Today marks the 57th anniversary of perhaps the darkest day in the history of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. To commemorate the fire on board the USS Constellation, we are going to look back at some of the most notable and deadliest accidents in the history of the Yard.

Shipbuilding is a dangerous business (even today), and fatal accidents were frequent throughout industry in the nineteenth century. The scale, pace, and nature of the work in the Navy Yard made it particularly risky, as workers and sailors fell victim to hazards like falling from great heights, being struck by heavy loads, violent machinery, drowning, fires, and exploding munitions and equipment. Workplace safety began to improve around the time of World War I, and more concerted campaigns began during World War II, when safety was urged as an imperative of national security.

As technology and safety have changed, so have the hazards facing workers. The is by no means a comprehensive list, but it speaks to these shifting hazards, and some of these accidents had a lasting impact. So today we are going to look back at some of the worst accidents in the Yard’s history across many different eras.

June 4, 1829: Receiving ship explosion

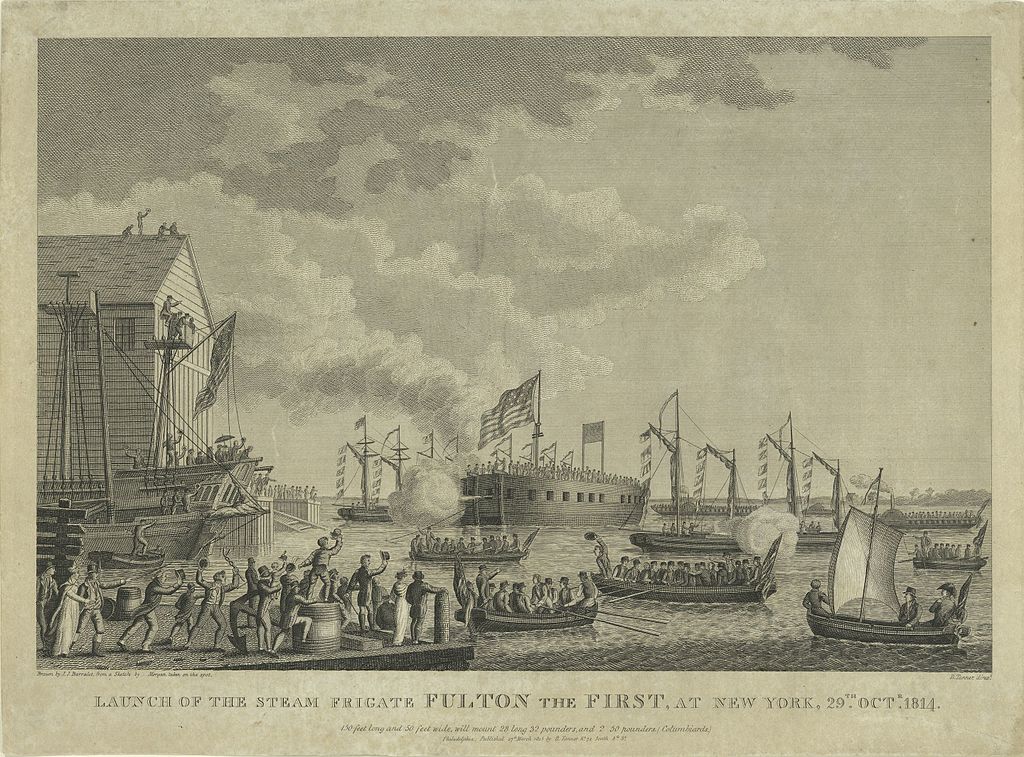

The floating battery Demologos was one of the most star-crossed ships of the early US Navy. Technically the country’s first steam-powered warship, it was designed to act as a moveable and impervious fort to defend New York during the War of 1812, not a true seagoing vessel.

