This summer marks the 70th anniversary of the tragic events of Port Chicago, California, the worst home front disaster of World War II. 320 people were killed, most of them US Navy sailors, in an explosion at a naval munitions loading station, but it was more than just a tragic accident – the events leading up to and following the explosion exposed the appalling racial discrimination and mistreatment faced by African-American sailors during the war.

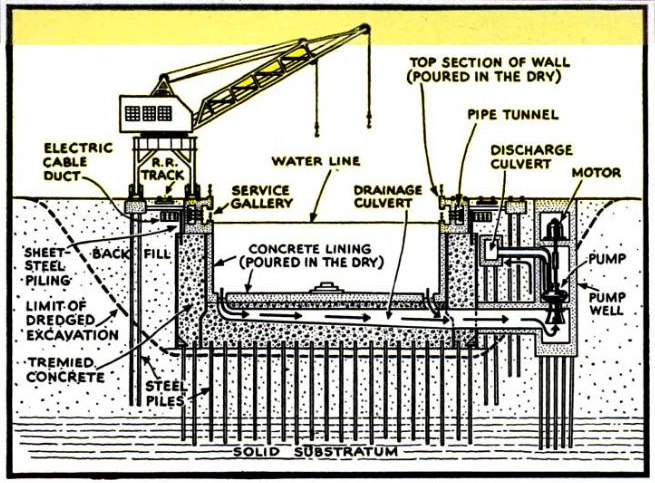

Located on central California’s Suisun Bay, Port Chicago was one of the largest and busiest weapons stations in the country, loading explosives onto ships bound for the Pacific Theater. All of the enlisted sailors carrying out these dangerous operations were African-American; all of their commanding officers were white. While many of these men had received training to pursue a naval rating, or a specific skill, they, like most of their black counterparts across the Navy, were employed only for manual labor. And the conditions at the port were incredibly dangerous. Commanders utilized “speed contests” to push the men to load more quickly, and almost none of the men had received specific instructions in ammunition loading or proper safety training.

