The Brooklyn Navy Yard is 5,000 miles from Pearl Harbor, and though the reverberations of the events there on December 7, 1941 were felt across the globe, they hit especially hard on this small stretch of the Brooklyn waterfront.

Already 140 years old at the time, the Brooklyn Navy Yard had established itself as one of the most venerable shipbuilding and ship repair facilities in the Navy, and the Yard would be pushed to the limit during World War II, building, repairing, and servicing more than 5,000 vessels in just four years. Not only would ships be brought from across the world to be patched up and pushed back into the service at the Yard, but the Yard’s skilled craftsmen would be dispatched to other shipyards to help keep the fleet in fighting order.

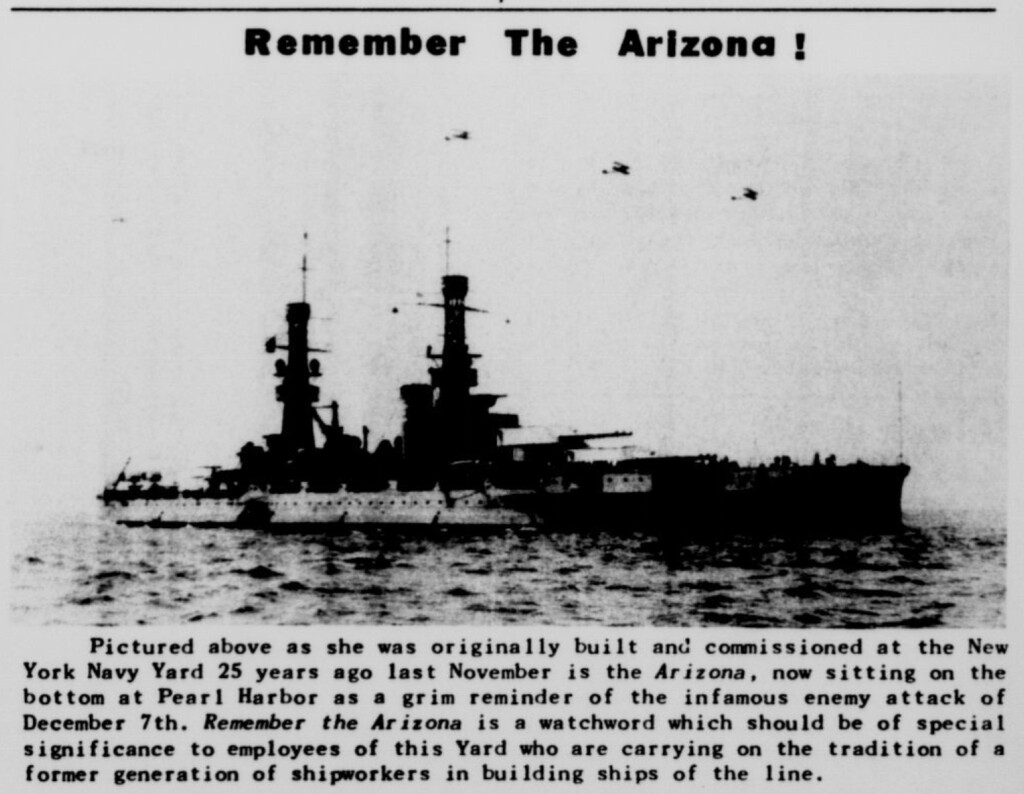

On the morning of December 7, eight Brooklyn Navy Yard-built ships sat in Pearl Harbor, as well as countless others that had been repaired and refit at the Yard at some point in their careers. The destroyers Hull and Dale were moored on the north end of the harbor; the heavy cruiser New Orleans and the light cruiser Honolulu sat in a berth near the harbor’s Southeast Loch; the heavy cruiser Helena was at the “1010 Pier”; and the USS Arizona was lined up on Battleship Row on the east side of Ford Island, with the repair ship Vestal alongside and the Tennessee in front of her (see map). Arizona was one of eight battleships assigned to Pearl Harbor. Completed in 1916, she was one of the many aging World War I-era battleships that formed the backbone of the Pacific Fleet at the outbreak of the war, though she was modernized in 1931 and boasted an impressive array of twelve 14-inch guns. But she would never fire a shot from these big guns in the war.

The attack commenced at 7:48am. Japanese aircraft operating from six aircraft carriers positioned northwest of Hawaii attacked an array of Army and Navy installations in two waves. Their objective was to destroy or disable as much of the American Pacific Fleet as possible – especially battleships, aircraft carriers, and aircraft – so that America could not interfere with Japanese military operations in the region. While the attack was a surprise, it was not completely unexpected, nor was it isolated. Japanese-American relations had deteriorated significantly over American economic sanctions, and war appeared imminent. But the attack on Pearl Harbor was just one prong of a coordinated offensive across the Pacific region; within 12 hours of the Pearl Harbor strike, Japanese forces attacked Thailand, British Malaya, Guam, Wake Island, Hong Kong, and the Philippines.