Designed by Robert Fulton, both its inventor and the war it was designed to fight would meet their ends before the ship was ready for service. Built by Manhattan shipbuilders Adam and Noah Brown, the ship was never officially commissioned, and spent only two days “at sea” – once on its sea trials on June 14, 1815, and again two years later when the ship was used to take President James Monroe on a tour of New York Harbor. By then is had been renamed Fulton in the designer’s honor.[1]

After years of sitting abandoned in the Navy Yard, in 1821 all of its machinery and weaponry was removed, and it was converted into a floating barracks. For eight years, it served as the main housing for officers and enlisted men at the Yard; in 1829, 143 people lived aboard, including the families of officers, many young wards of the Navy, and sick and injured sailors.[2]

At around 2:30pm on June 4, a loud explosion was heard. Commandant of the Yard Isaac Chauncey described the scene in a letter to the Secretary of the Navy:[3]

I had been on board the ‘Fulton’ all the morning, inspecting the ship and men, particularly the sick and invalids, which had increased considerably from other ships. … I had left the ship but a few moments before the explosion took place, and was in my office at the time. The report did not appear to me louder than a thirty-two pounder, although the destruction of the ship was complete and entire, owing to her very decayed state, for there were not on board, at the time, more than two and a-half barrels of damaged powder, which was kept in the magazine for the purpose of firing the morning and evening gun.

The cause of the explosion was determined to be carelessness on the part of one of the gunners, who had carried his candle with him into the magazine, rather than setting it down outside, as was regulation. The Long-Island Star described the results of that carelessness in gruesome detail:[4]

The scene throughout was one of the most distressing and awful that can be imagined. The bodies of the dead were horribly lacerated and in every variety of mutilation – bowels protruding, limbs wrenched off, brains scattered – the recollection is too sickening to be recited.

There is some dispute as to the total casualties of this accident. The Navy puts the official tally at 25, but accounts of the time should add several more names to the list. As reported by the Star, the coroner identified remains of at least 26 sailors, one officer, three women, and one infant, putting the total at 31.

1905–1912: Construction of Dry Dock No. 4

The tragedy at Dry Dock No. 4 was not one accident, but a series of calamities that unfolded over several years due to challenging geology, bad engineering, unscrupulous contractors, and, if you believe the newspapers of the time, a curse.

Construction on the dry dock, designed to fit new dreadnought-style battleships then under development, began in 1905. The site was less than ideal, as is much of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, for a construction project of this scale. Situated on a tidal marsh, the soil is very soft and sandy, while the water table is very high, and the site was crisscrossed with underground waterways. The first contractor quit the job after just 18 months of work, complaining of the low value of the contract for a huge expense.

In defense of the first contractor, George Spearin, the casualties seem to have been limited on his watch. The first death came before the construction even officially began, when laborer Lamuel Challinor fell down a shaft and died on December 8, 1904.[5] It was not until 1909, under the second contractor, the Williams Engineering Co., that fatal accidents started to occur with regularity. It was also during this time that the site gained its nickname – the “Hoodoo Dock” – suggesting that the site was somehow cursed.

Italian laborer Rocco Namo was killed on March 6, 1909, when he fell down a dredging chute, entombing him in mud.[6] Almost one year later, and under a new contractor, Cabot, Holbrook & Rollins, another Italian immigrant, Barano Michele, was killed when he fell 48 feet into a construction caisson.[7] That same year, Anthony Short, Anthony Wilson, and Walter Hitchcock were killed in separate falls into the every-growing pit of the dry dock.[8]

While most of these casualties were to contractors, there were also permanent employees of the Navy Yard who lost their lives. After Williams walked off the job, the Navy considered completing the project itself, but decided instead that a contractor should do it, as they could use cheaper immigrant (mostly Italian) labor.[9] On June 9, 1911, riveter Michael Brown was taking a shortcut through the site when a small wooden building collapsed on top of him, likely weakened by the shifting soil and construction vibration.[10] The last recorded fatality appears to be Thomas Walsh, who died after being hit by a falling pole on October 23, 1911.[11]

We could only find eight deaths recorded as a result of Dry Dock 4’s construction, though some accounts put that number as high as 20, and the injuries numbered in the thousands. After seven years of construction, the dock was finally completed on May 9, 1912, when the first vessel, the battleship USS Utah, docked there.

