The Brooklyn Navy Yard has been a place of refuge for much of its history. During its 165-year run as a naval shipyard, it did not just send ships down the ways and off to war; it took in ships in the most desperate, hopeless shape, and put them back into fighting order. During World War II, more than 5,000 vessels were steamed, limped, towed, and dragged into the safe waters of Wallabout Bay to be tended to by the 72,000 men and women of the yard.

Of all the wounded ships to steam up the East River, none were more so than the aircraft carrier USS Franklin.

The Franklin was recently in the news – on May 17, the alumni association of the ship’s crew held a reunion at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Charleston, SC. Twenty-one survivors attended the event held aboard the USS Yorktown, a World War II Essex-class carrier like the Franklin that is now a museum ship. The “Fighting Lady,” as the Yorktown is known, even changed her markings for the occasion, swapping the “10” on her side for the Franklin’s hull number of 13. The association has said that this will be their final reunion, due to their membership’s advanced age and dwindling numbers, but they received an honorable and moving dedication. Everyone who served aboard the Franklin is a World War II veteran – built in Newport News, VA and commissioned in January 1944, “Big Ben” saw just 15 months of service in the Pacific theater, yet in that time it amassed more decorations – and more casualties – than nearly any other ship in the American fleet.

The saga of the Franklin is filled with heroism and tragedy, triumph and betrayal. Her trials began in the waters of the Pacific, and they reached their final chapter in the slips of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She took her first big hit on October 15, 1944, when she was struck by a Japanese kamikaze attack off the Philippines. The suicide pilot slammed into the ship’s flight deck at 400 miles per hour, opening up a 40-foot hole and killing 56 crewmen. But the Franklin survived, and headed to Puget Sound Naval Yard to be laid up for two months of repairs.

Despite surviving this tremendous blow, it was the second attack on the Franklin that would solidify its unsinkable reputation. She returned to action in February 1945, and on March 19, she sat just 50 miles off the coast of the Japanese home islands, launching daily sorties against the mainland. Early that morning, with dozens of planes fully fueled and loaded for missions, a single Japanese bomber penetrated the Franklin’s air defenses and dropped a 550 lb bomb on the rear of the flight deck. The direct hit plowed into the hanger deck below and exploded, setting off a chain reaction as aviation fuel and munitions ignited. A firestorm quickly erupted throughout the bowels of the ship, and hundreds of the men who were below decks having their breakfast found themselves trapped.

Confusion reigned as the Franklin lost radio communication and its crew scrambled to escape the thundering explosions as ammunition and bombs fired off around them. Men who were able rushed to the flight deck to fight the fires and tend to the wounded. Many who could not reach the deck ran to the fantail at the stern, where their only option was to leap overboard. Other ships quickly rushed to Franklin’s aid. The Santa Fe began plucking sailors out of the ocean and plying water on the fires, which caused the stricken ship to list to starboard some 13 degrees. Many men thought they had heard orders to abandon ship, and they leaped into the water or across the Santa Fe. The Franklin seemed destined for the bottom, but nearly 10 hours after the attack, the fires were mostly contained. When a muster was called, only 275 of the ship’s 3,400 men were counted – the rest were either dead, in the water, on board other ships, or still trapped below decks.

The Franklin was eventually towed to Pearl Harbor, but due to the extent of the damage, and the lack of capacity at the already strained Pacific coast shipyards, the ship was to be taken to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for repairs. She then embarked on one of the most amazing journeys of the war, steaming 12,000 miles through the Panama Canal and up to New York Harbor under her own power with less than one-third of her normal complement of men, and still listing sharply to starboard.

When she arrived at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in late April 1945, many of the workers came out to watch the battered ship. It was not until May 17 that the public knew anything of the attack or the ship’s epic journey, as wartime censorship kept it out of the press. The Navy Yard’s weekly newspaper The Shipworker asked in its October 30 issue, “What was your most inspiring experience during the war years in the Navy Yard?” Stephen J. Hudson had this to say:

Witnessing the return of the battle scarred carrier “FRANKLIN.” In the course of my work I had the opportunity to board the “FRANKLIN” and observe the terrific damage sustained. Words, regardless of how eloquently or descriptively uttered by a speaker, could not portray more realistically the scenes I witnessed. Only then, could one visualize the sacrifices made by her gallant crew and the insignificant role played by us at home.

