Operation Neptune, the seaborne component of the Normandy invasion, required nearly 6,500 vessels to deliver the vast Allied armies and their supplies and equipment onto the continental beaches. This didn’t just include warships and landing craft, but also more mundane vessels, like barges.

Allied planners scoured the British Isles for craft of any kind to use in the invasion, and they encountered a major shortage of large barges, capable of carrying 1,000 tons or more, and with a draft of less than six feet. Enough simply could not be found or built. Barges of this size were too large to load onto the decks of even the largest transports, and too fragile to tow across the stormy North Atlantic. So in February 1944, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower sent an urgent message to Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall asking for a solution.

The solution was found right here in New York, thanks to the somewhat idiosyncratic way we moved (and still move) freight. Every day, New York Harbor was crisscrossed by car floats, specialized barges with railroad tracks on them used to moving railcars. These car floats were necessary, since New York City lacks any freight rail crossing of the harbor or the Hudson River (in World War II, the river’s southernmost freight rail crossing was at Poughkeepsie, 75 miles away; today it’s at Selkirk, 150 miles upriver). But these barges were especially strong, capable of withstanding the battering of an ocean crossing, and of carrying more fragile wooden barges on their decks.

Thus, the “pickabacks” were born. Car floats were pulled from rail service, and smaller composite barges were brought up from the Gulf Coast to bind the two together. The preparation work was two-fold: first, outfit the car floats and tugboats for ocean towing. New, stronger cleats and hawsers were installed, and some were reinforced with new timbers and even concrete. More than 100,000 feet of rope, cable, and chain was procured. This work was done at several different yards, including at the Brooklyn Army Terminal’s Marine Repair Shop, as the New York Port of Embarkation was principally responsible for the operation. The venerable Moran Towing was also brought on as advisors.

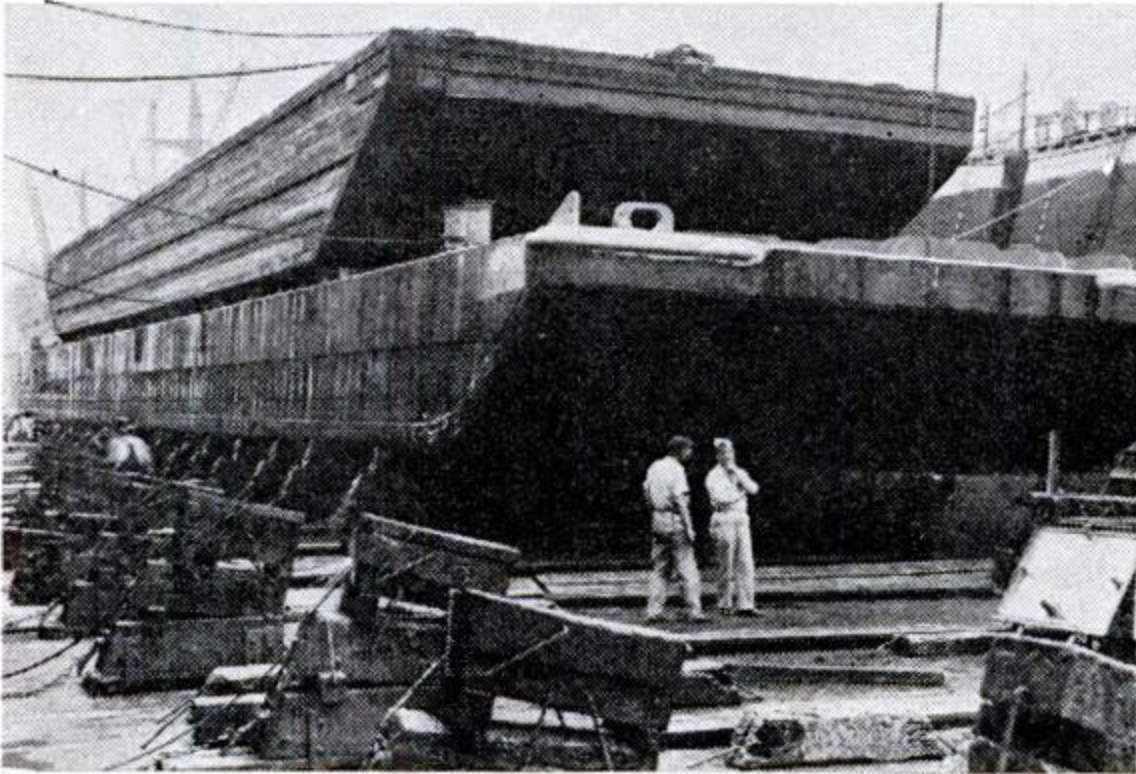

Second, they had to load the composite barges onto the car float decks decks. To do this, dry docks at six shipyards around the harbor were used. The car floats were intentionally sunk in these dry docks by cutting holes in their bottoms. Then, the composite barges were floated in and the dry docks pumped out, allowing the smaller barges to settle on top of the car floats. The holes were then patched up, and the loaded “pickabacks” were floated out.

Then came the really hard part: getting them across the Atlantic. The barges left in three convoys, the first leaving in April 1944, just two months after the operation began, and arriving in time for the invasion after a 28-day crossing. The second left in August, making it in 21 days, while the third was the most challenging, leaving in September and taking 32 to reach England, surviving a hurricane when just two days from landing. Many of the barges were lost en route, with one convoy losing 10 or its 14 barges, and at least two sailors lost their lives.

It was a costly and difficult operation, but the “pickabacks” were necessary tools for every step of the invasion. On D-Day +1, these barges were used to deliver large ammunition stocks to the beachheads. As the operation progressed and artificial harbors were built, some barges became breakwaters. And when Allied forces finally captured an equipped port, some even became car floats again, shuttling trains between Cardiff and Cherbourg.