After nearly 12 years of leading tours at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, one of the most difficult questions we get – and almost always from young people – is this: Were there slaves here?

This question is vexing not just because of the complex and painful subject matter, but also because the historical record is incomplete. The result is usually an imprecise and unsatisfying answer. In short, yes, enslaved people were an integral part of life at the Brooklyn Navy Yard for the 60 years leading up to the Civil War, just as they were across Brooklyn and New York City.

This is an effort to unpack that complexity and get somewhere closer to the historical truth of the matter.

Slavery in Kings County

In 1801, Kings County, New York, was a landscape of farm estates and small villages, with a total population of less than 6,000. The metropolis of New York City had more than ten times as many inhabitants, and the communities across the East River were its hinterland, providing food, timber, and other raw materials, but not much in the way of manufactured goods or labor for the city’s industries.

While New York City was becoming more cosmopolitan, Brooklyn clung to its Dutch roots, with nearly half the county’s population of Dutch heritage, despite the fact that Dutch rule had ended more than 130 years earlier. While the white population was largely homogeneous, more than one-quarter of the inhabitants were enslaved people of African descent, or 1,477 people, plus 322 free black people. Of all the counties in New York State, Kings County had the largest proportion of households that owned slaves, with nearly 60% ownership, far higher than in most southern states.

Though slavery in Brooklyn did not always resemble plantation slavery of the South, it was in many ways more ingrained into the culture and the economy. Most families owned small numbers – the county’s largest slaveholder in 1801 had 16 people enslaved – and owners and slaves lived in the same household. Families that did not own slaves themselves would often hire them from their neighbors. The few free blacks in the community had limited economic options other than farm work alongside their enslaved brethren. Advertisements offering rewards for runaways were a fixture of local newspapers. As Craig Steven Wilder puts it in his book A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn, “virtually all freeholders experienced mastery.”

The turn of the nineteenth century was a pivotal moment for the economy and culture of Brooklyn. Legally speaking, by 1799, slavery was on its way out in New York. A law passed that year granted freedom to anyone born after July 4, 1799, with the caveat that boys born to enslaved mothers would remain enslaved until the age of 28, while girls would remain so until age 25. This essentially set a clock for July 4, 1827 to end slavery in New York. Another law passed in 1817 also set this emancipation date for anyone born before July 4, 1799. While gradual manumission and the changing economic landscape did tamp down slavery across New York, it remained steadfast in Brooklyn. By 1820, there were still 879 enslaved people in Kings County, almost exactly equal to the free black population, while just 518 slaves remained in New York City, where there was a thriving free black community of over 10,000.

Another event would change the economic landscape of Brooklyn was the establishment of the New York Navy Yard on February 23, 1801. Purchased in the waning days of the Adams administration, the Navy acquired 40 acres on the western shore of the Wallabout Bay, a small, swampy bend in the East River. The land already had a small private shipyard, owned by John Jackson, which had only operated for three years, building a handful of commercial ships, and one for the Navy, the misbegotten 28-gun frigate USS Adams. Jackson, himself a slave owner, then made the transition that many did in Brooklyn, from provincial landlord to wealthy powerbroker. As the nascent village of Brooklyn grew, he moved into real estate, building homes for the growing population of Irish immigrants that flocked to the shipyard for work.

In short, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was established in the midst of a community where slavery was entrenched, widespread, and accepted. But in many ways, the Yard was like the city around it – as Brooklyn grew, the rural economy and the local need for slave labor dissipated; at the same time, the economy became more focused on industry and commerce, linking it closely to the production of commodities by enslaved labor in the South. Similarly, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was not a local enterprise, but a federal institution that drew resources and manpower from across the country. As the local representation of the most powerful military force in the nation, the Yard was subject to the deeply divisive, and often contradictory, policy decisions about how to deploy that force – to at times support, and at times to confront, the institution of slavery.

