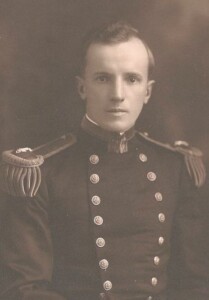

Frederick Louis Riefkohl (1889–1969)

The histories of Puerto Rico and of the US military are deeply intertwined, and much of that history runs through the career of Frederick Louis Riefkohl, the first Puerto Rican to graduate from the US Naval Academy, to win the Navy Cross, and to achieve the rank of rear admiral. Normally we would not consider someone from Puerto Rico an immigrant – they are US citizens – but Reifkohl lived in a complicated time.

Riefkohl was born in Maunabo, on Puerto Rico’s southeast coast, in 1889. Born a subject of the Spanish crown, his family was descended from German immigrants who settled in Puerto Rico throughout the 19th century. In 1825, having lost most of its American colonies and still desperately clinging to Puerto Rico and Cuba, Spain encouraged immigrants from all over Europe to settle on the islands. Riefkohl’s father was born in Puerto Rico, the child of immigrants from Germany and Switzerland, while his mother was born in Germany and emigrated, first to the Danish possession of St. Thomas, then to Maunabo.

In 1898, the United States wrested control of these islands, as well as the Philippines, in the Spanish-American War. Puerto Rico would become a US territory, but residents did not immediately become US citizens. It was in this period of limbo that Frederick would be sent to the US for his education, attending private schools in New England, and then in 1907, receiving an appointment appointed to the US Naval Academy from President Theodore Roosevelt himself. He followed in the footsteps of his brother Rudolph, who attended MIT and received a commission in the US Army. Graduating in 1911, his first assignment would be to the newly-built battleship USS Florida, constructed and commissioned at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, one of his first professional encounters with the Yard.

Despite receiving his naval commission, Riefkohl was still not a US citizen; he would have to wait until 1913, when a special act of Congress granted him citizenship. The rest of his countrymen, however, would have to wait another four years, when America entered World War I. The Jones-Shafroth Act, enacted on March 2, 1917, granted US citizenship to all Puerto Ricans. While the law did solve the problem that Puerto Ricans lacked any internationally recognized citizenship, one of the principle motivations for the law was to allow Puerto Ricans to be drafted into the US military. Just two months later, the US entered the war, and more than 18,000 Puerto Ricans would serve in uniform.

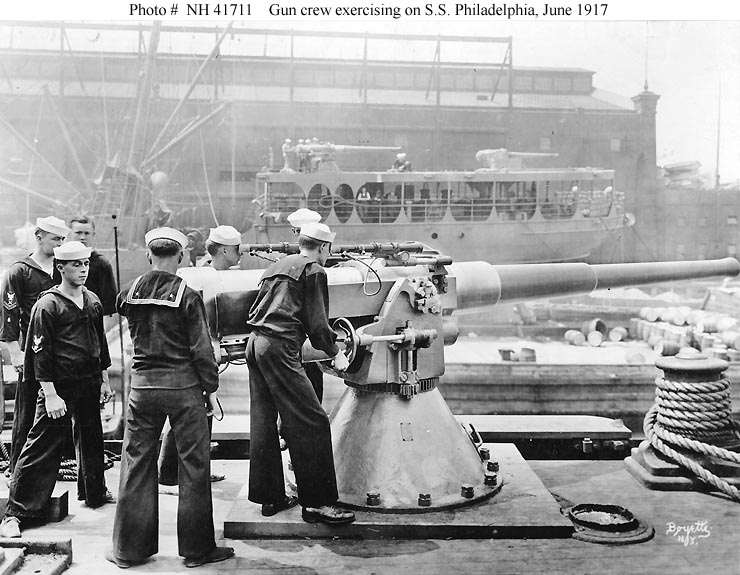

It was during World War I that Riefkohl would first rise to prominence. In the very early days, then-Lieutenant Reifkohl was assigned a somewhat unusual duty, aboard a passenger liner. The SS Philadelphia,* owned by the American Steamship Line, had been pressed into duty as an Army transport. These converted ocean liners were crewed by civilian mariners, but they were also outfitted with guns, which were crewed by Navy sailors known as an Armed Guard, for defense against German U-boats. It was during this assignment that Riefkohl would earn the Navy Cross, as his citation notes:

For distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commander of the Armed Guard of the U.S.S. Philadelphia [sic], and in an engagement with an enemy submarine. On August 2, 1917, a periscope was sighted, and then a torpedo, which passed under the stern of the ship. A shot was fired, which struck close to the submarine, which then disappeared.