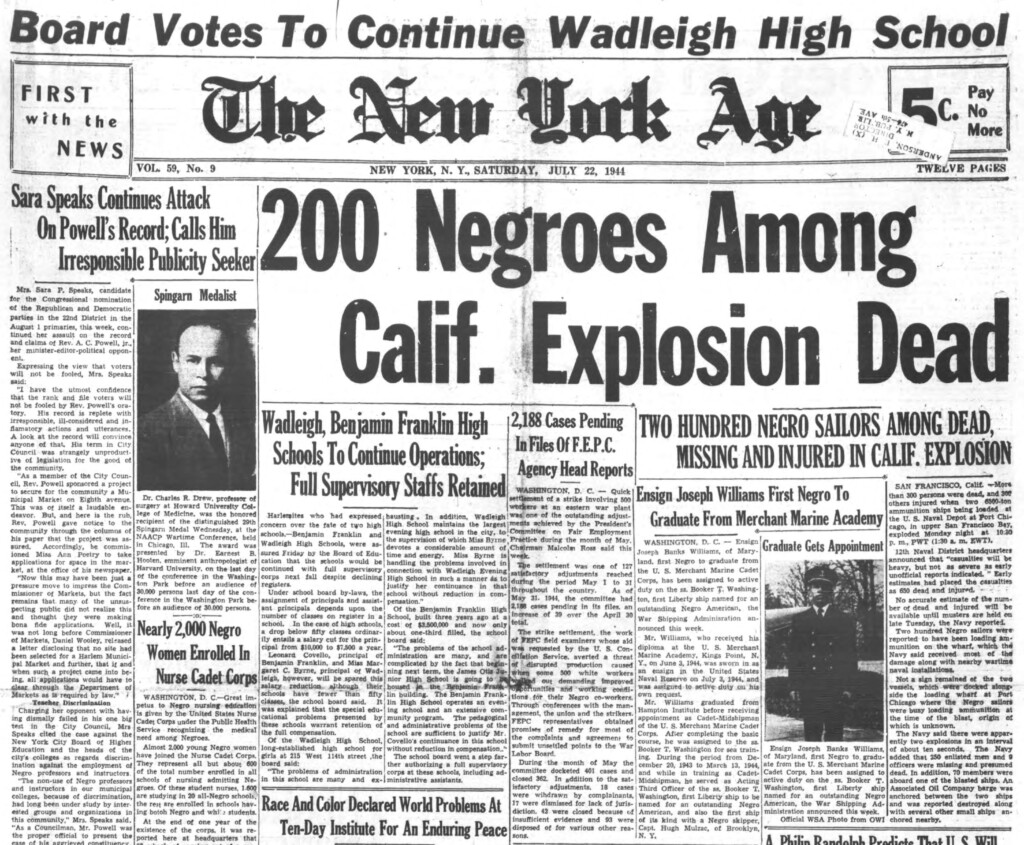

Then, at 10:18pm on July 17, 1944, an explosion rocked the Liberty Ship E.A. Bryan, destroying it and the neighboring ship, Quinault Victory. At the time, several different types of munitions were being loaded into three holds of the Bryan from neighboring train cars. One such operation was moving live incendiary bombs into the ship’s no. 1 hold by means of its shipboard crane, which was known to have a malfunctioning winch. However, the exact cause of the accident was never determined, as everyone who witnessed it, as well as the entire ship, were essentially vaporized. The explosion killed 320 men and wounded 390 – 202 of the men killed were African-American, as were 233 of the wounded.