The toll of the attack was tremendous. 2,390 Americans lay dead, and 20% of the fleet lay sunken or burning. The greatest devastation was wrought on the decks of the Arizona. Struck by four bombs, it was the last one that pierced its forward ammunition magazine that did the real damage. A tremendous explosion rocked the ship, lifting its 30,000 tons of steel nearly out of the water. Within minutes, it had settled on the bottom of the harbor, and 1,177 of her 1,512 crewmen were dead. Word of the attack spread quickly, and the loss of the Arizona hit the Brooklyn Navy Yard especially hard. But it was not as if the Yard suddenly changed overnight on December 8. No, the Yard had already been preparing for war for years.

In 1938, the US Navy adopted a plan to expand shipyard facilities across the country, including in Brooklyn, and in 1940, the federal government passed the “Two-Ocean Navy Act,” calling for a huge expansion of the force. By mid-1941, the Brooklyn Navy Yard had taken over its former neighbor, the Wallabout wholesale food market, and began construction of new buildings and dry docks, nearly doubling in size. On the eve of the Pearl Harbor attack, there were 25,000 people working there, a four-fold increase in just three years. Within 18 months of the attack, all of the major expansion projects would be complete, and the Yard would be operating at full capacity, employing more than 72,000 workers.

Almost immediately after word of the attack reached New York City, Brooklyn Navy Yard workers did spring into action, volunteering for service in Pearl Harbor. More than 1,000 signed up, including 750 shipfitters (though the number of workers who ultimately traveled to Hawaii is not known). On January 9, 1942, a special ceremony was held at the Yard to send off the volunteers. Yard Commandant Rear Admiral Edward J. Marquart addressed the workers, as quoted in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Yard’s weekly newspaper The Shipworker:

You are doing just as much as the Navy and Marine Corps. You are doing just as much as the men rushing to recruiting stations. I would rather have you do what you are doing than shouldering a rifle. You are skilled workers and we need your skills. The whole United States is in back of you, just the same as the man in uniform, and like them you will find comfort in that which will compensate for the personal sacrifices you may be making.

The Shipworker also noted that Adm. Marquart had previously had under his command in the US Asiatic Fleet the minelayer Oglala, sunk at Pearl Harbor, and the gunboat Panay, which had been sunk by the Japanese in China in 1937 in what they claimed was a case of mistaken identity. In reference to these two ships, Marquart added, “When you get there remember this – with every blow of your pneumatic hammers, dig in two extra for me.”

The amount of work to be done at Pearl was immense. Four battleships lay at the bottom of the harbor, another run aground, and three more heavily damaged. Another nine major ships were damaged, the unarmed target ship Utah was sunk, and 188 Navy and Army aircraft were destroyed in the air and on the ground. Luckily, all three American carriers – Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga – were at sea during the attack, so the Japanese missed the real prizes, and they failed to severely damage the shipyard. These would prove to be critical mistakes.

The attack had come in two waves, but a third wave had been contemplated by the Japanese commanders. This was abandoned for a number of reasons, including worsening weather, dwindling fuel, and stiffening American resistance. The force was already at the edge of its operating range, and the commanders worried about safely returning their carriers to Japan intact. They had also not located the American carriers, and they feared counter-attack from land- or sea-based aircraft. The main targets of the third wave were meant to be fuel depots, maintenance facilities, and dry docks. Had this wave been successful, it would have severely hampered the ability of the Navy to operate anywhere in the central Pacific and greatly prolonged the time before America could launch any offensive action.

So the workers got to work. Of all the ships sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor, only two – the battleships Arizona and Oklahoma – did not return to service. By the end of the war, all those battleships and carriers thought to be so essential to the fleet in 1941 would be replaced by a new generation of ships that would tip the scales of the Pacific War, ships like the Brooklyn Navy Yard-built carriers Bennington and Bonhomme Richard and battleships North Carolina, Iowa and Missouri, the latter of which today sits nearby the wreck of the Arizona as a museum ship – the bookends of America’s war now united. With America’s industrial might, and the skill of our workforce, we could build and repair more ships than the enemy could ever sink. It was places like the Brooklyn Navy Yard and its workers that turned the attack on Pearl Harbor from a national calamity into a temporary setback.

Watch Andrew discuss the links between the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Pearl Harbor on News 4 New York:

[Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article stated that six Brooklyn Navy Yard-built vessels were present during the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941; in fact, there were eight. The earlier version failed to mention the battleship USS Tennessee (BB-43) and the light cruiser USS Honolulu (CL-48).]