Since we began working at the Brooklyn Navy Yard nearly ten years ago, the Yard has become a huge part of our lives and our identity, both as a company and as individuals. We see connections to its past and present nearly everywhere we go, and we are learning new things about it every day.

We are always looking for new ways to bring the stories of the Yard to life for the public. It has been nearly 40 years since a ship was launched from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and more than 50 since a US Navy ship was built there, so shipbuilding can seem like a distant memory. We have found that actually seeing the products of the Yard’s workers is not only a great inspiration, it also helps us better understand the nature of the work that went into them. It’s one thing to talk about welders, shipfitters, caulkers, and riggers building a 45,000-ton battleship; it’s another entirely to actually see the sum of that labor and how it all fit together. Unfortunately, only a small number of Brooklyn-built ships still exist, but we have been lucky enough to visit a few of them over the years.

USS Iowa, Los Angeles, CA

Our first visit to the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built ship was in 2013. With a pair of airline vouchers from getting bumped from a flight, we went looking for a destination we could fly to for under $300. Some friends had recently move to Los Angeles, so we decided to take a week off and relax on the beach, camp in Joshua Tree, and see some sights. We ended up spending two entire days in San Pedro.

Iowa is one of the most celebrated ships of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Built during World War II as the lead ship in a new class of battleships, she earned nine battle stars, and even carried President Roosevelt to an allied conference in 1943. Carrying the biggest guns in the Navy, Iowa was recommissioned for the Korean War and again in the 1980’s, along with her sister ships New Jersey, Missouri, and Wisconsin. An accidental explosion during a gunnery exercise in 1989 killed 47 sailors and ended Iowa‘s career as a fighting ship. After spending 21 years bouncing around reserve fleets, the ship was brought to San Pedro on Los Angeles Harbor in 2011 and opened to the public as a museum on July 4, 2012.

Before our trip, we got in touch with the curator, Dave Way, and he rolled out the red carpet for us. We clamored all over the ship, visiting their exhibits, engineering spaces, and archives. We really got a sense of the monumental labor that went into transforming a 70-year-old, 45,000-ton ship into a sustainable, engaging, and safe attraction for the public. Read more about our visit here.

USS Saratoga, Newport, RI

Cindy and I visited Newport, Rhode Island for our honeymoon* in April 2014 – yes, we had pretty much an entirely Navy-themed honeymoon (and yes, Cindy and I are married). We visited the Naval War College Museum, stood in awe in the same classroom where Capt. Alfred Thayer Mahan gave his groundbreaking lecture series “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History,” and we visited the graves of a vaunted naval family.

Admittedly, this was a ship we only saw from a distance, and did not get to go aboard. A fixture of the waterfront in Newport for 16 years had been the hulk of the USS Saratoga. Built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1956, the supercarrier spent 38 years on active duty. After being decommissioned in 1994, the carrier was towed to Newport in 1998, with the hope that it would become a museum ship in that city. Campaigns were launched, money was raised, plans were laid, but in 2009, the Navy removed it from the “donation hold” list and marked it for disposal. We saw her just four months before she would be towed out to sea and down to Brownsville, Texas to be cut up for scrap.

With the scrapping of the Independence last year and the Constellation and Saratoga in 2014, all of the Brooklyn-built carriers are gone. There is hope for Newport, however, and for preserving the history of the conventionally-powered supercarrier; the city is making plans to bring the John F. Kennedy to town as a museum (though they have hit some snags recently).

[* Editor’s note: Cindy objects to me calling this our honeymoon. Yes, we went to Newport immediately after our wedding, but we were only there for two days, and we did all of this work-related stuff. It also rained the entire time.]

USS Ohio, Greenport, NY

While we only saw Saratoga from afar, we actually failed in our quest to see the remains of the first ship built at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Laid down in 1817 and launched three years later, Ohio spent 55 years alternating between active duty, reserve, and receiving ship (a type of floating barracks). In 1883, the ship was sold to a private buyer, and the following year it was brought to Greenport, on the north fork of Long Island, where it was stripped of its copper, brass, and iron, and the remains were burned and sunk in the harbor.

In the 1973, divers rediscovered this wreck, and it became a popular diving site. It sits in about 20 feet of water just off an area called Fanning Point, where there is a small town beach. Last summer, we happened to be vacationing in Greenport, so we decided to take a little swim to see what we could find.

I should say that neither Cindy nor myself are scuba divers. We have no experience with diving or underwater archeology of any kind. So we bought some snorkels from a local toy store, consulted some information from an internet scuba forum, and headed out the beach. We did not expect to find anything – not only is 20 feet way too deep for inexperienced free divers, the water is incredibly murky, and the wreck has been largely picked clean over the decades. But we figured we were in roughly the correct area, so we made few dozen dives as deep as we could and blindly ran our hands over the sandy bottom. Nothing. But a fun afternoon.