Slavery in the Navy

Very little is known about the prevalence of either enslaved or free people of African descent across the Navy, both in the service and as part of the civilian workforce. The Navy never kept track of the race of enlisted sailors, and in the civilian workforce, records are incomplete, and the federal government made only half-hearted efforts to curb or even track the use of slave labor. We do know that large numbers of black people served the Navy in the Revolutionary War, but in 1798, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert (who was instrumental in the creation of the Brooklyn Navy Yard) ordered that “no Negroes or Mullatoes are to be admitted.” By all accounts this prohibition was very weakly enforced, in part because Stoddert’s Navy faced huge manpower shortages. By the time of the War of 1812, sailors of African descent may have made up as much as 10% of the fighting force, and the ban was lifted in 1813.

Beyond the Navy, black people were not just common, but an indispensable part of the waterfront workforce in New York in the early nineteenth century. Seafaring was an attractive profession, as it provided escape from some of the exploitation and indignities that black people, free and enslaved, were subject to on shore. While becoming an officer or a shipowner were out of reach for nearly all, it provided a great deal of personal and economic autonomy. By 1825, an estimated 18% of all seamen in the port of New York were black.

While free blacks made positive, if unrecognized, contributions to the Navy, slavery was entrenched in the operations, logistics, and culture of the force. For one, many of the basic commodities that were required to build and maintain the fleet – live oak timber, hemp, and cotton – came almost entirely from southern producers utilizing slave labor. While Navy Yards would have manufactured much of their own rope and sails in-house or sourced them from local producers, an increasing number of slaves in the South were being employed in industrial operations. Plantation owners established textile mills and rope factories, and slave labor produced most of the nation’s turpentine; even iron and brass components may have been touched by the labor of enslaved people. As Robert Starobin describes in “The Economics of Industrial Slavery in the Old South,” “While some industries employed slave managers, others used highly skilled white technicians – imported from the North or Europe – to improve the quality and the competitiveness of industrial products.”

As for detailed information on the workforce of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the earliest extant records date to 1840, after the end of slavery in New York, and the records that do exist show no official employment of any black people, free or enslaved. In 1862, Commandant Hiram Paulding even went so far as to say, “There is not a colored person employed in the Navy-yard, nor has there been since the day I assumed the command, or before that time as far as I know.”

