The Brooklyn Army Terminal was designed for war, a massive warehouse and port facility to receive, store, process, and ship war materiel to points around the globe. But the Terminal did not just send out troops and supplies to wage war; it has also been an important place of refuge and relief for people trying to escape persecution, war, and disaster. Here are some examples of the Brooklyn Army Terminal’s history as a safe haven over the last century.

The Children’s Crusade, 1924

Though intended to be used to supply American forces in World War I, the Terminal was not completed until 10 months after the war ended, in September 1919. The war, however, upended the world order, shattered ancient empires, and redrew the map of Europe, which spawned conflicts that dragged on for many years after Armistice Day.

War broke out across the rump of the Ottoman Empire, marked by genocide and ethnic cleansing. Beginning in 1914, Ottoman authorities began the systemic expulsion and slaughter of Armenians and Assyrians within their borders, and this continued well after the war was over and the empire dissolved. In addition, millions of Turks were internally displaced due to Allied invasions, and the crisis was further exacerbated by the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish War in 1919.

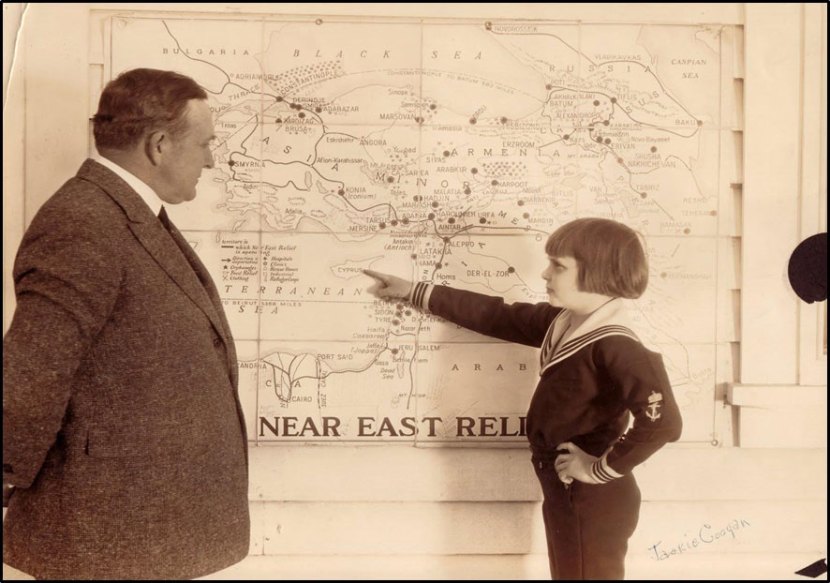

In 1915, the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, later known as Near East Relief, was established in New York to distribute aid to these refugees, including building orphanages and schools. In 1921, 6-year-old motion picture superstar Jackie Coogan decided to lend his money and fame to the cause, donating money and clothes and using his film screenings as relief drives. In 1924, he crisscrossed the country for five months raising money and awareness about the plight of refugees. This “children’s crusade” culminated in a massive rally in Prospect Park’s Nethermead on August 16, where 40,000 children and their parents gathered to see the movie star and collect more relief supplies.

Meanwhile, all of these supplies were being gathered in the Brooklyn Army Terminal – in total, more than $1 million worth (about $14.5 million today) were delivered to the Mediterranean on several different relief ships. Coogan himself followed them; on September 6, he boarded the ocean liner Leviathan and made stops in Paris, London, Rome, and Athens, where he visited an orphanage and was named Officer of the Order of George by the Greek provisional government.

Aid to Puerto Rico After Hurricane San Felipe Segundo, 1928

On September 13, 1928, the San Felipe Segundo hurricane hit Puerto Rico, the most destructive storm in the island’s history until last year’s devastating Hurricane Maria. It killed 312 people directly, left more than half a million people homeless, and destroyed the island’s coffee industry.

Meanwhile in Brooklyn, a 4-million-square-foot warehouse was stocked to the ceiling with surplus supplies from World War I, and it was immediately mobilized to deliver relief to Puerto Rico. Just four days later, the Navy transport Bridge was moved from the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the Terminal and loaded with supplies. It departed just two days later, arriving in San Juan on September 24, carrying:

- 1 million Army field rations

- 2 Army field hospitals, each with 1,000 beds

- 3,600 blankets

- 5,000 cots

- 2,000 tents

- 1,100 garments from the Red Cross

Bringing Soldiers Home, 1945–51

During World War II, 3.2 million American soldiers were dispatched from the New York Port of Embarkation, which encompassed all of the Army port facilities across the region, and roughly 600,000 of them departed from the Brooklyn Army Terminal. Nearly 5 million then returned home through New York, making it both the largest embarkation and debarkation point in the nation. The Terminal was set up to be a joyous reception, with bands playing to greet returning ships, and the piers and warehouses along the Narrows were painted with signs reading “Welcome Home.”