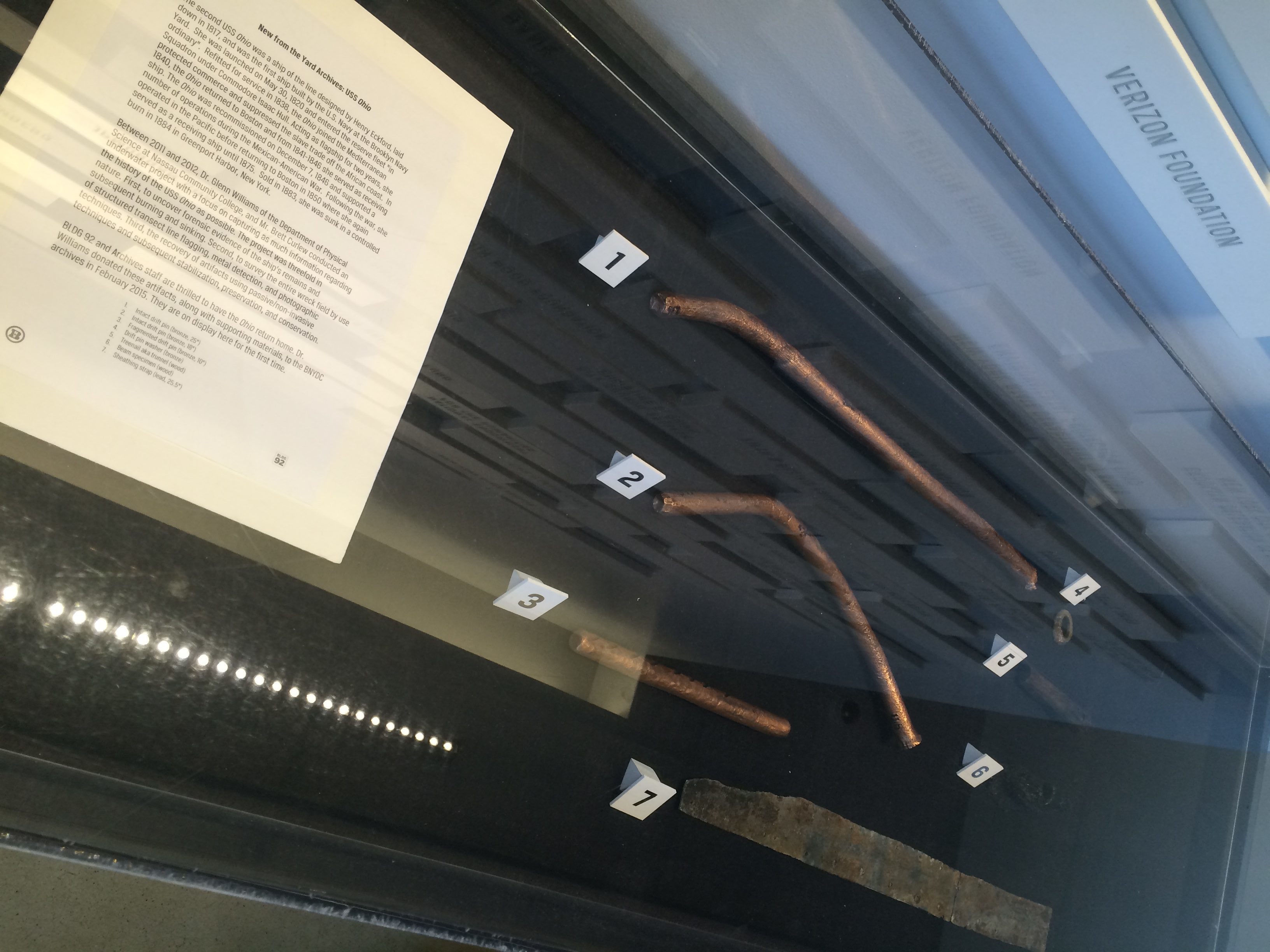

Luckily, people who actually know what they are doing have worked to document and preserve this wreck. In 2011 and 2012, Dr. Glenn Williams of Nassau Community College and Brett Curlew conducted a research study to survey the site and recover artifacts from it. Many of these items, including metal components and pieces of timber, were donated to the Brooklyn Navy Yard Archive, and they were on view at BLDG 92 in 2015-16. You can also see the ship’s anchor and figurehead of the Ohio on display in Stony Brook, Long Island.

USS Arizona, Pearl Harbor, HI

Hawaii has always been high on our list of places to visit. We went there last month, in part for vacation, but the fact that we could also visit Pearl Harbor was an enormous draw for us as well. Within an hour of landing in Honolulu, we were at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center waiting to take the short boat ride out to the USS Arizona Memorial.