Slavery in Shipbuilding

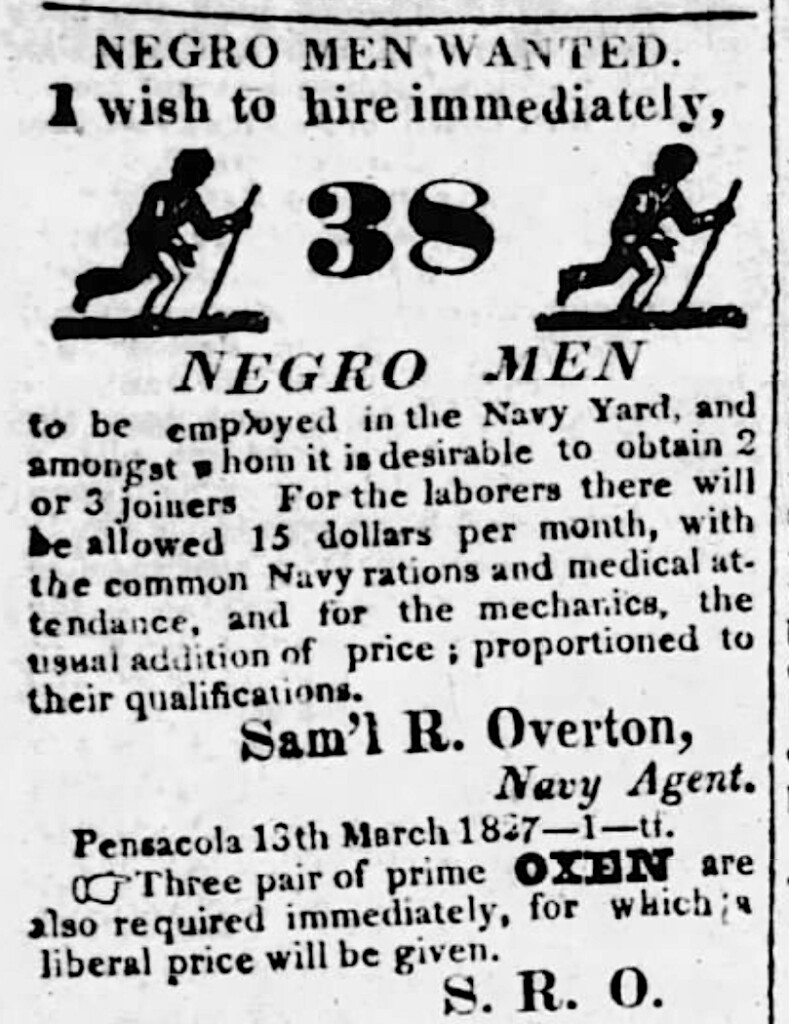

We do have more robust evidence at a select few instillations about the practice of slavery in shipyards, including at the Washington and Pensacola Navy Yards. Another way in which slave labor was employed extensively was in construction. As the country expanded, and thus there was more remote coastline to patrol in places like the Gulf Coast, new fortifications needed to be built where local labor was sparse. The Navy not only hired slave labor from local plantations, they created a market for that labor, and, as Thomas Hulse writes in his study of the Pensacola Navy Yard, the Navy “induced slave ownership because of better than average returns on investment compared to the prevailing returns in the agricultural sector of the Southern economy.”

In urban areas, the political and labor dynamics were different, but the impacts were similar. The federal government in general, and the Washington Navy Yard in particular, were the largest employers of slaves in the District of Columbia, creating a vast slaves-for-hire industry. Many of these slave owners were Navy officers themselves, who profited by collecting the wages of their slaves from the government payroll. The main objection to this practice was not a moral one, but rather a practical and political one. While the Navy Yards played a vital role in national defense, they were perhaps equally important as tools of political patronage. They provided reliable and well-paying jobs, assuming you had the right connections. These jobs delivered reliable votes, and no politician wanted these jobs wasted on people who could not vote. In one of the more brazen examples of this type of corruption, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on a Congressional inquiry in 1859:

“It also came out in evidence yesterday, that at the time of the election in New York last fall, there were packed into the Brooklyn Navy Yard 2,300 mechanics and laborers; that about 1,200 of them were discharged shortly afterward; that at present there were about 1,100 in the yard, and with that number they are now doing more work, and doing it better, than when the yard was crowded with an unwieldly [sic] crew who were not there as mechanics and labormen, but as hireling politicians!”

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 1, 1859

But enslaved people were playing a larger role in the shipbuilding industry. In her study of antebellum shipyards in South Carolina, Lynn Harris writes, “Shipyard slaves were hired initially, later purchased and trained in shipyard skills, rapidly escalating in worth as assets to shipyard production. Shipwrights were well aware of the increasing value of slaves with shipyard skills.”

Perhaps the most famous enslaved person in American history, Frederick Douglass, was hired out by his master to work in shipyards in Baltimore, where he worked alongside ship carpenters. In 1829, he experienced firsthand the growing resentment among whites that blacks were moving into their skilled trades. Even though Douglass was a slave, and just 11 years old at the time, this altercation nearly cost him his life.

“Until a very little while after I went there, white and black ship-carpenters worked side by side, and no one seemed to see any impropriety in it. All hands seemed to be very well satisfied. Many of the black carpenters were freemen. Things seemed to be going on very well. All at once, the white carpenters knocked off, and said they would not work with free colored workmen. Their reason for this, as alleged, was, that if free colored carpenters were encouraged, they would soon take the trade into their own hands, and poor white men would be thrown out of employment. … My fellow-apprentices very soon began to feel it degrading to them to work with me. They began to put on airs, and talk about the ‘niggers’ taking the country, saying we all ought to be killed; and, being encouraged by the journeymen, they commenced making my condition as hard as they could, by hectoring me around, and sometimes striking me.”