January 15, 1916: Submarine E-2 explosion

Going down in submarines has always been a dangerous business (though today it is one of the safest professions in the Navy), and accidents were frequent in the early days.

When commissioned in 1912, USS Sturgeon, later known as E-2, then as SS-25, was cutting-edge technology, equipped with the first submarine diesel engine in the US Navy. But as with many new technologies, it faced challenges. The engines created too much vibration, damaging the delicate lead-acid battery system. These batteries were a huge problem; made of lead plates suspended in sulfuric acid, sharp maneuvers could spill the solution, damage the batteries, and corrode the hull. And if any seawater got into the system – a common occurrence – they would produce deadly chlorine gas.

In June 1915, E-2 arrived at the Brooklyn Navy Yard to undergo a complete refit, replacing both the engines and the batteries. The new battery system was hailed as a technological marvel, designed by Thomas Edison. The batteries allowed the sub to travel much farther submerged – up to 150 miles – than previous batteries, and unlike lead-acid, these nickel-iron batteries were more durable and did not produce chlorine gas.[12]

The system did not prove to be perfectly safe, however, as the battery’s chemical reaction did produce hydrogen gas when charging; not toxic, but odorless, and highly combustible.

On January 15, 1916, while the sub was sitting in Dry Dock No. 2 undergoing charging tests on the new batteries, an explosion ripped through the battery compartment. Initial reports claimed that all 20 people on board – including civilian workers – were killed. Most survived, though four crew were killed in the explosion, while a fifth died days later from burns. Their names were:[13]

- Guy Hamilton Clark, Jr., machinist’s mate

- Roy B. Seaber, electrician, third-class

- Joseph Logan, Navy Yard plumber

- James H. Peck, Navy Yard plumber

- John P. Schultz, Navy Yard workman

A court of inquiry ruled that the accident was not the fault of the crew or the captain, but likely of the Edison Storage Battery Company, which had done insufficient testing and had not provided inadequate instruction in the venting of the battery system. The sub’s captain, Lt. Charles Cooke, had requested that hydrogen gas sensors and voltage meters be installed, but the Navy refused. While Edison’s representatives sought to blame some other source – diesel fuel, compressed air, or an errant spark or cigarette – the hydrogen gas was undoubtedly the culprit, and the crew, some of whom had suffered permanent crippling injuries, all testified that they had followed strict safety protocols.[14]

Following the inquest, the refit was completed, and E-2 went back into service, mostly as a training and testing vessel, though it also sailed a few patrols off the Atlantic Coast in the waning months of World War I. Ultimately the Navy decided to abandon Edison’s technology, and modified versions of lead-acid cells were developed, and that remains the foundational technology of most modern submarine batteries.

Incidentally, the chief of submarines at the Navy Yard, and a participant in this inquiry, was a 30-year-old lieutenant named Chester W. Nimitz. Nimitz climbed to he rank of Fleet Admiral, commanding Pacific naval forces in World War II, but his career (and his life) was nearly cut short by an accident, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Later in 1916, while explaining the intricacies of a diesel engine, his left hand became caught in the machinery, stopped only by a ring (some accounts say it was his wedding ring, but most agree it was his Naval Academy ring), which allowed him to pull his hand out, minus his ring finger.[15]

