On June 9, 2018, Reinhard Hardegen, the last surviving German submarine commander of World War II, died at the age of 105. With his passing, he joins the ghosts of American merchant mariners who still haunt Manhattan’s Battery Park.

Dedicated in 1991, the American Merchant Mariners’ Memorial was created by sculptor Marisol Escobar as tribute to the 9,000+ American Merchant Mariners killed in the war. The Merchant Marine provided a vital service to the war effort, shipping troops and supplies across some of the deadliest seas in the world. American mariners received fire from the enemy, and they returned fire, as many merchant vessels were armed, while suffering the highest casualty rate of any service branch in World War II.

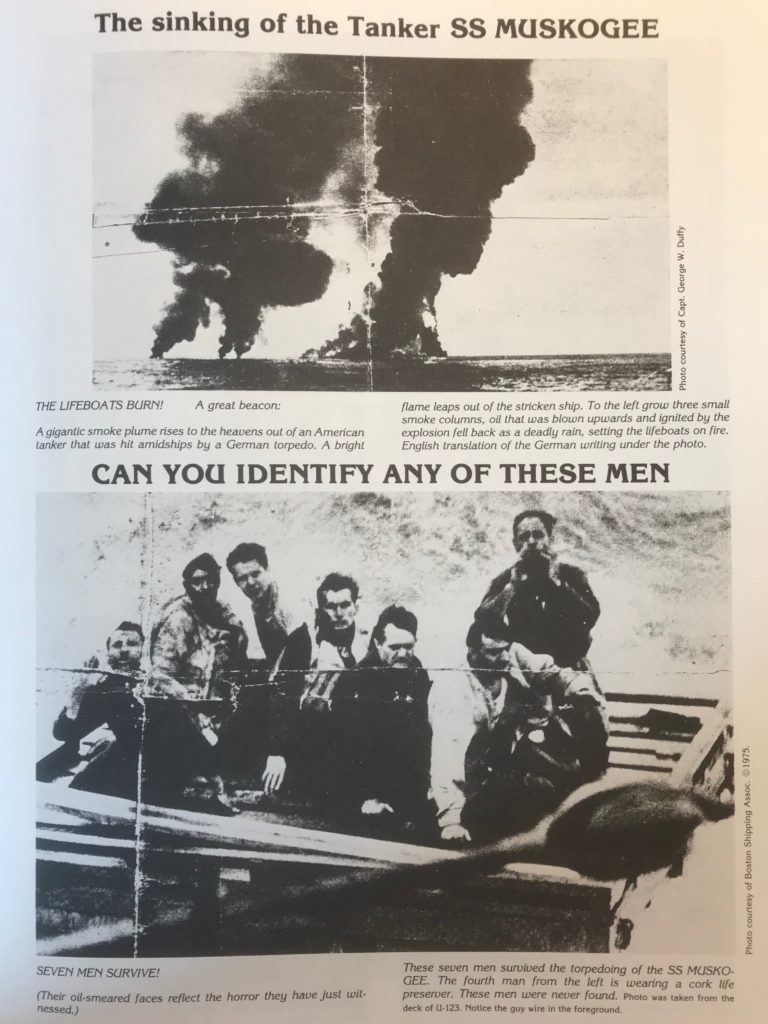

When conceiving of a tribute to these brave men, Escobar was inspired by a photo she saw of seven men marooned on a makeshift raft in a vast ocean. That photo has a direct connection to Hardegen, and we set out to learn more about it and the events surrounding it.

The man who attacked New York

Hardegen was the commander of U-123, one of five German U-boats assigned to Operation Drumbeat. Conceived in the days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Drumbeat was a long-range assault on Allied shipping in American coastal waters. German planners believed, correctly as it turned out, that the United States would be unprepared for a direct attack. Originally intending to send 12 submarines, only five could be mustered, and they pushed the limits of their operational range by striking the US coast.

The gamble paid off. When the submarines arrived off American shores in mid-January, they found a country that had made few preparations for war. Most merchant ships traveled without escorts, lights remained ablaze in cities and towns along the shore, and there were few of the bombers and destroyers that harangued them in European waters. There were so many easy targets, commanders called this “The Second Happy Time” (the first was in 1940 after the fall of France, when Britain was alone to defend its shipping).

U-123‘s first target was New York. Because the operation was so hastily arranged, the commanders were given spotty intelligence. For navigation, Hardegen was issued a large-scale chart of the eastern seaboard from 1870, a simple tourist map, and a guide to the 1939 World’s Fair (this last piece would prove the most useful, as it included a detailed map of New York Harbor). They arrived off the coast of New York on January 14, 1942, and though they nearly ran aground off the Rockaways, they managed to negotiate the area safely, thanks in part to the lights of Coney Island and headlights from cars driving along the shore. That night U-123 sank the tanker Coimbra just outside the harbor, aided by the silhouette created by the bright shore lights. Combined with the sinking of the tanker Norness off Montauk the night before, it was enough to stir a major panic. The sub then departed southward for targets off Cape Hatteras (for more on Hardegen’s exploits, pick up Michael Gannon’s excellent book Operation Drumbeat).