Sol Feinstein, who was interviewed as part of the Brooklyn Navy Yard oral history project, worked building engines during the war. He had a sobering experience when he let his curiosity get the better of him as he walked by the Franklin.

They had men with the acetylene torches cutting away certain parts that were distorted and destroyed. And I’m sorry to say one day I got curious and went over to one of these 55-gallon drums … it’s standing on one side, and the top part of it is was opened – the lid was off of it. And some of them still had live amun- ammunition that they found there. They found little, I don’t know what they were, shells that were still live, that could go – could detonate. And they would throw it into this container with water as a precautionary measure and keep it safe. And one container contained some limbs. I lost my appetite.

Despite the best efforts of her skeleton crew on the cruise home, the Franklin remained a floating graveyard when she arrived in Brooklyn. All told, 807 men lost their lives on March 19, and many of them would remain entombed in the ship’s hull until she was finally broken up for scrap more than 20 years later. 926 men died aboard the Franklin during her brief wartime service, ranking it behind only the USS Arizona (a Brooklyn Navy Yard-built ship), which lost 1,177 men at Pearl Harbor, for the most casualties of any ship in the war.

Despite the feverish work of the Navy Yard’s workers, the Franklin would never see action again. Japan surrendered in August, and the peace treaty was signed aboard the battleship Missouri (another BNY product), on September 2, 1945 in Tokyo Bay.