December 19, 1960: USS Constellation fire

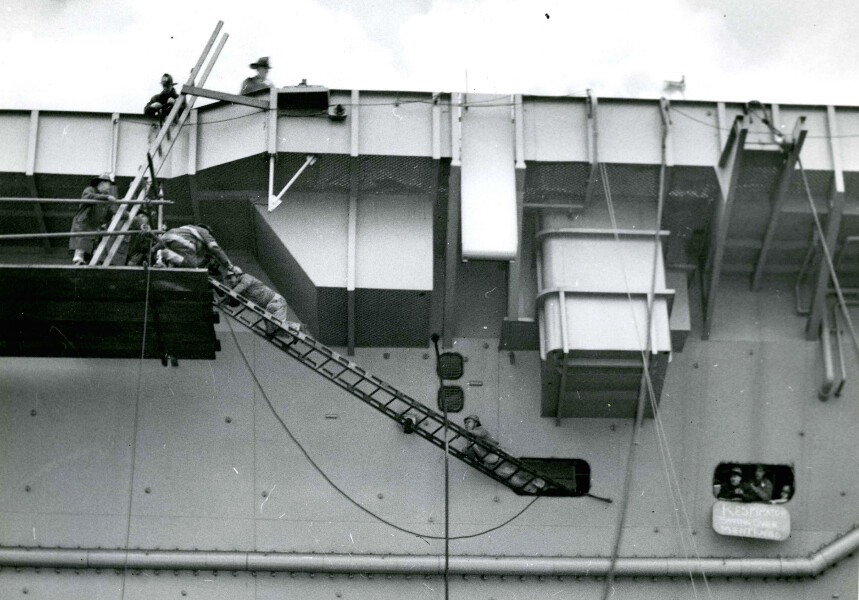

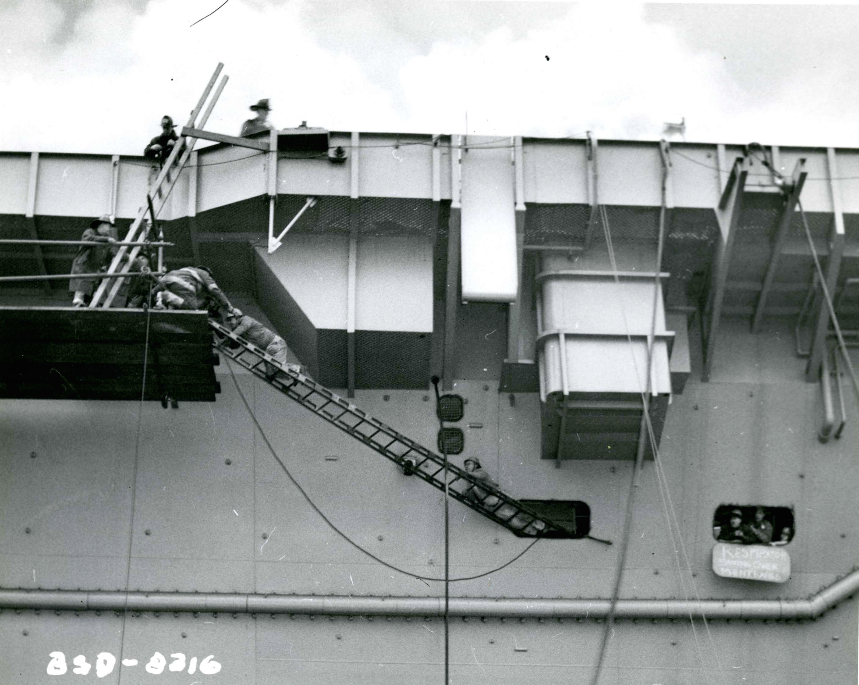

The deadliest accident in the Yard’s history occurred on a cold Monday morning in December. For three years, the Yard had been consumed by this massive project, constructing the world’s largest aircraft carrier, a 60,000-ton behemoth. The ship had slipped into the East River ten weeks earlier, and finishing work was being done at Pier K on the Yard’s far eastern edge.

Unlike the these other events of the distant past, we have had the privilege of meeting people who lived through the ordeal aboard the Constellation, and we would like to share some of their recollections.

In 2014, we hosted the 50th reunion of the Brooklyn Navy Yard Co-op, a program of Pratt Institute that gave college students on-the-job training at the Yard. In December 1960, this group of college sophomores was learning the ropes of engineering, drafting, management, and, for Mike DeLucia, safety. He shared this in an oral history he recorded during the reunion:[16]

So McCartney [his supervisor] and I went out to the ship, went out to the hangar deck and set up the PA system. We had it all set up and were testing the mics and everything. We were basically waiting for the show to start. And we were happy everything was done. And all of a sudden, McCartney noticed an oil slick. I didn’t know what it was, it was like a big huge black puddle of something, flowing on the hangar deck. And here, I immediately recognized that it was a fire hazard, you know.

