The Academy Awards are tomorrow night, and nominated is a film that has only hit American cinemas in wide release this weekend, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, up for Best Animated Feature. I had the opportunity to see the film during its limited release back in November, a three-day run that made it eligible for an Oscar this year, and I saw it again during its official premiere on Friday. While its love story is beautiful, its engineering story is fascinating, it’s the moral and historical drama that unfolds almost in the background that I found most compelling.

The film tells the story of Jiro Horikoshi, an aeronautical engineer born in 1903 who is best known for designing the Mitsubishi A6M fighter plane, better known as the “Zero.” Since the film’s release in Japan last summer, it has sparked great controversy, criticized by both the left – who believe it celebrates a maker of war machines – and by the right – who say it is overly pacifist and denigrates pre-war Japan. In my view, one of the film’s great strengths is its portrayal of Japan as a conflicted nation, in which most people had little more than a premonition of the disasters that lie ahead.

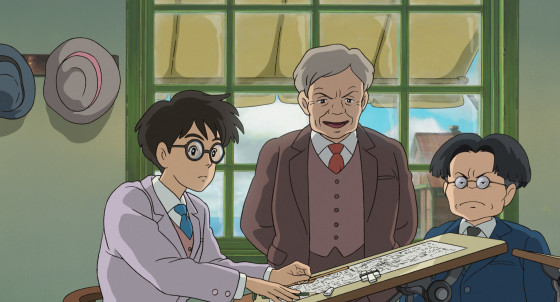

Throughout the film, Jiro is a dreamer, and his dreams are aircraft. He is frequently visited in his dreams by Gianni Caproni, an Italian aircraft designer of an earlier generation who inspired the young Jiro with his audacious, fantastical designs, like the nine-winged Ca. 60, a 100-seat passenger liner that broke apart on its maiden flight, depicted in the film. In these dreams, the two engineers discuss the internal conflict of airplane designers – that they strive for beauty and precision and the miracle of flight, yet they know that their creations will be used for war. Jiro’s dreams are interrupted by specters of death, the sky filled with bombers, and his own creations falling from the sky in flames.

A theme that is repeated throughout the film, often in conversations between Jiro and his classmate and fellow Mitsubishi designer Honjo, is the poverty and backwardness of Japan. One striking example is the fact that at the Mitsubishi factory, the state-of-the-art airplanes are transported from the factory to the airfield by oxen. Honjo laments that a poor country like Japan would waste so many resources on warplanes, that a single part on a single aircraft could feed a family for a month. But, he admits, “Poor countries want airplanes.” Meanwhile, both men continue their work.

Outside of his dreams, Jiro rarely expresses his own misgivings about his work, and at times even seems willfully oblivious. When he suggests that an engineering problem could be fixed by removing the aircraft’s guns, he is met by a chorus of laughter from his fellow engineers, but you get the feeling that Jiro was not joking.

The film frequently foreshadows Japan’s inevitable calamity in a number of ways. One of the early scenes of the film shows Jiro on his way to university in Tokyo, when the 1923 Kanto earthquake struck. One of the deadliest in history, the quake sparked fires around the capital, burning it almost entirely to the ground, killing roughly 140,000 and leaving nearly two million homeless. Looking back, many Japanese saw this as a harbinger of what would come to their country 20 years later – and the vision of Tokyo again aflame returns in Jiro’s dreams.

Except instead of coming from deep in the earth, it would come from high in the sky.

In The Wind Rises, these calamities come only in dreams, but we can hear the stories of people who actually lived through them. Japan at War: An Oral History is a remarkable collection of stories collected in the 1980’s and 90’s of Japanese who lived through war. Haruko Taya Cook and Theodore F. Cook’s collection captures the perspective of ordinary civilians, soldiers, sailors, journalists, and politicians, some of whom lived out the war at home, while others were scattered to fronts in China, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific. Together, these stories create a diverse narrative of the many different ways that people explain the past and their part in it.

