On Thanksgiving, we’re looking back at an unsung hero of the holiday during World War II, a merchant ship called SS Great Republic. This ship helped execute the great turkey-lift of 1944, delivering turkey to nearly two million American soldiers fighting in Europe. As we’ll discover, delivering this meal stretched the military’s supply chain, and the New York Port of Embarkation, to its limits.

The Problem

American troops had been pouring into northwest Europe since D-Day, but progress towards Germany was slower than expected. There was no way the war would be over by Christmas, as was the optimistic prediction in June. In September, American commanders promised a full, fresh turkey dinner for the coming Thanksgiving—no canned turkey for America’s fighting men. This was a tall order, as there were already 1.3 million troops on the continent, and a half-million more would arrive by the holiday.

The problem with delivering on this promise was three-fold: inadequate ships, inadequate ports, and inadequate ground transportation. The Allied “cold chain”—the temperature-controlled supply lines that would have to extend from American turkey farms to GI messes on the German border—was not up to the task.

The Allies had long faced a shortage of “reefers,” or refrigerated ships. In 1943, the Maritime Commission, which managed civilian ship construction and operation, had ordered a series of five refrigerated cargo ships: Trade Wind, Flying Scud, Blue Jacket, Golden Eagle, and Great Republic. Built by Moore Dry Dock in Oakland in the C2-S-B1 (R) configuration, they were all operated by the United Fruit Company. This would help alleviate the shortage, but five ships could not supply nearly two million men, so they relied on older, smaller, slower ships as well to carry frozen cargo.

Issues at the ports in France further exacerbated the ship shortage, as there was insufficient cold storage space, and not enough refrigerated trucks and railcars to move supplies to the front. Once a shipment got held up in a refrigerated warehouse, it had knock-on effects across the whole supply chain, as ships could not unload in a timely manner, leading to altered sailing schedules and frequent spoilage. Add to this the fact that the supplies and warehouses were the responsibility of the Army Quartermaster Corps, while the ships, trucks, and trains were operated by the Army Transportation Corps (though the ice that went into the trucks and trains had to be managed by Quartermasters), and it caused serious communication breakdowns.

The Solution

Military leaders feared that the damage caused to morale by not delivering on the Thanksgiving promise would be far more costly than trying to squeeze a million turkey dinners into this creaking supply chain. So starting in September, fresh meat, vegetables, and fruit were drastically cut out of rations, and more non-refrigerated smoked and cured meats were introduced. Cutting refrigerated shipments was risky, as planners feared that if they cut shipments drastically, the British would ask to return the unused cold storage space in the UK to civilian use, and the US Army would not be able to get it back later. Turkeys also posed a particular challenge because of their shape and bulk; they took up 50% more storage space than beef or pork, and more of their weight was inedible bones.

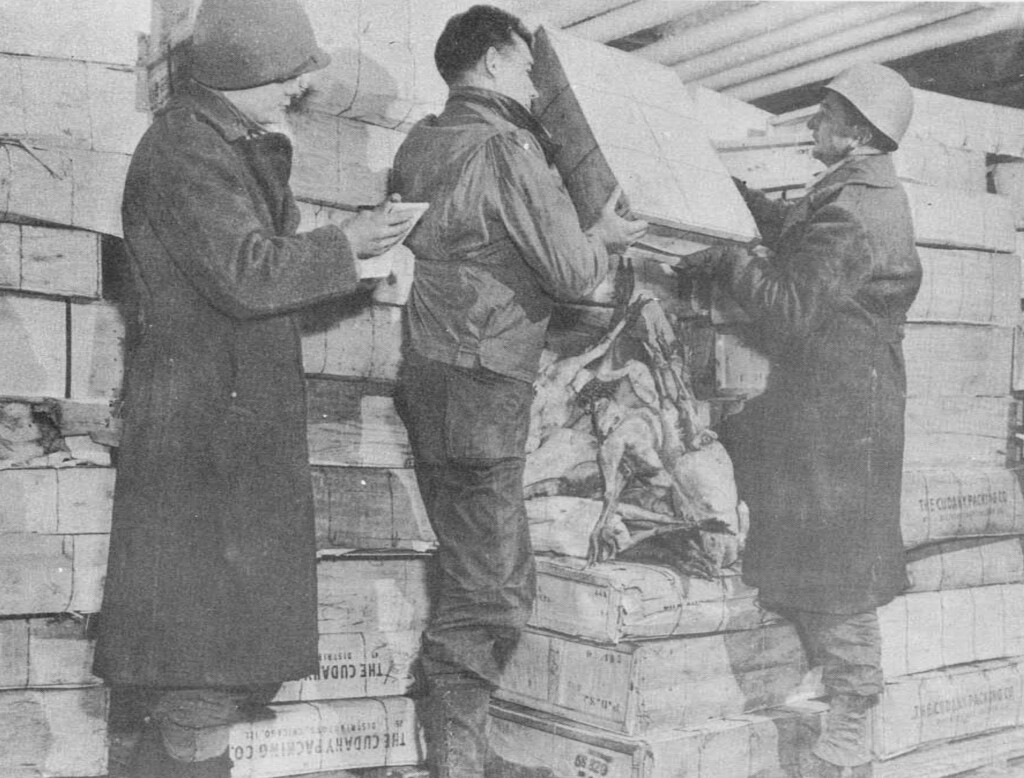

The stage was set for the arrival of the Thanksgiving feast. SS Great Republic departed New York on October 15 carrying 1,604 tons of frozen turkey, arriving in Liverpool 10 days later, then in Le Havre on November 16. This one ship would carry the entire Thanksgiving supply, enough for more than one million meals. In anticipation of their arrival, a fleet of trucks had been assembled, some commandeered from mobile bakery units, others simply flatbed trucks with tarps that would speed the frozen cargo to units within 100 miles of the port.

The Meal

Most of the turkeys cooked in the field were roasted in the M-1937 field range, a gasoline-fueled oven that could handle a 16-pound bird. The menu included 1.5 pounds of turkey per man—three times the meat of a normal “A” ration—plus stuffing, mashed potatoes, string beans, corn, cranberry sauce, celery, hot rolls, and pumpkin pie. Not every GI got a turkey dinner on Thanksgiving day—some got a day or two early, some late, but nearly everyone did within two days of the holiday, a tremendous organizational achievement.

While the mission pushed the limits of American logistics, it also underscored its deficiencies, and huge improvements had been made by the time Christmas rolled around, helped by the liberation of much larger port facilities at Antwerp. For that holiday, the Army was much better prepared to deliver a celebratory feast in a war zone; unfortunately, few American troops would get a hot meal on Christmas, as the Battle of the Bulge raged, and most could only dream about that hot, fresh Thanksgiving turkey.