So he immediately told me to go up above on what they call the galley deck, which was the deck right above the hangar deck and below the flight deck, because he knew there was some welders working up there and a welding torch would ignite this thing. So he said, tell them to cut all welding and stop welding. And then alarms went off. I remember alarms going off and people running for fire extinguishers. They formed sort of a ring around this puddle, with the fire extinguishers. And I went up to the galley deck, in the middle of the hangar deck, they had a temporary staircase. A big, big staircase, wooden staircase, that went, it was just temporary they would tear it down eventually. And so I ran up the staircase, got up to the galley deck and ran forward through the passageways, saw a bunch of welders, and told everyone there was a fire hazard and not to weld and all that kind of stuff. Then I went back, I was going to go back down to the deck.

And when I got to the ladder again I couldn’t see anything. It was just completely dense black smoke. I was completely blinded. You know, the fire had started. So I was able to grab onto the railing and figure out which side I was on so I didn’t go off the end. I got down to the deck, found McCartney again, he was waiting. And the place was just ablaze. I mean, it was just an inferno. And so he said, we’ve got to abandon ship. So he just told me, he said, get off the ship, get as many people as you can off the ship and so that’s what I did. I went down a couple of passageways and got off the ship to the pier.

The fire started with a leak. A large metal plate lay out on the deck; when a forklift was used to push a large metal trash can, the can unintentionally pushed the plate, sliding it underneath a 500-gallon tank of jet fuel. This fuel tank had been improperly jury-rigged to have a valve on the underside, and the sliding plate sheared it off. Fuel spilled onto the deck, and before anyone could react, it flowed into an open aircraft elevator bay, where the welding torches of the workers below set it off.

Mike also mentions a wooden staircase. Throughout the entire ship, all of the scaffolding and rigging for construction was made of wood, accelerating the fire through the main trunk lines of the ship. One of the few good consequences of the fire was that the Navy would ban wooden scaffolding from shipbuilding.

The fire took more than 12 hours to extinguish, thanks to the heroic efforts of the FDNY and shipworkers who stayed on board to rescue their compatriots. Many who made it to topside decided to take the icy plunge into the East River, 10 stories below; those who couldn’t make it out rushed to watertight compartments and sealed themselves in to escape the smoke and fire. Many were rescued by workers who listened to the sides of the ship for knocking and sparked their acetylene torches to cut the survivors out.[17]

