. But after again losing out to competitor designs, he decided in 1839 to move to New York, where he found a more receptive audience.

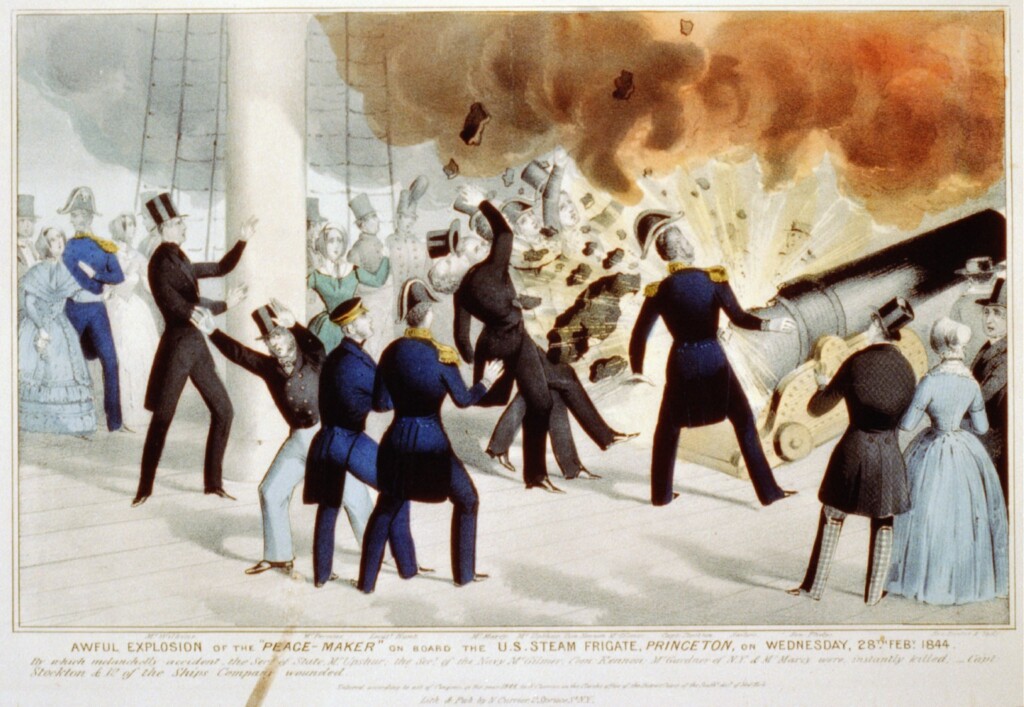

He eventually won a contract to build the US Navy’s first screw steamer, USS Princeton, which incorporated many other mechanical innovations. Though the Princeton was in many ways a technological success, Ericsson’s relationship with the Navy soured; perhaps this was because during a demonstration cruise in on February 28, 1844, one of the ship’s guns exploded, killing six people, including the Secretary of State, the Secretary of the Navy, the Navy’s chief constructor, a Belgian diplomat, President John Tyler’s enslaved valet, and the father of the president’s fiancée—and narrowly avoided killing the president himself.

But Ericsson is best known for his game-changing design, the USS Monitor, completed in 1862, which brought him into direct contact with the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Ericsson had proposed all-iron ship designs before the Civil War, but they were met with little enthusiasm. However, when word reached Washington that the Confederates were constructing an invulnerable iron-sided ram, building iron ships became an urgent project. Ericsson initially ignored the Navy’s pleas, but he was finally convinced to submit a proposal, and it was accepted personally by President Lincoln, who overruled skeptical Navy brass. His design was essentially a raft, drawing just eight feet of water, and rising less than two feet above the water, with a rotating armored turret mounted on top, carrying just two guns. Since the Navy worried about the unconventional design, Ericsson and his partners were given a contract that obligated them to refund all of the money for the ship if it did not perform up to specifications, which Ericsson agreed to, having full faith in his design.

So Ericsson set to work, contracting the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint, Brooklyn to build the hull, and the Novelty Iron Works, located right across the river in Manhattan, to build the turret. While he had promised to deliver the ship in just 100 days, it took 118 days from keel-laying to launching, and it arrived at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on February 19, 1862 for sea trials. Not everything went according to plan; the steam engine malfunctioned, forcing it to be towed to the Navy Yard, and an improper installation of the rudder controls rendered the ship un-steerable. Quick adjustments at the Yard had it ready for action, and it was commissioned into the Navy on February 25 and left for its date with destiny just nine days later.

March 9, 1862, was the day that every navy in the world suddenly became obsolete. The day before, the Confederate ram, built on the hull of the captured Union steam frigate USS Merrimack and rechristened CSS Virginia, roared out of Hampton Roads and began laying waste to the Union blockade. Cannon fire bounced harmlessly off its sides as it slammed its reinforced prow into its opponents and raked them with broadsides. As night fell, it appeared is if this singular vessel would break the whole of the Union fleet, and then mercilessly bombard northern cities. But then an odd vessel, barely visible above the waves, appeared in the harbor. The next morning the Virginia emerged to do battle, only to find that another ironclad opposed it. The two dueled for more that three hours, neither able to inflict significant damage despite scoring dozens of direct hits on one another. They eventually both retired from the battle; though a tactical draw, it was a strategic victory for the Union, who had neutralized the Confederacy’s most potent weapon. Ericsson’s bet had paid off.

The Monitor then became a template for a fleet of ships in the American and other navies. Though ill-suited for the open ocean (the Monitor sank on December 31, 1862 in rough seas off Cape Hatteras), these vessels proved effective in the coastal and inland waterways where the Civil War was mostly waged. Even double-turreted variants were built, led by the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built USS Miantonomoh. But most importantly, the success of the Monitor forced the Navy Yard, and shipyards across the world, to transition from wooden to iron shipbuilding. More blacksmith and machine shops sprung up across the Yard, and its first dedicated armor plating shop opened in 1865, which still stands today.

The Monitor was by no means the end of Ericsson’s career. He continued designing ships, including a class of monitors for the Swedish Navy, and working on new ideas for naval gunnery. In 1881, he constructed a concept vessel called Destroyer, which had a large cannon mounted below the waterline and was capable of firing explosive projectiles underwater. That year, the ship was brought to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for testing, which was not entirely successful. The Navy decided to pass on the design, choosing instead to invest in developing self-propelled torpedoes. Ericsson died in New York City on March 8, 1889—27 years to the day after his Monitor arrived in Hampton Roads to save the US Navy. Though he is not buried in New York—his remains were repatriated to Sweden the following year— a large statue of him holding the Monitor stands in Battery Park.