September 2 marks the 70th anniversary of the official end of the Second World War, when Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender in Tokyo Bay in 1945. While we are marking the event today, the actual anniversary took place at around 8pm on September 1, Eastern Standard Time. The largest celebration of the event in the world was held in Beijing, and has long since finished; the major commemoration of the event in the US will take place at 3pm EST in Hawaii, aboard the USS Missouri, where the original surrender took place.

Last year, we examined the connections between the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the event that brought the United States into the war, the attack on Pearl Harbor. Today, we will look back at our close ties with the war’s end.

The fact that the surrender ceremony was held on board the Brooklyn-built USS Missouri is an obvious connection. But I would rather look at another artifact of history – a small, modest flag that hung in the background of this momentous event.

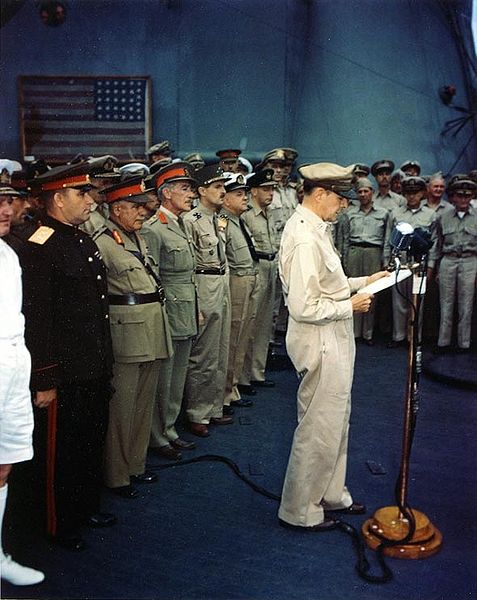

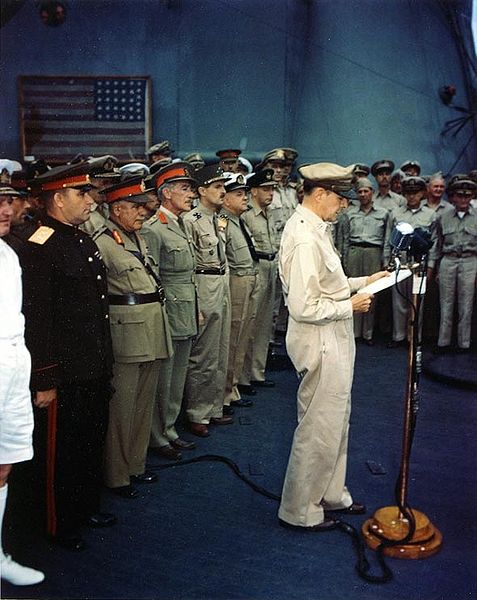

Japan had officially surrendered to the Allies on August 15, but it took weeks of preparation to amass the occupation forces and bring together the principal actors in one location for the official ceremony. The event was orchestrated by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who was named commander of Allied forces in occupied Japan, and his naval counterpart, Adm. Chester Nimitz. President Harry Truman, though he did not attend, did provide important input – he insisted that the battleship Missouri, named for his home state, be the site of the surrender. Other ships had been considered, including the battle-tested carrier Yorktown and Missouri’s sister ship Iowa, as the Missouri had only been in action for a little over a year. But Truman had attended its launch from the Brooklyn Navy Yard in January 1944, and his daughter Margaret had christened it; the ship would be a stand-in for the president.

The crew of the Missouri was informed of this special honor only a few days before the ceremony. In a recent article published in the US Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine, “Mighty Mo’s” captain, Stuart S. Murray, recalls the preparations, as told in an oral history recorded for USNI in 1974. With no time to make a port call, everything had to be done at sea, including repainting decks and bulkheads; despite the fact that paint, being highly flammable, was strictly prohibited aboard Navy ships, they managed to cobble together a few buckets from their stores and from other ships. Once they knew the roster of attendees, sailors stood in for the dignitaries, practicing the movements of the ceremony down to second; one sailor even used a mop handle shoved down his pants to mimic the movements of the Japanese foreign minister, Mamoru Shigemitsu, who had a wooden leg.

The Missouri did not sail into Tokyo Bay alone. In fact, a flotilla of more than 250 Allied ships, including vessels of the British, Australian, and New Zealand navies, would join her, as well as ships of the Japanese Imperial Navy, their guns lowered and visibly plugged in a signal of surrender, to direct the occupiers away from underwater mines and submarines. Of this vast armada, only two ships had been present at Pearl Harbor, the battleship West Virginia, and the cruiser Detroit, a testament to the complete transformation and modernization of the US Navy in less than four years of war. Also among the flotilla were Brooklyn Navy Yard products Iowa and New Mexico, as well as the battleship South Dakota, which had undergone a two-month overhaul at the Yard after nearly being sunk at Guadalcanal.

Among Gen. MacArthur’s exacting demands for the ceremony were that his ensign, the flag of a five-star general, be flown from Missouri at the same height as also-five-star Adm. Nimitz’ flag, requiring the welding of an additional flagpole onto the ship’s topmast. But MacArthur also insisted that another flag be present for the ceremony, one that had been brought to Japan 92 years earlier.