Hardegen’s first foray to America was a success, sinking eight ships during the seven-week patrol, and killing 250 seamen and passengers. But it was events during his second patrol that would leave a lasting impression on the New York landscape.

After departing their base in Lorient, France on March 2, 1942, U-123 again made the long and treacherous journey to America’s shores. On March 22, approximately 425 miles northeast of Bermuda, the sub encountered an American tanker, SS Muskogee. After stalking the ship for two hours to get a good firing angle, U-123 launched a single torpedo, which struck Muskogee amidships, sinking her in just 16 minutes.

The submarine then surfaced and found seven men huddled on a raft, and U-123 approached. Hardegen interviewed them about their ship – it was a 7,034-ton tanker carrying oil from Venezuela to Halifax – and then set them adrift in heavy seas with a few supplies and information about their position. In the war’s early days, German submarines would take survivors aboard, but they were westbound at the very beginning of their patrol, far from their bases and with no room for seven more bodies. During this encounter, the German war correspondent aboard U-123, Rudolph Meisinger, snapped several photos of the sinking ship and the survivors.

None of these men, or any of 34 crewmembers of the Muskogee, were ever seen again.

Rediscovering SS Muskogee

These photographs have survived, but their re-discovery came through several meandering paths.

Perhaps the most important figure in reconstructing the story of the Muskogee is George Betts, son of the ship’s master, William Wright Betts. When the ship was lost with all hands, American sources had little information about its fate. George, who was a teenager at the time of his father’s death, began researching the story later in life, and he eventually got ahold of U-123‘s logs through the National Archives.

Following his discovery that the Muskogee had been sunk by a torpedo, he then learned that Hardegen was still alive, and wrote him a letter. The two corresponded for years, and they eventually met in 1987 in Canada. Hardegen shared what he remembered, and he gave Betts some of Meisinger’s photographs, which he had kept.

Despite, the fact that Hardegen was directly responsible for his father’s death, Betts held no grudges. Betts’ research, and his encounter with Hardegen, was featured in a 1989 episode of Unsolved Mysteries, during which Betts said, “I had no animosity toward him, that’s the way I felt. I felt he was one World War II veteran that was on one side, and one World War II veteran that was on the other side. And in our cases, we were two of the lucky ones that survived the battles.”

How Escobar encountered the photo is an even more bizarre tale, involving someone completely unrelated to the Muskogee. George Duffy was a merchant seaman aboard the cargo ship MS American Leader when it was sunk by the German commerce raider Michel in the South Atlantic on September 10, 1942. 47 survivors were picked up by the German ship, and then transferred to another German vessel, the tanker Uckermark. It was there that Duffy found a copy of the weekly newspaper Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. In it he saw a full-page feature about the sinking of an unidentified American ship, including a photo of Hardegen, and of the seven men on a raft. He tore out the page and kept it.

Duffy and his shipmates were eventually transferred to Japanese custody, and he spent the next three years in labor camps in Java, Sumatra, and Singapore. Throughout this ordeal, he managed to save this newspaper clipping. When he returned to the US, he continued working as a seafarer, and he made attempts to identify the men in the photo, but it took more than 30 years before he realized that he had a photo of the Muskogee. It was this well-traveled copy that was eventually seen by Escobar and inspired her sculpture.

This is Duffy’s well-worn copy that was reprinted in the 1983 edition of Arthur R. Moore’s book A Careless Word … A Needless Sinking.

