Earlier this year, Cindy and I had the privilege of visiting one of the largest and most decorated ships ever built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the battleship USS Iowa. Launched from the Yard in 1942, for more than a year she has resided in Los Angeles as a fantastic museum ship. Thanks to the wonderful hospitality of the Iowa‘s staff, we got an up-close view of this historic piece of Brooklyn handiwork.

When we arrived at the Iowa last spring, we were greeted by Dave Way, the museum’s curator. Over the course of two days, Dave spent several hours with us showing off the ship’s exhibits and archives, and even taking us around some of the areas of the ship that most visitors don’t get to see. Transforming the Iowa into a museum was a monumental task, and Dave has been part of this project for several years. Along with a core group of volunteers, he spent nine months living ins spartan conditions on board the ship up in the Bay Area, working tens of thousands to fix and clean the mothballed vessel. Once the work was done, the Iowa was then towed down to her berth in San Pedro, where she finally opened to the public on July 4, 2012.

What struck me most about visiting the ship in person was the sheer scale. On our Brooklyn Navy Yard tours, we frequently reference facts and figures – 45,000 tons displacement, 887 feet in length, nine 16-inch guns capable of firing 2,700-lb projectiles 26 miles – but they’re just numbers. When you’re standing on the deck of this behemoth (or staring down the barrel of those 16-inchers) you can much better appreciate the meaning of other numbers, like the 4.1 million man-days it took to build her, the 800 miles of welding holding her together, or the half-million pounds of paint that went into her first paint job.

What is also striking is how the ship’s longevity, having served through so many different eras and conflicts. The Iowa was the first of a new breed of ultra-modern battleships that would be pride of the American fleet in World War II, but she, along with the Iowa-class vessels Missouri, Wisconsin and New Jersey, has been in a bit of a revolving door for 70 years, moving repeatedly between the active and mothball fleets. This is in part due to the fact that these ships are the last battleships the US ever built, and in part because they are simultaneously obsolete and uniquely capable, depending on whom you ask in naval warfare circles.

While the US Navy has shifted to more flexible vessels with more advanced weaponry, the Iowa and New Jersey technically remain in the reserve fleet. Even today, they still carry the largest guns in the Navy, and they have stood up remarkably well. While ship-mounted cruise missiles can do damage from hundreds of miles away, many military planners believe the Iowas can still perform certain roles more effectively (and cheaply) than more modern counterparts. Caught in this decades-long debate, these ships have each been commissioned and then decommissioned on three separate occasions – during World War II, the Korean War, and in the 1980’s (the New Jersey was also recommissioned during the Vietnam War).

The most controversial return of these battleships was during the Reagan administration, when they were reactivated in the Cold War drive for the “600-ship Navy.” During this period, the Iowa nearly returned to the place she was born – Brooklyn. As the Navy was looking for a new homeport for the ship, both the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the Brooklyn Army Terminal were considered, though the never-completed Staten Island Homeport in Stapleton was ultimately selected. The ship’s return to duty would be short-lived, however. In April 1989, during a fleet exercise off Puerto Rico, one of Iowa‘s turrets exploded, killing 47 sailors. Controversy swirled around this accident (which naval investigations initially concluded was the result of sabotage by a crewmember, though this is heavily disputed), and many critics pointed to it as proof of the danger of the Iowa refit program. But the collapse of the USSR and the subsequent drop in military spending probably had more to do with the re-mothballing of the ships than the accident, as all four would be decommissioned by 1992.

And today, the battleship debate rages on (even arising tangentially in one of last year’s presidential debates), affecting naval strategy, shipyards and, strangely, museums. Though the Iowa is now a museum ship, it still is a member of the Navy Reserve Fleet, and the museum is required by law to keep it up to a certain standard of working condition, until at least 2020. That means with some effort, she can be made ready to sail, and all of its major systems, including its guns, still work. She even has a working kitchen, a rarity on board historic ships (perhaps our friend Sarah Lohman could do a cooking demonstration of World War II-era battleship galley fare). But specific infrastructure was built to construct and service these ships, and the ships themselves may outlive it. In a past era, a central feature of the Brooklyn Navy Yard was its massive 350-ton hammerhead crane. Built in 1941, it was designed to lift and install the 16-inch gun turrets of the Iowas. Our crane was scrapped in 1965, but a nearly identical one, designed for the same purpose, still stands at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia. It hasn’t been used since 2001, and the Navy would like to tear it down; as it is one of the last cranes of its kind, scrapping it would likely spell of the end of the line for the Iowas as combat vessels.

This debate aside, you can still find reminders of the many different periods of service throughout the ship. The museum has fully restored the special cabin created for President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he sailed to North Africa en route to the Tehran Conference in 1943 – several of the bulkhead doors had to be cut out to allow him to move between rooms in his wheelchair. Stepping into the lower decks, you can find the fire control systems, used to aim the 5- and 16-inch guns. Filling two entire rooms, these World War II-era mechanical-analog computers performed so well that during the 1980’s refit, there was no need to replace them with modern digital systems. But most of the ship’s systems were modernized – moving up to the ship’s superstructure, several large white objects look out of place amidst the sea of grey. Though they look like hot water heaters, these are actually the Phalanx Close-In Weapon System, a radar-controlled machine gun capable of firing 75 20mm rounds per second, a wall of lead that can down a missile or aircraft headed towards the ship. This is probably one of the biggest changes to the Iowa over its history, as these four cannons, along with some other missile systems, replaced the 70+ anti-aircraft batteries originally mounted on the ship, and the hundreds of sailors it took to man them.

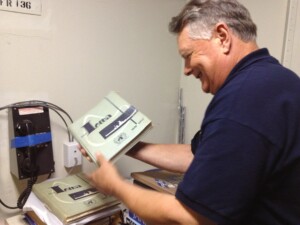

On our visit, we also got a chance to see a bit behind the scenes in the museum’s archive. Since opening, the battleship has been inundated with donations of artifacts and documents from some of the tens of thousands of men and women who served aboard the ship. Additionally, the ship was packed with manuals and other documents relating to its most recent service period in the 1980’s, as well as to its upkeep and care during mothballing. This trove is a blessing, but it can also be a curse, as incredible amounts of manpower and resources are required to sort, catalogue, and preserve this material. Luckily, the Iowa has a great group of staff and volunteers to help sift through it all.

The Iowa‘s opening marked two important milestones for historic ships. It became the last of the Iowa-class ships – all of which are still afloat – to open to the public as a museum; it was also the last of the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s three World War II-era battleships to become a museum. The Brooklyn-made Missouri has been a museum in Pearl Harbor since 1995, standing watch over the sunken Arizona, which was also launched from Brooklyn in 1915. You can visit the New Jersey in Camden, NJ, or the Wisconsin in Norfolk, Virginia. And the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s North Carolina, a precursor to the Iowa, has also been preserved as a museum in Wilmington, NC. We are lucky that all these historic ships have escaped the scrapyard and carry on important educational missions. And this is thanks to groups of dedicated volunteers and civic organizations that worked to preserve these vessels and continue to interpret their history for future generations.

Special thanks to Dave Way and all the folks at the Battleship Iowa Museum, and also thanks to Shawn Welch of the US Army Corps of Engineers and Battery Gunnison for providing excellent insight into the Iowa refit program.