But not all of those soldiers came back alive, and the Terminal had an important and solemn duty receiving the remains of those killed in the Western theaters. World War I was the first overseas conflict in which large numbers of American dead were repatriated, and in World War II, the American Graves Registration Service was established to identify and repatriate American remains. Of the 400,000+ Americans killed in the war, the service was able identify and secure the remains of approximately 281,000 (most of the remainder were lost at sea), and the families of 180,000 requested that their bodies be brought back to the US. Of this total, more than 140,000 were shipped through the Brooklyn Army Terminal.

The first ship carrying war dead from Europe was the Joseph V. Connolly, which arrived on October 26, 1947 with 6,251 aboard, about one-quarter of them Brooklynites. In preparation for their arrival, the Graves Registration Service established office and storage space on the 3rd Floor of Buildings A and B, a rostrum for memorial ceremonies on one of the piers, and temporary barracks to house the soldiers that would escort the remains to the cemeteries. Families had the right to have the remains delivered wherever they chose, either in National Cemeteries or in private plots. Once the caskets arrived, they would be loaded onto special mortuary trains that were dispatched across the country. This process was a major part of operations at the Terminal from 1947 until the last large shipments arrived in 1951.

Survivors of the Andrea Doria Sinking, 1956

On July 25, 1956, the ocean liner SS Andrea Doria collided with the MS Stockholm off the coast of Nantucket while en route to New York from Genoa, Italy. The collision sheared off the bow of the Stockholm, and punctured a hole in the starboard side of the Andrea Doria that extended 40 feet below the waterline. 11 hours later, the Andrea Doria sank, taking 46 people with her, and leaving 1,660 passengers and crew without a ship.

Many ships rushed to the aid of the stricken liner, including the US Navy troop transport USNS Pvt. William H. Thomas, which was en route to New York from Bremerhaven, Germany. It picked up 156 of the survivors, while the destroyer escort USS Edward R. Allen delivered 77 crew members, including Capt. Piero Calamai. The remainder were mostly picked up by the fruit carrier Cape Ann, the liner Ile de France, and the Stockholm itself, which delivered their passengers to Manhattan’s West Side piers.

Incidentally, while the Stockholm made its first port call in Manhattan, the stricken ship was eventually towed to Sunset Park, just seven blocks from the Brooklyn Army Terminal, to be repaired at the Bethlehem Steel shipyard on 51st St. The repair work to replace the 75-foot section of the bow took nearly four months, at a cost of $995,000, but the Stockholm was back in service by November (and it’s still in service today).

Refugees from the Hungarian Revolution, 1957

In October 1956, Hungarians launched an armed revolt against the communist government and Soviet occupation, prompting a swift and brutal response from Moscow. As a result, more than 200,000 Hungarians fled their homeland, and many of those refugees eventually found a home in the United States.

The US was already a safe haven for people escaping from behind the Iron Curtain, as the 1953 Refugee Relief Act permitted the entry of 209,000 refugees from countries facing communist oppression. On November 9, 1956, with the violence in Hungary raging, President Eisenhower directed that the remaining 6,500 visas for Eastern Bloc citizens be granted exclusively to Hungarians, and issued an additional 15,000 provisional visas. This number would soon prove inadequate. Within a week, the federal government began making preparations for the refugees’ arrival, reactivating the World War II staging area Camp Kilmer in New Brunswick, NJ. Shortly thereafter, the first Hungarians began to arrive, and by the end of the year, there were already 15,000 in the camp.

Ships took longer to organize, and the first to arrive under this refugee program was the Army transport Leroy Eltinge, which arrived in New York on January 1, 1957. The ship had departed Bremerhaven with 1,746 Hungarian passengers, but arrived in New York with 1,747 aboard – a baby was born early on the morning of New Year’s Day while the ship was docked in the harbor undergoing a medical inspection. The parents, Henrik and Gabrielle Matusek, named the boy Eltinge, after the ship that delivered them to freedom.

The final boatlift of Hungarians arrived in Manhattan on April 30, 1957, and Camp Kilmer was closed the following day. Refugees continued to arrive at a rate of 700-800 per month, and Brooklyn Heights’ Hotel St. George was made the official refugee reception site. In total, more than 38,000 Hungarians were resettled in the United States, and more than 5,400 of them first set foot in the United States at the Brooklyn Army Terminal.

September 11 Boatlift, 2001

While these rescues were notable, they all paled in comparative size to the efforts undertaken to evacuate people from Lower Manhattan following the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. With all bridges and tunnels cut off, and fires and debris making it hard for people to move north, many were stranded on the southern tip of the island. The Coast Guard put out a call to all vessels to respond, and hundreds of boats of every description – tugboats, ferries, fishing boats, private yachts – began to arrive. With so much traffic in the harbor, boats dropped off evacuees wherever there was space. Since the Brooklyn Army Terminal boats one of the largest working piers in the city, it was an important docking point for large ships, including the Staten Island Ferry and New York Waterways ferries. In total, an estimated 500,000 people were evacuated by water, making it the largest boatlift in history.

The Army Terminal continues to be an important location for emergency services, as it is home to one of the NYPD Harbor Units, Harbor Charlie, and it has served as an emergency response center during events like Superstorm Sandy in 2012.