They say a Navy ship has three birthdays: its keel-laying, its launching, and its commissioning. The World War II-era battleship USS Missouri has one more, its recommission in 1986 as part of President Reagan’s 600-ship Navy. But one person was witness to its first two birthdays, Brooklyn Navy Yard shipfitter Clayton Colefield, who sat for an oral history in 2009 with Sady Sullivan of the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Born in 1921 in Jamaica (the island, not Queens) to an English father and a Spanish mother, his seafaring family settled in the Bronx in 1926. After graduating high school, he struggled to find work in the midst of the Great Depression, but eventually caught on as a machinist at a factory in Lower Manhattan, and in 1940, he heard they were hiring at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Because of his experience, he was made an instructor, and then a “quarterman,” a shipyard term for a supervising foreman. He explains how he earned this responsibility:

I was instructing people how to put stuff together and parts together because I could read the blueprints and tell them where the parts went. So anyway, so the ships were built in sections, and the sections were built in the shops in the huge covered areas. The shops were very large and big. They could hold huge sections of material, and very high so they could build them, high stuff if necessary. And they were transported out to the, out to the dry dock and out to the what they called the ways where the ships were built at one time before they built them in dry docks.

On January 6, 1941, Clayton had the honor of supervising the crew that laid the first keel plate for the Missouri, a 45,000-ton battleship that would take three-and-a-half years to complete. Usually occasioned by a lot of pomp and ceremony, the keel-laying was a big photo op for the top brass, and the honor of putting the first rivet in the keel (actually, starting the machine that drove the rivet) was given to the Yard’s Commandant, Rear Admiral Clark Woodward, but it was Clayton’s crew that did the heavy lifting.

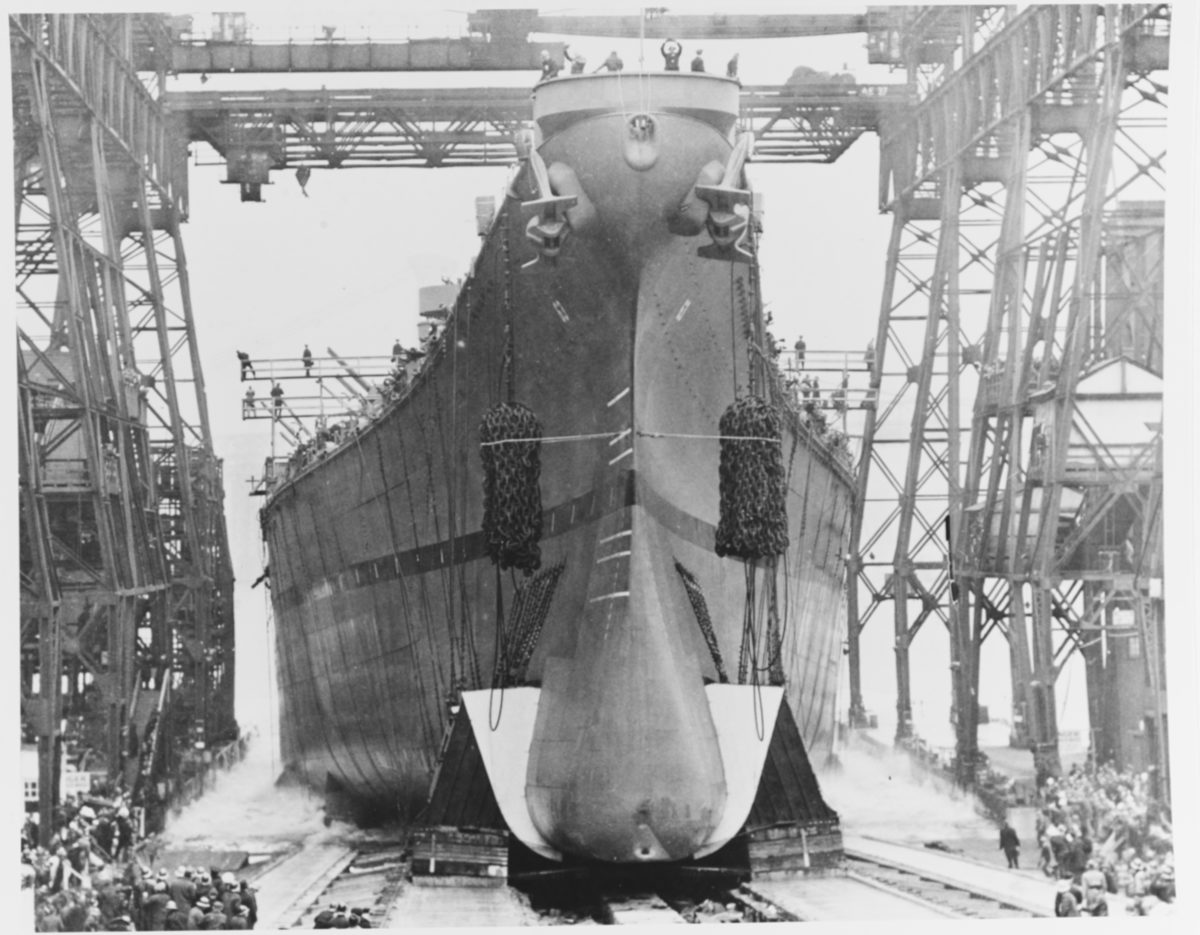

More than three years later, on January 29, 1944, Clayton was there again, for the launching of the battleship, christened by the daughter of the US Senator from Missouri, Harry S Truman.