The Arizona holds an outsized place in the history of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Completed in 1916, it was the pride of the Navy at the time. Then-Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt even attended the keel laying. By 1941, it and most of the other battleships in the Pacific Fleet were aging, but still useful. When the Japanese attack came on December 7, eight Brooklyn Navy Yard-built ships lay at anchor, but only Arizona was sent to the bottom, thanks to a direct bomb hit to the forward magazine. With a loss of 1,177 of her crew, it was the largest loss of life aboard any US Navy ship in history, and an event that hit Brooklyn especially hard. More than 1,000 Yard workers volunteered to travel to Hawaii to help put the fleet back together.

Visiting Pearl Harbor entails more than just the Arizona Memorial. From the visitors center, there is access to the four main attractions: the memorial itself, the submarine USS Bowfin, the Pacific Aviation Museum, and the USS Missouri. If you are planning to visit, admission to the memorial is free, but you can book timed tickets up to two months in advance (with a small online service fee), and they almost always sell out. A limited number of tickets also go on sale every day at 7am (Hawaii Time) for the following day, or you get there early for walk-up tickets. The other three sites charge admission.

Prior to the visit to the actual memorial, which involves a short boat ride, the visitor center provides excellent contextual information, both in the two museum exhibits, “Road to War” and “Attack,” and in a 23-minute video introduction. The narrative is detailed and complex, connecting the root causes of the war to Japan’s conquest of China, and its desire to seize resources for that conquest from the Asian colonies of the Western powers. The video and exhibits also provide a near-minute-by-minute account of the attack itself, and they ways it impacted the lives of the military and civilians in Hawaii. One of the highlights of the exhibits are all of the touch models for people with visual impairments.

