While many children will be gorging themselves on chocolate Easter bunnies and eggs this morning, these treats were absent from most baskets during World War II.

On December 5, 1942, the War Production Board, which supervised wartime industry, issued Conservation Order M-145, banning the manufacture of chocolate novelties, including “products manufactured in a special shape commemorating, symbolizing, or representing any holiday, event, person, animal or object.” The board proclaimed that, “American children will contribute to the war program by sacrificing chocolate Santa Clauses, St. Valentine’s hearts, Easter bunnies and eggs and other chocolate novelties.”

The ban went into effect on December 15, so it had little impact on Christmas 1942, and there were even enough stockpiles to cover Easter 1943 (though Japan was a major supplier of Easter baskets to the American market, so domestic supply had to be found). But within a few months, supplies ran out, and manufacturers and retailers had to come up with substitutes. For Easter 1944 and 1945, instead of chocolate bunnies, children received bunny-shaped pieces of wax, soap, or wood, and plush rabbit dolls began to appear. They bore their requisite eggs, but these were usually solid lumps of caramel instead of chocolate. Or if you were really unlucky, they might just be radishes.

The reasoning behind this strict rationing was twofold. First, the government wanted to promote a sense of shared sacrifice, and this was a way for children to feel that they were giving something up for the war effort. The board wrote:

“By giving up such items, the children will provide additional breakfast cocoa and chocolate bars for their soldier brothers and sisters who are fighting the war, for their fathers and mothers, some of whom are working in war plants, and for themselves.”

Second, the two principal ingredients – cocoa and sugar – were imported, so what little supply there was had to be used in the war effort. Even before the ban, chocolate was becoming scarce, as German U-boats in the Atlantic and Japanese conquests in Southeast Asia were choking off supply to the US.

As a product with a global supply chain, the absence of chocolate on store shelves illustrated the scale of the war; as the New York Times wrote in February 1943, “The candy map is the map of the world. … When the U-boats waylaid the sugar and spice and all things nice that go into candy, they brought the war to everybody in America.” Also contributing to the shortage was scarce labor, as many skilled confectionary workers (especially women) opted for war production jobs that also required tactile dexterity, assembling fuses and firearms instead of bonbons and bars.

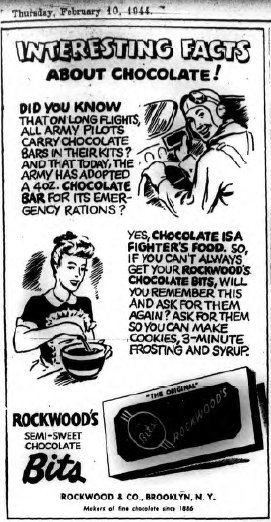

The nation’s candy factories were hardly idle, however. Boringly-shaped chocolate bars could still be made for consumers, and manufacturers large and small snapped up military contracts. Chocolate was seen as an essential item for the military, not only for morale boosting, but because it was calorie-rich and a natural stimulant. It did have some major drawbacks, in that it easily spoiled and had a low melting point, turning most bars into a gooey mess in the jungles of the Pacific or the deserts of North Africa.

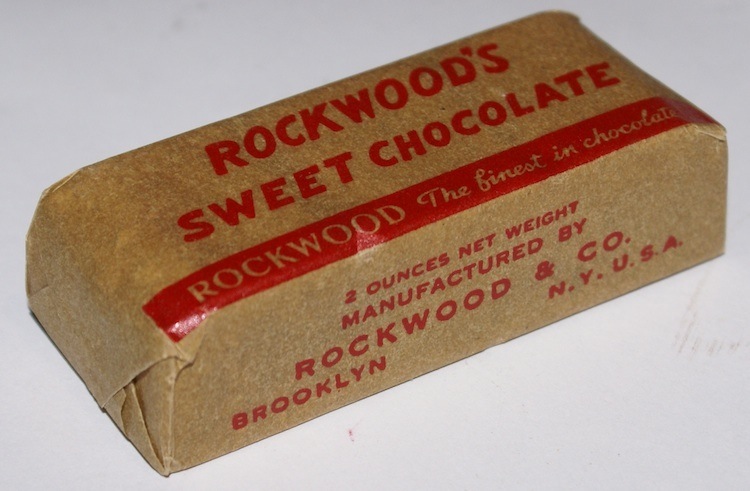

In 1937, the Army Quartermaster Corps began development of a new chocolate-based emergency ration that could survive in these unforgiving environments. They gave manufacturers strict specifications that the 4-ounce bar had to be high in calories and protein, not melt in high heat and humidity, and not taste too good – “a little better than a boiled potato” – to discourage snacking by peckish soldiers. Hershey’s ultimately developed the formula for the D Ration, which packed 600 calories and could remain solid at up to 120 degrees.

If you want to see what one looks like, one of our favorite YouTube channels, Steve1989MREInfo, “unboxes” and eats military rations from around the world, no matter how old. As he reports, the original 4-ounce D Ration was tough to eat and not very popular with the troops, so the formulation was changed slightly in 1943 to make it sweeter (pictured above).

Hershey’s was not the only manufacturer of this unpalatable chocolate. Among others, Brooklyn’s Rockwood & Co, located on Park Avenue and Washington Ave, a stone’s throw from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was also a major supplier. But Rockwood contributed to the war effort in other ways too.

The company’s advertisements touted that military pilots carried their D Rations for long flights, and it’s likely that Navy Lt. Wallace T. Jones, III, son of Rockwood’s president, had one with him on March 5, 1943. That was when he took off from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal in a B-24 Liberator bomber to attack Japanese ships around Bougainville. He and his 11 crew mates never returned from that mission. The exact circumstances of their downing are unknown, and the wreckage of their aircraft was never located.

One would hope that with the end of the war, everything would return to normal, and potato-tasting chocolate bricks would give way to delicate and delicious confections of simpler times. Unfortunately, because chocolate has such a long and complex supply chain, starting it up again after the war was difficult. Most cocoa came from British and French colonial possessions in West Africa, where the plantation economies had collapsed during the war. Easter 1946 was another lean year, and it was not until early 1947 that reliable supply was again available in the US.

So remember as you tuck into that chocolate Easter bunny – “The candy map is the map of the world,” and that map can be disrupted.