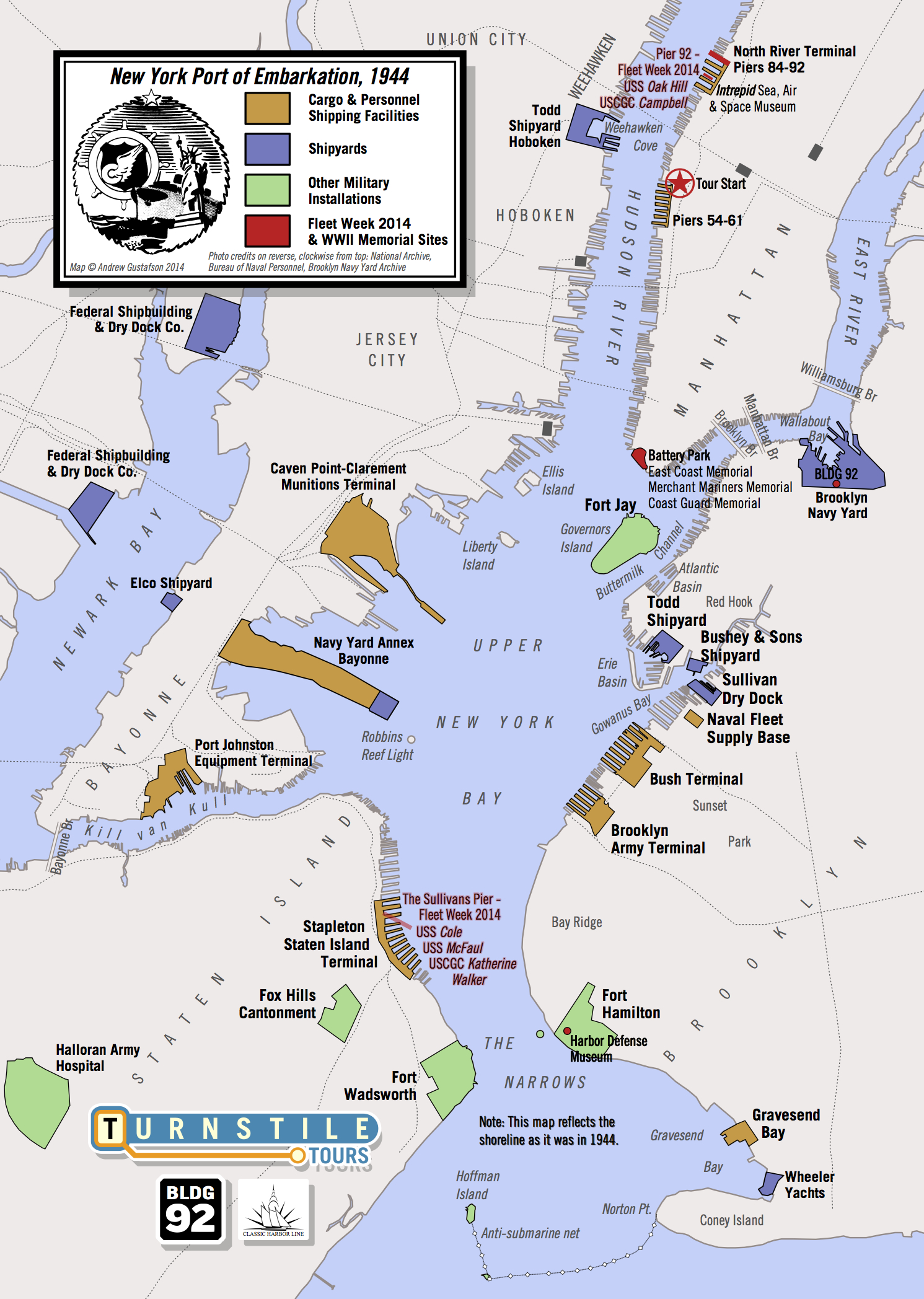

During the war, America’s ports were choked with ships moving high explosives to fronts across the globe, and a disaster like this could have taken place anywhere – luckily, the Navy had chosen a thinly-populated corner of California for this operation. New York Harbor, being the largest embarkation point of troops and supplies in the war, had its own share of wartime accidents, some of which were shockingly close to being full-blown catastrophes. The Army’s largest ammunition loading station was located at Caven Point in Jersey City. It moved more than 2.7 million tons of explosives during the war out of a finger pier located less than two miles from Manhattan. On April 24, 1943, the entire complex almost went up in smoke when the cargo ship El Estero caught fire. Carrying 1,365 tons of munitions, an explosion of that magnitude would have rocked the entire city. Thanks to the efforts of the ship’s crew, the US Coast Guard, and the fire departments of Jersey City and New York City (including the fireboat John J. Harvey), they managed to tow the ship away from munitions on the Caven Point pier and swamp her in shallow waters off Bayonne, extinguishing the fires and stopping the threat of explosion. Though some of the heroics during the El Estero incident came to public light, it was not until August 1945 that the full scale of the Caven Point facility was revealed to New Yorkers, and they learned there was a literal powder keg in their backyard.

At Port Chicago, however, disaster was not averted, and it exposed the racial powder keg the Navy had tried to keep bottled up. You can read a complete findings of the court inquiry into the disaster, which is, essentially, a whitewash, placing the blame for the explosion squarely on the enlisted men. In their “Finding of Facts,” they state:

“These enlisted personnel were unreliable, emotional, lacked capacity to understand or remember orders or instructions, were particularly susceptible to mass psychology and moods, lacked mechanical aptitude, were suspicious of strange officers, disliked receiving orders of any kind, particularly from white officers or petty officers, and were inclined to look for and make an issue of discrimination. For the most part, they were quite young and of limited education. … Because of the level of intelligence and education of the enlisted personnel, it was impracticable to train them by any method other than by actual demonstration.”

Essentially, they justified the lack of safety training by arguing that the enlisted men would not have understood it anyway. The court concluded that “the details of loading procedure at Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, were as safe, and in most cases safer, than those in use at many other points,” and that, “the officers at Port Chicago have realized for a long time the necessity for great effort on their part because of the poor quality of the personnel with which they had to work.”