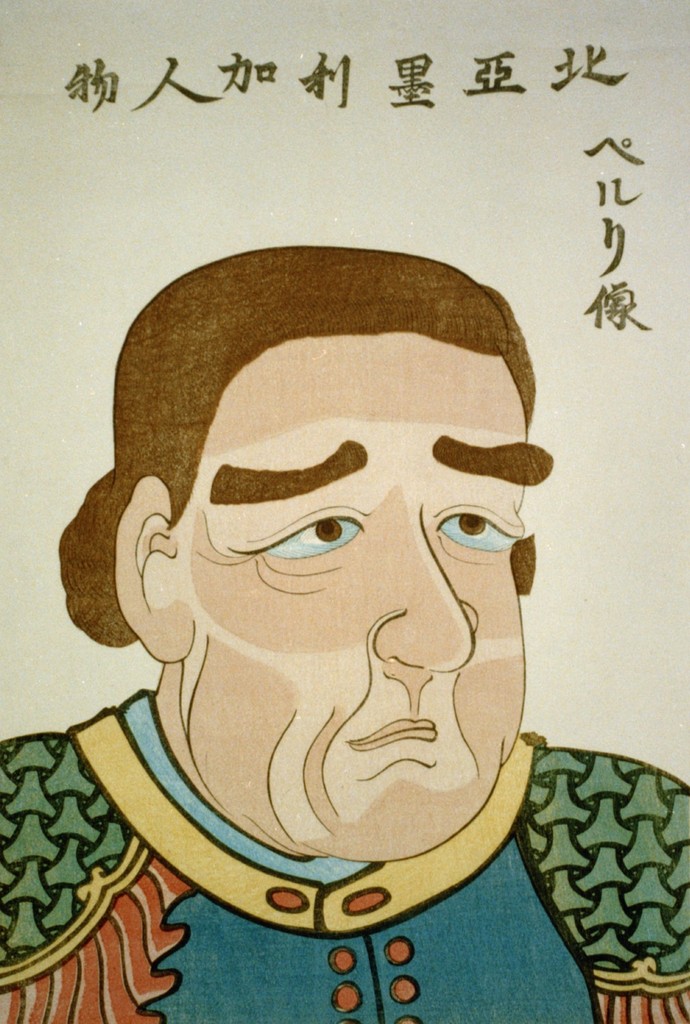

In November 1852, Commodore Matthew C. Perry set out from Norfolk, VA as commander of the East India Squadron. Aboard his flagship, the paddle-wheel steam frigate Mississippi, he carried a letter from President Millard Fillmore, addressed to the Emperor of Japan. Perry’s mission was to deliver this letter and open diplomatic and trade relations with a country that had been almost completely closed to outside contact for more than 200 years.

Perry is probably the most famous sailor with deep ties to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. From 1833 to 1837, we oversaw construction of the first steam-powered warship of the US Navy, the USS Fulton, at the Yard, during which time he also helped found the Navy’s first institution of higher learning, the Naval Lyceum, created the Navy’s first (short-lived) apprentice system, and served as the Yard’s second-in-command. By 1841, he himself had become the Brooklyn Navy Yard commandant.

Perry’s fleet, dubbed the “Black Ships,” much smaller than the Allied force in 1945, entered Tokyo Bay in July 1853, where they were greeted with great suspicion and interest. After several days of negotiations with local officials and representatives of the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate – the real power in Japan behind the figurehead emperor – Perry and a force of 400 sailors and marines were finally allowed ashore to present their letter to the Japanese. Rather than wait for an immediate response, Perry took his ships to Hong Kong, then returned in February 1854 to commence negotiations. After six weeks of talks – and demonstrations of American power and technical prowess, including a small locomotive and a telegraph machine – Japan agreed to allow American ships to trade with Japan, to furnish US Navy ships with fuel and provisions, and to provide safe harbor to American vessels in distress. The Treaty of Kanagawa marked the end of Japan’s 220-year-old sakoku period of isolation, and positioned the United States as an up-and-coming Pacific power.

Shortly after his return to America, Commodore Perry presented the 31-starred American flag from his expedition to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, where it was put on display (and still hangs today – a replica of the flag has been placed aboard the Battleship Missouri Museum). 90 years later, MacArthur felt that it would be a fitting artifact to display aboard the Missouri, especially considering that Perry was a distant relative. A courier was dispatched from Annapolis to carry the flag, which had been sown to a linen backing and framed in a glass case, to Japan. The trip took reportedly took five days, but the flag was delivered in one piece. Due to its framing, the flag was actually hung backwards, as you can see in the photo above.

MacArthur made the connection between Perry’s visit and the American return to Tokyo Bay in his remarks at the surrender ceremony – you can read the full text of his speech here:

“We stand in Tokyo today, reminiscent of our countryman, Commodore Perry, 92 years ago. His purpose was to bring to Japan an era of enlightenment and progress by lifting the veil of isolation to the friendship, trade, and commerce of the world. But alas, the knowledge thereby gained of Western science was forged into an instrument of oppression and human enslavement.”

Through the centuries, this small artifact has represented the ties between the United States and Japan, in peace and in war, and something worth remembering on this solemn day.

The “Can-Do” Yard: World War II and the Brooklyn Navy Yard Tour is offered monthly. The next tours will be on September 6, October 4, November 8 and December 6, 2015 – please visit our tour page for information and to purchase tickets. Advance ticket purchase is recommended, and this tour is offered free to all World War II-era veterans and defense workers. We also offer our Past, Present & Future Tour of the Brooklyn Navy Yard every weekend, as well as other theme-based tours. All tours are offered in partnership with and begin at the Brooklyn Navy Yard Center at BLDG 92, which offers free admission to three floors of exhibitions on the yard’s past and present, and a host of great special events and programs.