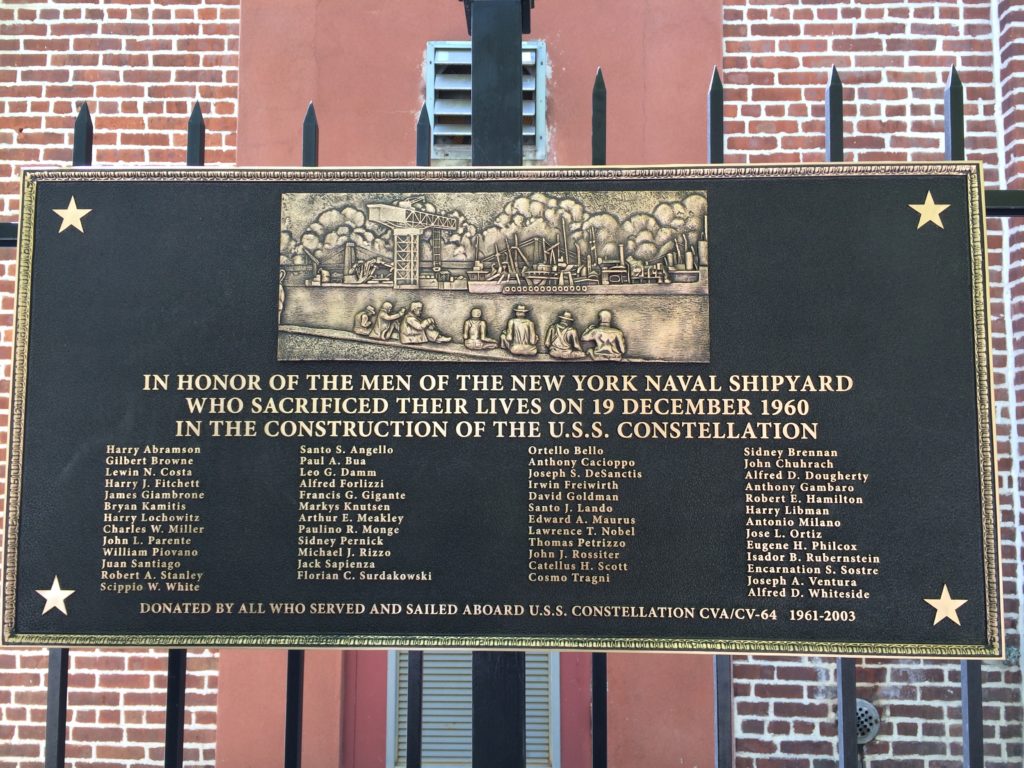

The Constellation fire cost 50 lives, all of them Navy Yard workers. The ship was ultimately completed, seven months behind schedule, but the Constellation’s hardships do not end there. During her sea trials in November 1961, another fire broke out, killing four, including two workers from the Navy Yard, machinist Alfred Steinbuch and marine engineer Eugene Miller.[18]

Another Pratt student, Bob Ochs, recalled seeing it finally finished and heading out to sea to begin its 42 years of service in the Navy:[19]

That was a clear example of what happens when things go wrong. I carried that with me for the rest of my life. In that context it was a rather extraordinary experience. Both the good and the bad. Part of the baggage that I picked up and carried. It’s kind of the vehicle that helped carry me through life. Which is a more positive way of putting it. The most positive experience was watching her sail out as a commissioned naval vessel. For me she was the best and the worst.

For the tens of thousands of sailors who served aboard Connie, one of the most important symbols was a large bronze memorial plaque dedicated to the 50 workers killed during construction, bolted next to one of the elevator bays on the hangar deck. Sometime between the ship’s decommissioning in 2003 and scrapping in 2015, the plaque went missing. So in an act of tremendous generosity, the USS Constellation Alumni Association raised money to create a (slightly modified) replica of the plaque, and donated it to the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92. Today, anyone can come by the BLDG 92 forecourt on Flushing Ave and Carlton Ave and see the names of all these workers who gave their lives in service of their country.

Below is a video of the dedication ceremony of the plaque:

[snippet slug=’bny-footer’]

Footnotes

- Long-Island Star 18 Jun 1817, p. 3.

- Long-Island Star 11 Jun 1829, p. 2.

- Stuart, Charles B. The Naval and Mail Steamers of the United States. New York: Charles B. Norton, 1853, p. 13-17.

- Long-Island Star, 1829.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle 9 Dec 1904, p. 22.

- “Buried Alive in Mud,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 7 Mar 1909, p. 1.

- “Killed in the Caisson,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 4 Mar 1910, p. 1.

- “Navy’s Biggest Dry Dock Takes Seven Years to Build,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 7 Aug 1910, p. 13.

- “More Delay in Sight for Big Dry Dock No. 4,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 4 Nov 1909, p. 2.

- “Another Victim of Dock,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 9 Jun 1911, p. 2.

- “Navy Yard Laborer Dies,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 30 Oct 1911, p. 20.

- “Edison Lessens Submarine Peril,” New York Times 18 Apr 1915.

- “Hydrogen Leak Suspected,” New York Times 16 Jan 1916.

- “98 Years Ago the E-2 Blows Up in Dry Dock,” The USS Flier Project.

- “Nearly Loses Hand in Engine He Built,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle 20 Nov 1916, p. 18.

- Michael DeLucia oral history interview, 21 Sep 2014.

- “Fuel Tank Ignites,” New York Times 20 Dec 1960.

- “4 on Constellation Killed in New Fire During Test at Sea,” New York Times 7 Nov 1961.

- Robert Ochs oral history interview, 5 Nov 2012.