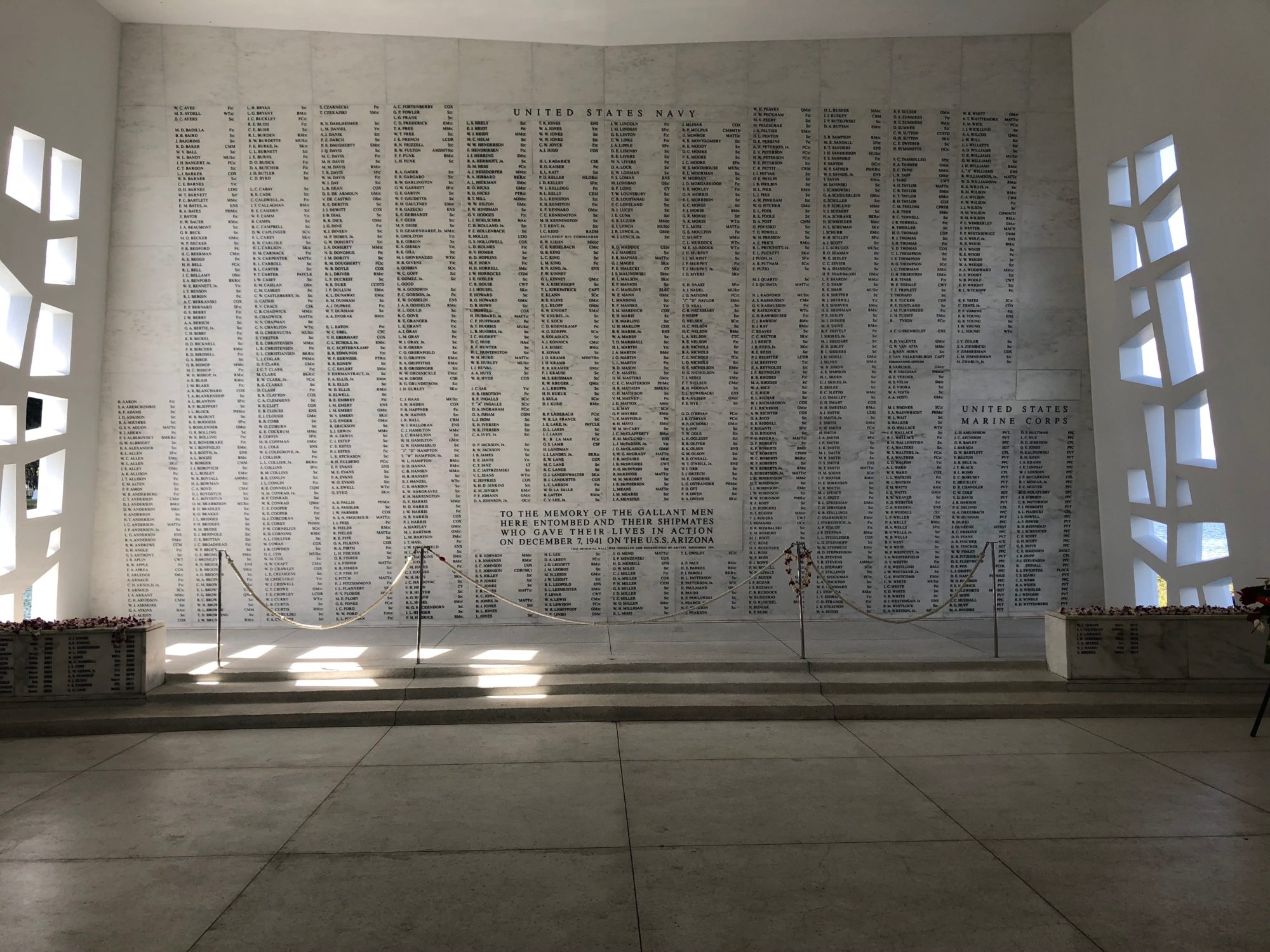

But the centerpiece of the experience is the memorial itself. The boat ride to Ford Island takes just a few minutes aboard a Navy launch, and offers views of the memorials as well as the active military base. The memorial is situated atop the hulk of the Arizona, where you can clearly see the ship’s outline and its gun turret barbettes poking above the water from the enclosure. But more than a rusted, leaking ship, you are looking at a grave, as the vast majority of those killed remained entombed in the ship. The sheer scale of the losses aboard this single vessel is driven home in the chapel-like space at the rear of the memorial, where the names of the dead are engraved on the wall. Be sure to look at the smaller engraved panels to the right and left of the main wall – these bear the names of the men who survived the attack, but have chosen to have their ashes returned to the wreck after they die, an honor that the Navy extends them. With just five survivors still with us, soon this memorial will also be complete.

Perhaps the most evocative part of our visit was just staring into the water, where you can see oil rising to the surface, a continuous trickle that produces swirling rainbows. Roughly 2–9 quarts of fuel oil leak from the hulk daily, from the estimated half-million gallons that remain trapped in the hull; this is referred to as the “tears of the Arizona.”

While looking out, I noticed something else – we could actually see four ships of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, or at least the memory of them. Along the edge of Ford Island are a series of concrete quays that mark the position of the ships on the morning of December 7, ghostly memorials to long-departed ships. Next to Arizona was the repair ship Vestal, built in 1909, and in front was the battleship Tennessee, built in 1919; both survived the attack, but are just memories today. Further down the row sits a very real and intact ship that came into being two-and-half years after the Arizona was destroyed.

USS Missouri, Pearl Harbor, HI

We often say that the Brooklyn Navy Yard represents the bookends of American involvement in World War II. The attack on Pearl Harbor and the sinking of the Arizona drew the country into the war, and it was concluded on September 2, 1945 on the deck of the USS Missouri, when Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender. We finally got to see those bookends right next to each other.

First, we want to thank the tremendous staff of Missouri for hosting us on our visit, especially director of visitor operations Frank Clay and curatorial assistant Meghan Rathbun. They were incredibly generous with their time and knowledge, and we learned so much not just about the ship, but the day-to-day operations of a battleship that has hosted over 8 million visitors in less than 20 years as a museum. Running a museum ship is really unlike any other cultural site. Ships are vast, intricate machines that also happen to be sitting in corrosive salt water. The battle for basic maintenance requires technical expertise and enormous human labor just to keep the sea at bay, in addition to requirements for hosting the public, developing programs, and building and maintaining an archive.

As an example, Meghan had previously worked for many years on another Iowa-class battleship, Wisconsin in Norfolk, Virginia, and her knowledge of these ships was so encyclopedic that she could tell the slight differences in the positions of doors, ladders, and equipment on what were supposed to be identical ships. She also took us to their archive, where they not only have to collect and preserve materials related to the ship’s history, they also have to hoard spare parts to keep the ship in working order, as no one has manufactured needed components in decades – another common problem for historic ships.

In addition to our time meeting with the staff, we also took a public tour of the ship, the “Heart of the Missouri Tour,” which took us into spaces off limits to the general admission public. Our tour guide, Joe Kiefer, was a US Navy vet, and he did an excellent job breaking down the operations of the ship, and the jobs of the individual sailors that kept it running. Climbing into the 16-inch gun turret was especially fascinating, as we could see the enormously complex machinery that loaded and fired these gargantuan, 2,700-pound shells.

But throughout the ship, the “ship art” – cartoons, maps, slogans, and signage painted by the crew – was one of the highlights. While many historic ships try to capture the most important moment in history – in this case, World War II – the Missouri is committed to portraying the full career of the ship, and their reference point for interpretation and preservation is not 1945, but 1991, when the ship completed its last mission: the 50th anniversary commemoration at Pearl Harbor. As a result, this ship art, which mostly dates from the 1980’s, plays an important role in evoking that moment in time.