Loading operations at the base were stopped for a time as the cleanup and inquiry into the causes were conducted. But on August 8, just three weeks after the disaster, men were put back to work loading at the same facility, with few changes to the conditions, leadership, or safety measures. Many of the enlisted men who witnessed the explosion had asked for 30-day “survivor’s leave,” customarily given to sailors who experienced a traumatic event; the leave was denied to all the African-American sailors, but granted to all of their white commanding officers. When orders were given to recommence loading, 258 sailors refused; all were arrested. After being pressured by Naval officers and threatened with execution, all but 50 of these sailors returned to work.

Those men became known as the “Port Chicago 50.” After a six-week trial, all were found guilty of mutiny and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor. Though the NAACP and future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall mounted an appeal campaign for the sailors, their convictions were reaffirmed in June 1945. It was only the cessation of hostilities that convinced the Navy that the convictions had lost their usefulness as “messages” to other “mutineers,” and the sentences were reduced to one year.

It was not just the so-called mutineers who were roughly treated, but also those who were killed. The Navy had initially proposed compensation of $5,000 to the families of each person killed; that number was reduced to $3,000 under pressure from Mississippi Congressman John Rankin, who felt that it was too high a price to pay for black lives.

Port Chicago was not a unique case, and the Navy’s record of race relations was perhaps the worst of all the armed services. Prior to the war, all African-American sailors were limited to serving as steward’s mates – they served on ships with white officers and crews as cooks and cleaners, and were denied the same ratings as other Navy branches. From 1919 until 1932, the Navy completely barred the enlistment of blacks, hoping to fill the entire steward corps instead with Filipinos. When the ban was lifted, cooking and cleaning were all that were open to them, but by 1941, the need for men in the expanding Navy eventually convinced them to open up other branches and ratings to African-Americans.

Even after this change, postings for African-Americans were heavily concentrated in shore duties like the construction battalions (“Seabees”), the commissary branch, stevedoring, and ammunition handling, and their shipboard service was mostly limited to harbor craft or commissary duties aboard warships. As the war progressed, more and more ratings were opened up, including machinists, radiomen, shipfitters, gunner’s mates, and hospital corpsmen (one such recipient of this last rating was Robert Hammond, who served at the Brooklyn Naval Hospital and contributed an oral history to the Brooklyn Historical Society archive).

Still, the Navy did not commission any African-American officers until 1944 (the “Golden Thirteen”), and it was not until 1949 that an African-American graduated from the US Naval Academy (Wesley Brown). By comparison, the US Army achieved those milestones in 1865 and 1877, respectively. Only two Navy ships in World War II – the destroyer escort USS Mason and the submarine chaser PC-1264 (which happened to built in the Bronx, commissioned in Manhattan, and currently sits in a ship graveyard off the west coast of Staten Island) – were fully crewed, and not just cleaned and fed, by African-Americans.

The Port Chicago Disaster is largely forgotten, in part because it upsets the narrative of the United States in World War II as a harmonious society pulling together in a time of war. While we celebrate African-American figures like the Tuskegee Airmen and Pearl Harbor hero Dorie Miller, we often forget that the military (as well as most of American society) was completely and unapologetically segregated. The country experienced major race riots in places like Detroit and New York City (both sparked by altercations with servicemen, both fueled by racial conflicts over over wartime housing and jobs), and in many cases, the retrenchment of Jim Crow. But the war also opened up new opportunities for African-American servicemen and workers, and they took advantage of them, demonstrating their heroism and skill, and paved the way for the desegregation of the military and the Civil Rights Movement. Roughly 125,000 African-Americans served in the Navy, and more than one million served across the armed forces during World War II. These men and women – like the sailors of Port Chicago – demanded that their sacrifice be rewarded with full and equal rights, and they set a sterling example for the generations of civil rights campaigners that followed them.