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass as American Slave, 1845

The labor of enslaved people had to be circumscribed and monitored, often by violence. These resentments had been present for a long time, and the Navy Department issued a decree in 1817 that banned the use of slave labor in federal Navy Yards, largely in response to the situations in Washington and Norfolk. The regulation, however, was quickly circumvented with waivers, or just outright ignored. While white workers did not want to compete with slaves for jobs, they also liked having slaves on hand to do menial tasks that would otherwise have fallen to them. Managers appreciated slaves as reliable and submissive. And officers liked to profit from the self-dealing of hiring their own slaves to the government.

Slaves at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

For much of the period that we are examining, from the establishment of the Yard in 1801 until complete emancipation in New York in 1827, the records of the Brooklyn Navy Yard do not show a proliferation of slave ownership among the officers, though many did own slaves. Though the decline was slower than in other parts of the state, the slave population of Brooklyn was shrinking, and it does not appear as if the federal government was creating a market for more slave labor. While slaves certainly could have been hired from owners outside the Yard, it does not appear to have been as pernicious as in Washington, Norfolk, or Pensacola.

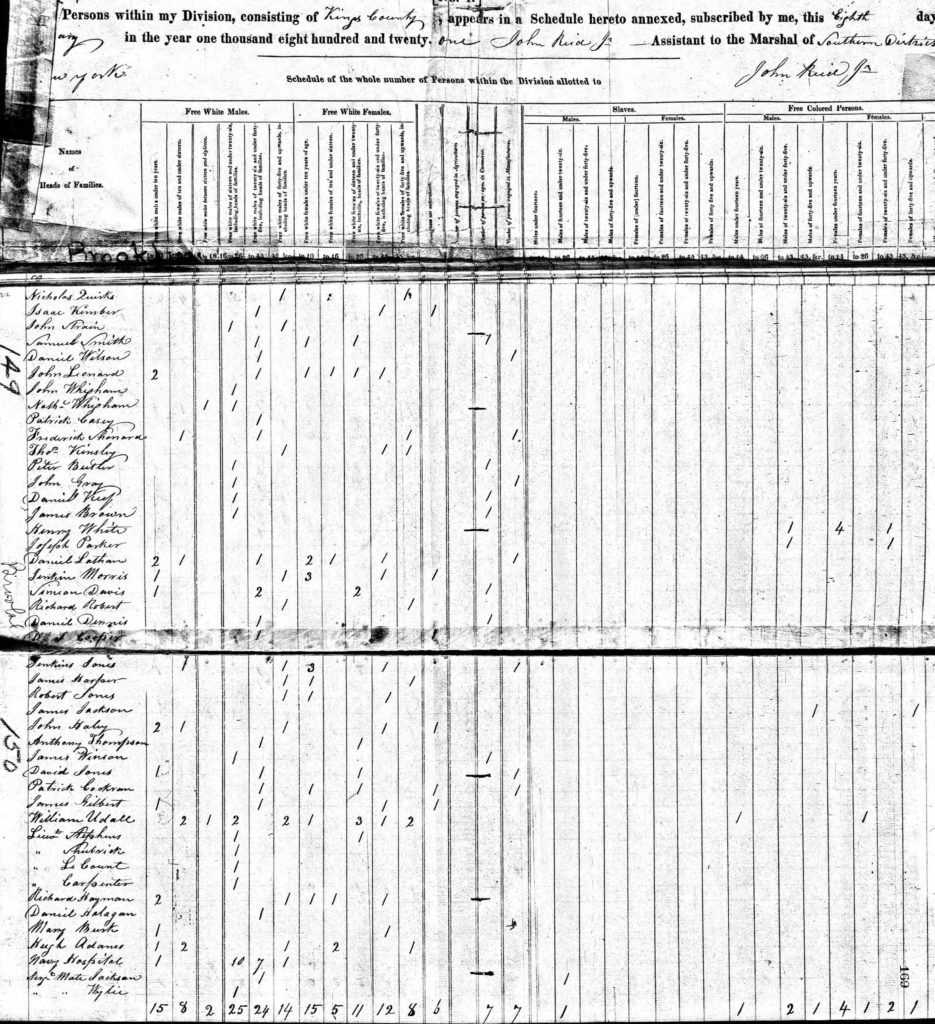

In the 1820 census, the Brooklyn yard had a complement of 474, including resident personnel and their families. Among them is only one enslaved person, belonging to Surgeon’s Mate Samuel Jackson, while Commander Beekman V. Hoffman owned two, though his household was listed in Queens. Chief constructor Henry Eckford is listed as having one colored person in his household, though in 1810 he recorded one slave, so this could be an example of manumission. There are also at least 20 free blacks, and 79 foreign-born. Isaac Chauncey, who was in between stints as Navy Yard commandant in 1820, had one slave in his household in Manhattan.