Tracking down a photograph

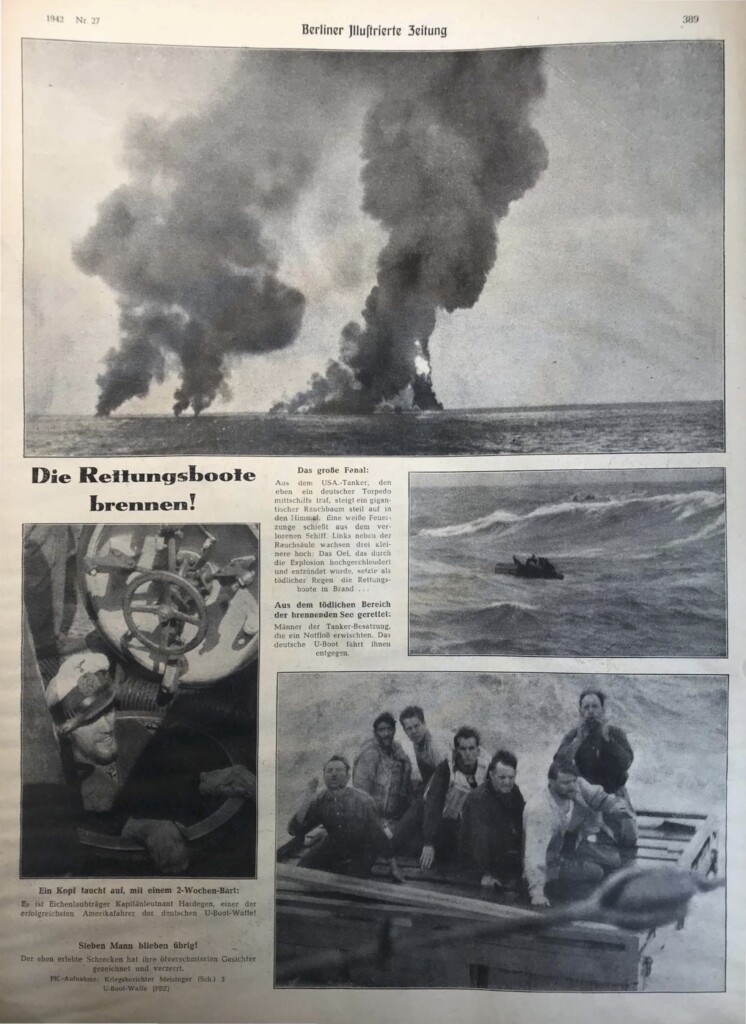

After learning the provenance of this photograph, we decided to track down a copy. For such an iconic image, no decent copies of it appear to exist online, as most are likely taken from republished newspaper clippings, and there is a great deal of conflicting information about the incident. Luckily, we were able to find copies of Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung at Manhattan’s Center for Jewish History. Based on the timeline of events – U-123 returned from its second patrol on May 2, and Duffy was transferred to the Uckermark on October 7 – we narrowed our search to these five months, and found the issue with the original published photo: July 9, 1942. Here is the full page:

And a translation of the German captions:

The lifeboats burn!

The big beacon:

From the US tanker, which was just hit by a German torpedo amidships, rises a gigantic smoke tree steeply in the sky. A white tongue of fire shoots from the lost ship. Three smaller ones grow to the left of the high smoke column: The oil that passes through the explosion was thrown up and ignited as deadly fire rained on the lifeboats.

Rescued from the deadly area of the burning sea:

Men of the tanker crew, who got caught in an emergency raft. The German submarine is driving towards them.

A head emerges, with a 2-week beard:

It’s decorated Captain Lieutenant Hardegen, one of the most successful America drivers of the German submarine force!

Seven men were left!

The newly experienced horror has drawn and distorted their oil-smeared faces.

PK recording; War Reporter Meisinger (Sch.) 3

Submarine Force

While the two photos on the lower right are clearly of the same incident, it is possible that the top photo is not. In all of Hardegen’s accounts of the sinking, both in his official log and in his conversations with Betts, he noted that there there was no huge explosion, and the ship did not burn. Since the attack was made while submerged, they also could not have photographed the initial explosion. In fact, the torpedo impact was so muffled, Hardegen thought that he had missed. But the shot was right on target, striking the engine room, destroying the bridge, and giving the crew no time to escape to the lifeboats. It’s likely that William Betts was killed instantly.

Hardegen was a celebrated war hero, as this propaganda makes clear. He even had a book published in 1943, mostly containing propaganda photos of his time at sea, titled Auf Gefechtsstationen! U-Boot im Einsatz gegen England und Amerika (To the Battle Stations! U-Boats In Action Against England and America). The photo below shows U-123 returning to Lorient after Hardegen’s second American patrol. The white pennants represent the tonnage of ships sunk; Muskogee is the on the left side, fourth from the bottom, marked “7,034.”

But the survivors of the Muskogee are depicted as pitiable, barely escaping an inferno, smeared with oil, and desperately seeking help. While Hardegen remains a well-known figure, some of the men in the photo are still unidentified. Four of their names are known – Vincent V. Baker, Anthony Sousa, Nathaniel Foster, and Morgan Finucane – but as the years pass by, and as fewer of their friends and family are still living, it seems unlikely that the names of the remaining three will ever be known. You can see a full list of the ship’s complement here.

With Hardegen’s passing, the last living link to the saga of the Muskogee, and to this iconic photograph, is gone. George Betts has since passed, though his treasure trove of research is now held at the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia. George Duffy died in 2013, but he has left behind a memoir, and he recorded an oral history interview with the Seamen’s Church Institute. And Marisol Escobar died in 2016, but she has left us a lasting tribute to the sacrifice of these brave men.