Often, the author’s note, the subjects point to Japan’s relative poverty as the reason for their defeat – defeat was caused by “Allied production process, to blame materiel rather than people.”[17] But their recollections also seemed as if they were in a dream: “Japanese memories of the Pacific War can have a structureless quality in which the individual wanders through endless dreamlike scenes of degradation, horror, and death, a shapeless nightmare of plotless slaughter.”[14]

On of the realities of the war, which often goes unappreciated by American and Japanese audiences, is that it was almost over before the first Zeros dropped their bombs on Pearl Harbor. It is important to remember the deadly efficiency of the American war machine, one which took only a short time to get up to full power. As American men enlisted and industry ramped up production in December 1941, Japan had already slogged through four-and-a-half years of war in China. Between 1941 and 1944, America built more than 260,000 aircraft; Japan could not even muster 60,000, and even those, along with their experienced pilots, were being shot down far faster than they could be built.

Sakai Saburo, an ace of the Zero interviewed in the book, referred to the loss of Japan’s best pilots – and their knowledge to train future pilots – as “leaving us like a comb with missing teeth.”[138] And by the time air bases for heavy bombers were secured within range of the home islands, American airplanes filled the skies of Japan, and there was little or nothing they could do about it.

The Zero was a beautiful, maneuverable fighter – just as Jiro had dreamed of – but against its American counterparts, it was under-powered, lightly armored, and lacking heavy weaponry. The Japanese could design the most advanced fighter in the world, but they lacked the raw materials to build it in any numbers, and by the end of the war, the fuel to get it up in the air. American planes like the Grumman Hellcat were built for speed, firepower, and survivability; an agile Zero could get a jump on one, but it couldn’t beat a squadron flown by experienced Navy pilots.

Jiro’s dream was instead reduced to suicide missions, flown by green pilots who could not handle the plane in dogfights with the Americans, ramming into ships in a last-ditch effort to save the flagging empire. Hata Shoryu, a reporter who covered the war, noted, “Victory and defeat for air units were determined by altitude, speed, and firepower. No matter how much you asserted bushido [the Japanese concept of the warrior spirit] there, if you didn’t have the speed you couldn’t escape or overtake your opponent. Japan lost because it didn’t have any of them.”[210]

While most Americans know of, and to a certain extent appreciate, the impact of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the conventional bombing campaign of Japanese cities is less well known. We celebrate the daring Doolittle Raid, when 16 bombers flew over Tokyo in April 1942 and crash landed in China, but the missions against the home islands in 1945 were far more devastating, and mostly forgotten. In all, 67 Japanese cities were wholly or partially destroyed, and at least 300,000 civilians were killed – and that’s excluding the atomic bombings.

The mission over Tokyo on March 9-10 was the most destructive, when 334 B-29’s firebombed the city, killing some 100,000. Resistance was minimal – Zeros’ bullets bounced off the armored bombers, and many of the pilots resorted to mid-air kamikaze ramming attacks – and 320 of the bombers returned to base in the Mariana Islands. Most of the Japanese fighters sat in their hangers, preserved for use in the “final battle” against the American invasion fleet that never came, while Tokyo burned.

Throughout Japan at War, the subjects note the moment they realized the war was lost, and for most it did not come when the skies filled with American bombers, or when Marines island-hopped closer to the home islands, or when the emperor announced the surrender. Instead, the realization came at seemingly more mundane moments. For Nogi Harumichi, a naval administrator in the occupied Dutch East Indies, it was when he saw his men confused by a western-style toilet. For Ogawa Tomatsu, a prisoner of war in the US, it was when he saw an American construction crew build an airstrip in a single day. For Fujii Shizue, who’s husband was a POW, it was when she saw Scotch tape, an unheard of technology in Japan, affixed to his letters home.

The Wind Rises concludes before any of this takes place, and we are left only with Jiro’s dreams of the future to ponder his place in a country and a world transformed by war. To understand his place, we must gain a deeper understanding of the war for the Japanese, which was as an unbridled tragedy, one which many still recall as a sort of dream. This is not to excuse any of the horrors visited upon other peoples by Japanese forces during the war, but to acknowledge the sheer destructiveness of the force unleashed in reply, and the effects of that force that resonate to today. A gifted engineer, a loving husband, a dedicated friend, Jiro can be a stand-in for the millions of ordinary people who lived through Japan’s war, some complicit in the nation’s crimes, some not, and most somewhere in between – just like the rest of us.