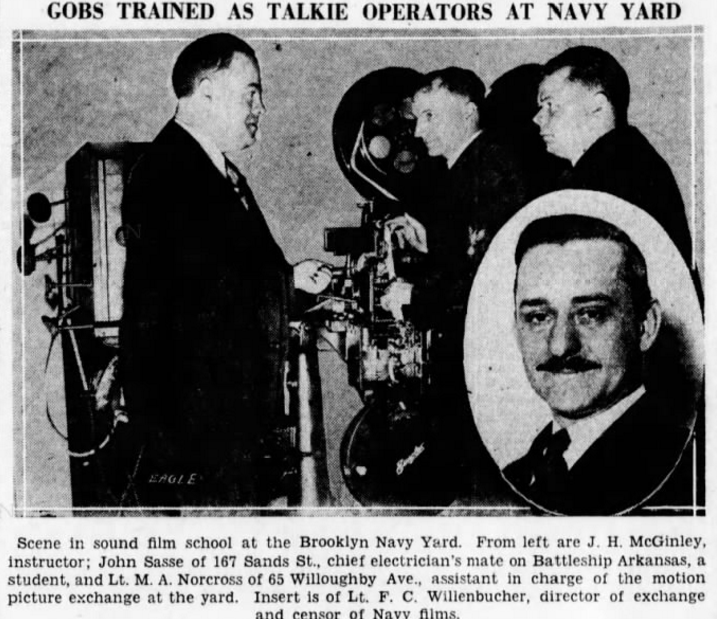

Following the war, Riefkohl received many assignments in radio communications, including in September 1924, when he was assigned to the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a Radio Material Officer. He would return to the Brooklyn Navy Yard exactly ten years later, this time as the Officer in Charge of the Yard’s massive Motion Picture Exchange. Established in 1919, the exchange had been the largest distributor of silent films in the country, with 20,000 reels of feature films, training films, and newsreels in circulation. In 1931, the Navy transitioned to “talkies,” and the exchange spearheaded the installation of new sound equipment across the fleet. At the time of Riefkohl’s appointment, the exchange, like the Navy, was probably rather sleepy. The Navy purchased only two copies of new releases to distribute across the entire service; by 1942, they would be purchasing 23, distributing more than 6,000 feature film prints around the world from the Brooklyn office, and training sailors to safely operate the projectors on ships and battlefields across the globe.

With World War II came a new assignment for Riefkohl, and on April 23, 1942, he was given command of the cruiser USS Vincennes. After taking part in the pivotal Battle of Midway in June, the ship spent a month in Pearl Harbor for repairs, then joined the invasion force headed to Guadalcanal, a key Japanese airfield in the Solomon Islands. On August 7, Vincennes conducted shore bombardments to cover the landing of US Marines, and the following day provided anti-aircraft cover. That night, Vincennes and the cruisers Quincy and Astoria turned north to intercept a Japanese force headed for the island. The ensuing Battle of Savo Island would send all three to the bottom. Vincennes engaged the enemy around 1:45am on August 9, and the Japanese force was similar in size. However, the Japanese were much more skilled in night fighting than their counterparts, and the American officers and crews were unprepared for the ferocity of the battle that would ensue. Just one hour later, the VIncennes was sunk, with the loss of 332 sailors. That would be the last ship Riefkohl ever commanded.

For the rest of the war, Riefkohl would serve as a staff officer, taking assignments in Mexico City, Miami, and New Orleans. The final assignment of his career would bring him home, as commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier, headquartered in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He retired from the Navy in 1947, and passed away in 1969. He is buried in the cemetery of the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. His remarkable career began a long connection between Puerto Rico and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which has grown over the past century. In the decades following World War II, many Puerto Ricans settled in Williamsburg, just outside the gates of the Yard. Today, despite tremendous development, this remains one of the largest Puerto Rican neighborhoods in New York City, and many people from this community continue to work in the Yard’s many businesses.

* Note: Several sources, including Reifkohl’s official Navy Cross citation, mistakenly note the ship he served on as the “USS Philadelphia.” In 1917, there was a commissioned warship in the US Navy by that name (protected cruiser C-4, built in 1890); however, it was stationed as a receiving ship at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, not operating in the Atlantic. The SS Philadelphia was built in 1888 as the SS City of Paris. In 1898, it was acquired by the US Navy and commissioned as USS Yale for the Spanish-American war (and incidentally operated off of Puerto Rico). It returned to civilian service in 1899, and was renamed SS Philadelphia in 1901. In May 1917, the ship was pressed into service as an Army transport – the period during which Riefkohl commanded the Armed Guard – and it was acquired by the Navy again in May 1918, commissioned as USS Harrisburg. Of all the sources that we have examined, only A Log of the Vincennes (1947) includes this accurate description in its biography of Reifkohl.