Chauncey’s ownership of a slave is rather disappointing, as he has earned a reputation as a forceful defender of black sailors. During the War of 1812, when he was in command of forces on the Great Lakes, he scolded Oliver Hazard Perry for complaining that he had too many black sailors under his command. He responded, “I have yet to learn that the Colour of the skin, or cut and trimmings of the coat, can effect [sic] a man’s qualifications or usefulness. I have nearly 50 blacks on board of this Ship, and many of them are amongst my best men.”

A Navy Divided

While slavery may have been abolished in New York in 1827, the Brooklyn Navy Yard remained on the front lines of the issue. It was caught, like the nation, between irreconcilable ideologies and contradictory public policy. New Yorkers could not legally be enslaved, but visitors from other states travelled freely in the state with their slaves, including officers of the Navy. In 1839, a black sailor named William McNally published an explosive account of his time in the naval and merchant service, alleging the widespread use of slaves aboard ships, in clear violation of regulations. Three years later, Secretary of the Navy Abel Parker Upshur was asked to testify to Congress about the prevalence of slaves in the Navy, to which he responded, “There are no slaves in the navy, except only in a few cases, in which officers have been permitted to take their personal servants, instead of employing them from the crew.” It was later revealed that the use of slaves for work far beyond these exceptions was rampant, especially in the Revenue Cutter Service, the precursor to the Coast Guard and then under the jurisdiction of the Navy.

Starting in 1819, the Yard was active in supporting the African Slave Trade Patrols, which were tasked with enforcing the abolition of the importation of slaves to the United States, in force since 1808. These patrosl were largely ineffective; they were under-resourced, subject to shifting political will, and when ships were interdicted, convictions of the perpetrators in US courts were rare. Abolitionists had successfully lobbied for the Africa Squadron, but some pro-slavery southerners saw the potential to direct the Navy to their own purposes.

Though ostensibly believers in states’ rights and limited federal power, there was a small but vocal contingent of southern navalists, among them Upshur and Secretary of State John C. Calhoun. As Matthew J. Karp described in “Slavery and American Sea Power: The Navalist Impulse in the Antebellum South,” “At sea, at least, federal power was not a danger to be feared, but a force to be utilized.” Rather than collaborating with the abolitionist British on slave patrols, they argued, America should expand its forces in order to defend slavery from foreign intervention. The Navy would be the protector of an autarkic slave economy, guarding the sea lanes from the plantations of the Gulf Coast to the manufacturers of New York.

Calhoun and Upshur succeeded in frustrating the expansion of African patrols in the Gulf of Mexico, but ultimately the guns of the Navy turned against the South. In the years leading up to the Civil War, it was impossible to extricate any part of Navy life, or American life in general, from the institution of slavery. Enslaved people were a huge presence in Brooklyn until 1827 – and beyond, thanks to federal law. Every live oak timber, every cotton sail, and even most of the ropes and nails in a Navy ship were touched by the hands of enslaved people. Just blocks from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, warehouses were filled with cotton and refineries were processing sugercane, all produced with enslaved labor. Many of Brooklyn’s formerly slave-owning farmers had moved on to become merchants and bankers, providing transport and credit for their southern counterparts.

After all this, we still do not have a satisfying answer. The official records say no, the labor of slaves was not used to build the great ships of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. But you only need to dig just below the surface to find that those people, who’s names have been lost to history, were very much a part of our history in Brooklyn. Our task now is to continue working to reveal their identities and lived experiences as best we can.