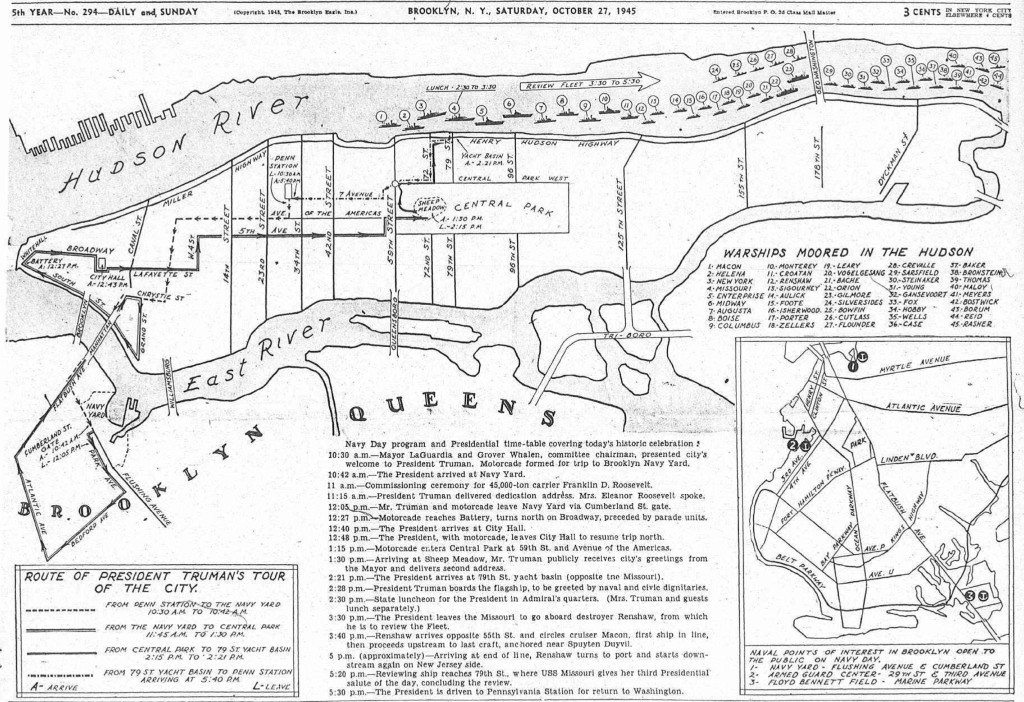

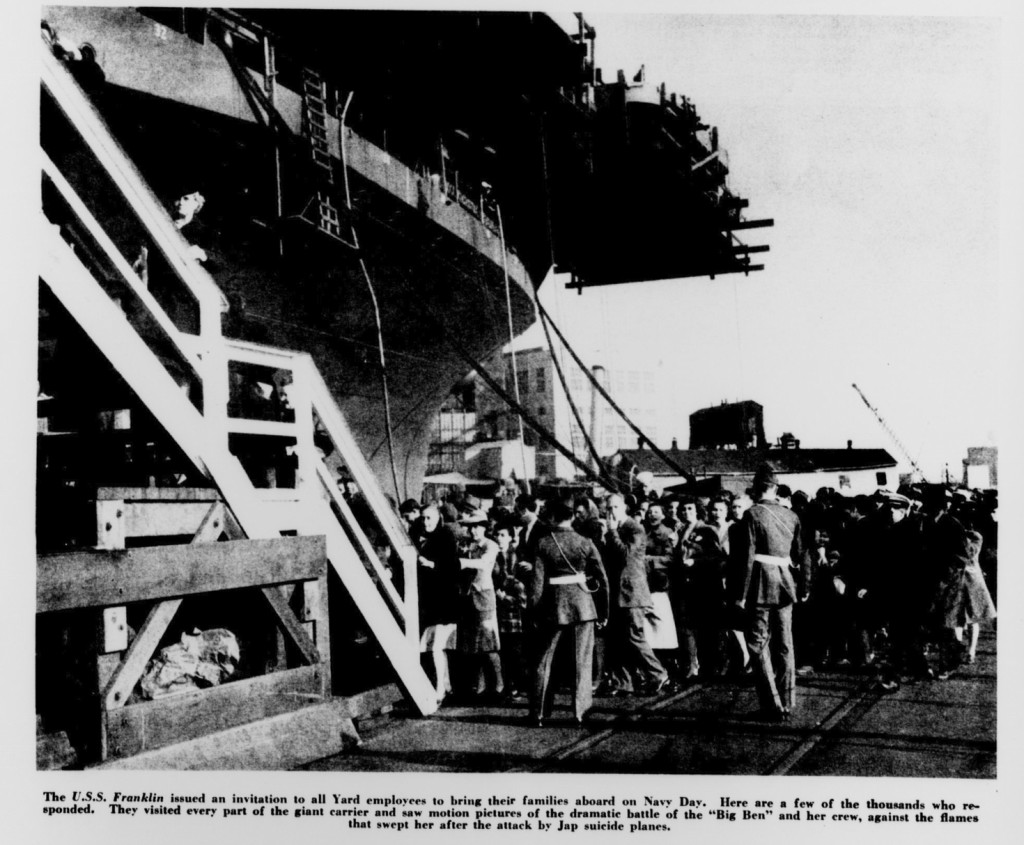

Following the war, October 27 was a banner day in New York City. Navy Day was marked with a massive flotilla, as 45 ships lined the Hudson River for a presidential review, and 1,200 aircraft flew overhead. At the Brooklyn Navy Yard, President Harry Truman and Eleanor Roosevelt commissioned the fleet’s newest carrier, the 45,000-ton Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the ship’s invocation was offered by Joseph T. O’Callahan, the chaplain of the Franklin who earned the Congressional Medal of Honor (one of two earned by the crew – the other went to Donald Arthur Gary, who led hundreds of men from the fires below decks to safety) for his heroism tending to wounded men in the midst of the attack. And nearby sat his ship, still battered, but cleaned up enough to allow yard workers and their families – 20,000 visitors in all – to walk the flight deck and inspect the extent of the damage for themselves.

New York City will not have a Fleet Week this year – a casualty of the budget sequester – but as we look back at this triumphant fleet thundering into the harbor, we will think of the Franklin, which sat humbly in her berth, a silent reminder of the tremendous sacrifices of the men who served. We hope you, too, will remember these men, and all the other men and women who have given as much, as we approach Memorial Day.

A newsreel about Navy Day 1945 in New York.

To learn more about the saga of the Franklin, check out Joseph A. Springer’s book Inferno: The Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II, which provides a much more comprehensive look at the Franklin’s career than I can here, much of it told by the men who lived through it. This short film put out by the Department of the Navy in 1947 also chronicles the ship’s brief but eventful career.

[snippet slug=’wwii-footer’]