We stood up on a big platform on the bow of the ship, and then they christened it with the champagne, and then they turn on the hydraulic jacks. And the ship is on the ways, and in cradles, and the cradles are built so that they slide on a lubricant, all the way down from where it is right into the water. So when the lady – I forget who that was [Mary Margaret Truman] – broke the bottle, they turned on the hydraulic jacks and the ship started to move all the way down to the water. That was an experience. Big splash. And then the tugboats took hold of it and they brought it over to the hammerhead crane, where they, where we worked on it. … It was, exultation, you know, something you did and it sailed. It didn’t sink. … You know, it floated, you know, it was an experience. You wouldn’t think all that weight could be held up in the water, but it did.

Clayton does not mention the commissioning the following July in his oral history (he did a stint in the Army at some point during the war as a technician), and was at the Yard through the end of the war, when the Instrument of Surrender was signed by Japan on Missouri’s deck. Unlike three-quarters of the workers at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, who were laid off, Clayton got to stay on, working until 1965. During his 25 years of service, he worked on many ships, though none as famous as Missouri.

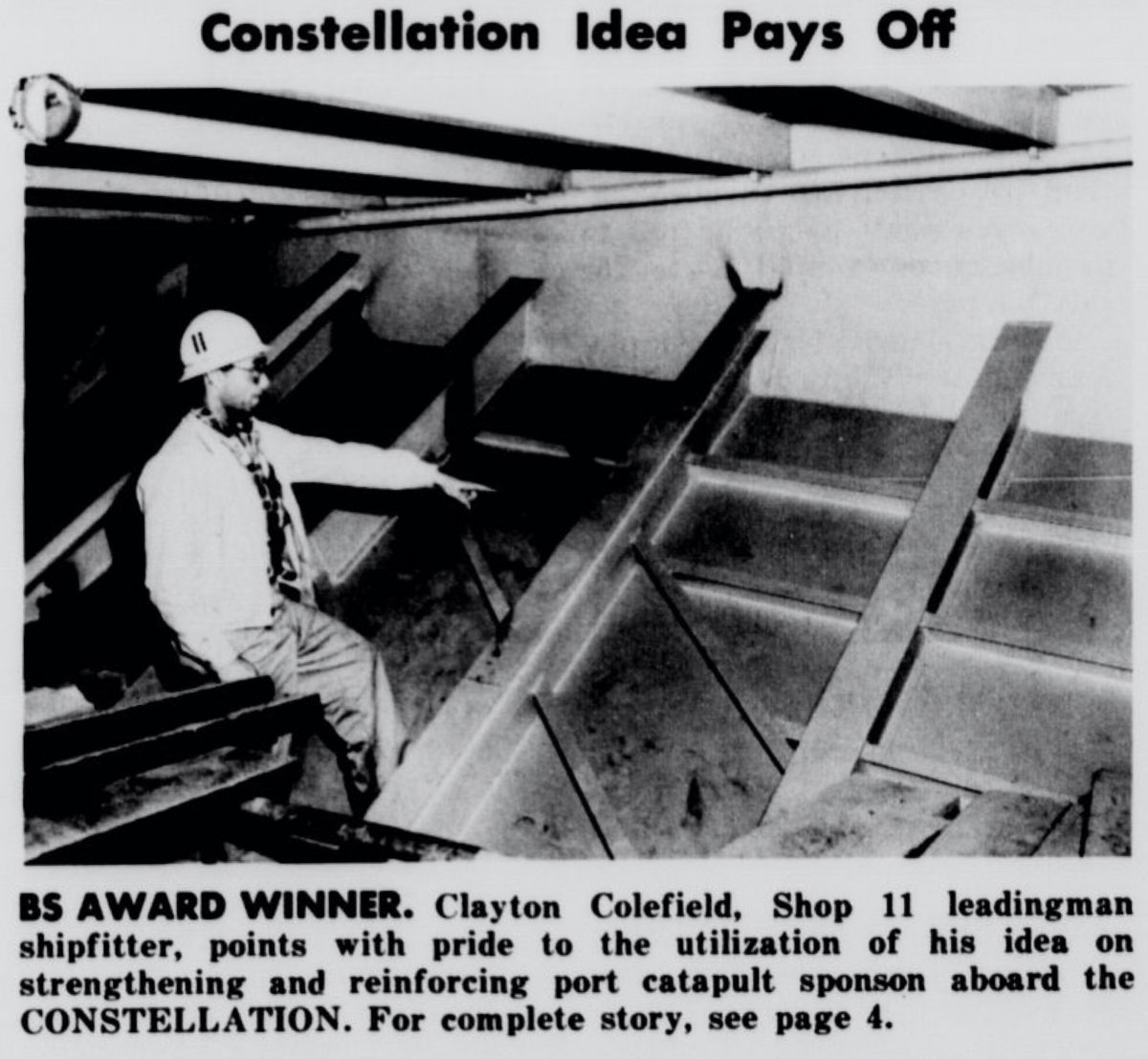

Over the years, Clayton was mentioned several times in the Shipworker newspaper for his “beneficial suggestions,” reaping $207.50 in bonuses noted in the paper. One of his suggestions was to reinforce the sponsons holding up the flight deck catapult of the carrier USS Constellation, where he was working in May 1961; because we working nights, he had avoided the deadly fire five months earlier that killed 50 of his coworkers.

After leaving the Yard, he went on to become a high school teacher, teaching industrial arts for 19 years. Clayton passed away in 2012. In June 2019, we were joined on a tour of the Yard by several of his relatives, and we were able to share his oral history and recollections of the Missouri with them.